Playing Along with Rules As Code: Part 6

So in the last post we got to the point where our model of the law understands what it needs to understand in order to be able to generate “Year of Employment” objects. In this post, we’re going to finish our rules, we’re going to generate an interview, and use it to debug problems in the law.

Fudging It (a little)

I spent some time trying to get OPM to play nice, but ran into a number of brick walls. So for the sake of getting on with thing’s we’re going to fudge it, and manually enter in a list of Years of Employment. We will only need to provide three pieces of information for each, the date on which it starts (either the employment start date or the designated year start date or the anniversary of either of those), which Year of Employment follows the current one, and the wages that the employee earned in that year.

We’re also going to drop the calculation of whether the year of employment is interrupted and the calculation of whether it lasted a year from the temporal values attached to the employment, and instead calculate those values as true or false values on the Year of Employment Object.

Setting Up Our Year of Employment Rules

Here’s what the rules look like:

Year of Employment is interrupted if

YearDifference(

Year of Employment,

for(

next yoe,

Year of Employment)) <1

Year of Employment Employed For Twelve Months if

IntervalAlways(

Year of Employment,

for(

next yoe,

Year of Employment),

for(

parent employment,

employment employee employed by this employer))

and

MonthDifference(

Year of Employment,

for(

next yoe,

Year of Employment)) = 12

The first says that the year of employment was interrupted if the difference, in years, between the date on which that year of employment began and the date on which the next year of employment began is less than one.

The second says that the employee was employed for twelve months (as of the end of the year of employment) if at all times between the start of this year of employment and the start of the next year of employment the temporal value for employed by this employer in the same industrial establishment is true; and, the difference in months between those two dates is 12.

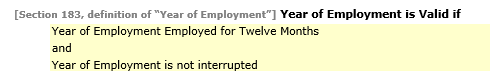

We can now use those two factors, plus the dates that we are manually entering (though we are also calculating them… grrr) to determine which are valid years of employment. The rule for that looks like this:

Year of Employment is Valid if

Year of Employment Employed for Twelve Months

and

Year of Employment is not interrupted

Calculating Employment Duration Anywhere

So before we needed to know how long a person had been employed in the same location, in order to determine whether they had been employed in that location for a 12-month period. Now, in order to calculate their vacation entitlement, we need to know how long they have been employed by the same employer, regardless of where. So we’re going to create another couple of temporal variables to answer that question in much the same way, except we no longer care whether the industrial establishments match. Here’s what the new rules look like:

Employment (other_employment) is a member of relevant employment anywhere if

instanceequals(

other_employment employer,

employment employer)

and

instanceequals(

other_employment employee,

employment employee)

Employment Employee Employed By This Employer Anywhere = TemporalFromRange(relevant employment anywhere, employment start date, employment end date allowing for unknown, True)

Employment Duration Anywhere Start Date = WhenLast(the current date, uncertain(Employment Employee Employed By This Employer Anywhere))

Employment Duration Anywhere = TemporalYearsSince(Employment Duration Anywhere Start Date, the current date)

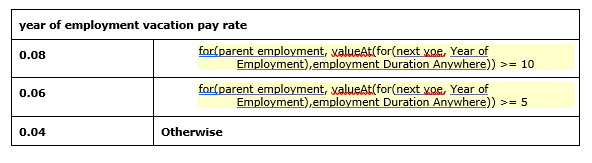

Now we have an “Employment Duration Anywhere” attribute that we can use to calculate vacation entitlement as of the end of a year of employment. So to do that, we are going to rewrite our table for calculating vacation rates:

The conditions now read “if, with regard to the employment for the current year of employment, the value of the employment duration value anywhere as of the start date of the following year of employment is greater than or equal to 10 (or 5)”.

Recalculating Vacation Pay

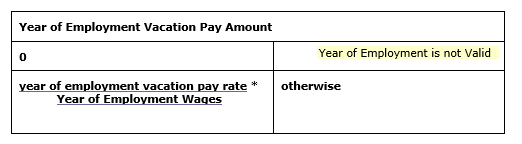

Now previously we had defined the vacation pay amount as a multiple of the wages by the pay rate. But we want the vacation pay amount for invalid years of employment to be zero. So we will rewrite that rule as a table that looks like this:

Using The Encoded Rules To Build Something Cool

OPM will automatically generate an interview that is capable of answering the question of how much vacation pay was owed in each year of employment with regard to a particular employee. So I’m going to take the generic interview, and I’m going to add a single line to a label on the final screen that will display for each Year of Employment in the tool.

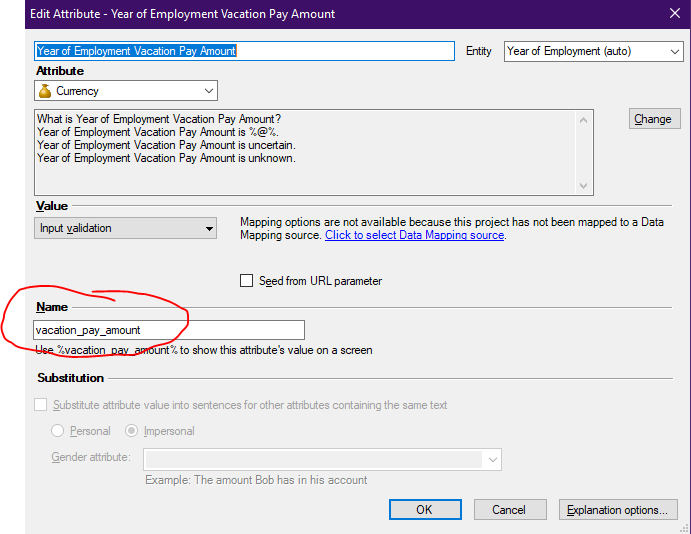

The vacation pay owing for the year starting on %Year_of_Employment% is %vacation_pay_amount%.

I have defined “vacation_pay_amount” as the name that I can use to display that value inside the Data screen, like this:

Now I hit the Debug button, and it loads the default interview.

The default interview is going to ask for things in strange ways, and in strange orders, but if the rules are working properly, it should ask for what it needs in order to answer the question. Let’s see what we get.

The Interview

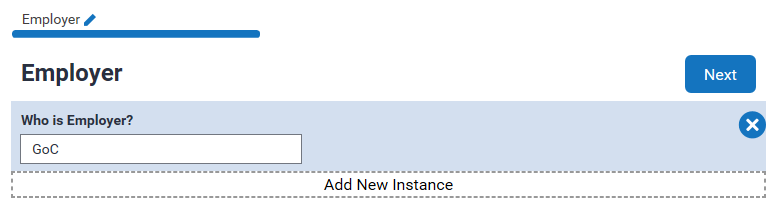

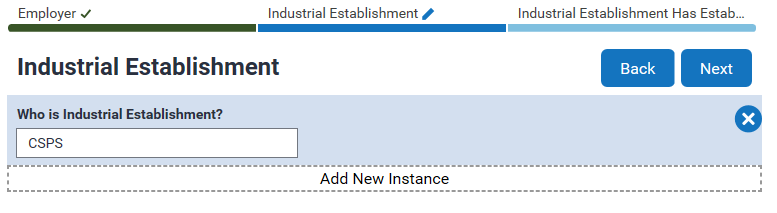

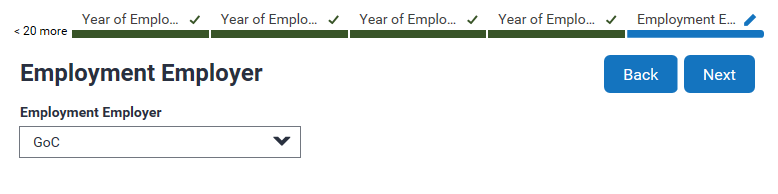

First it asks for an employer, so I give it “GoC”.

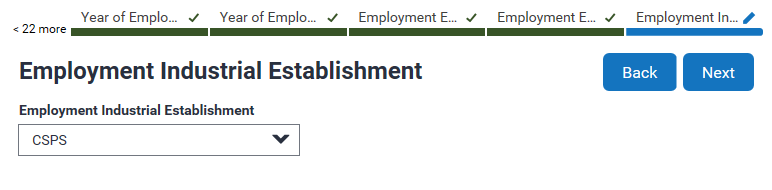

You can see that you can add more than one employer to the tool. I click “Next” and it asks me about industrial establishments. We will pretend that Canada School of Public Service is the industrial establishment we are interested in, here.

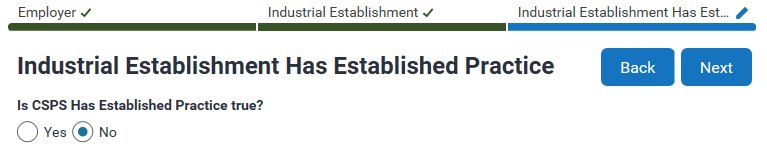

By default the interview asks for everything that it can, so if there is an industrial establishment, that establishment might have an established practice for when to pay vacation pay. It asks.

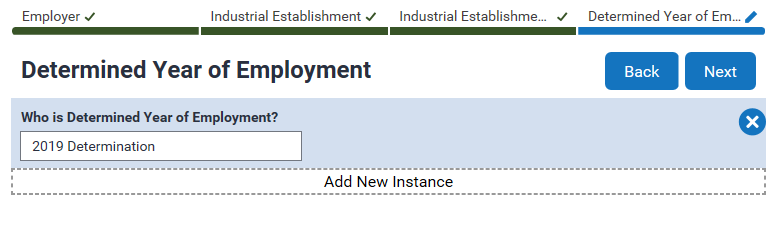

I haven’t told it what variables aren’t required, so it treats everything as thought it was mandatory. For now we will patronize the interview and give it an answer for each question. Now it wants to know if there are any determined years of employment for CSPS.

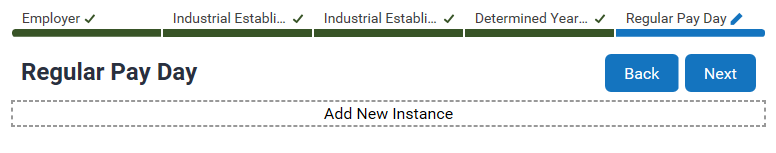

We create one called 2019 Determination. It then asks for regular pay days, but we’re not doing anything with that, yet, so I’ll leave it blank.

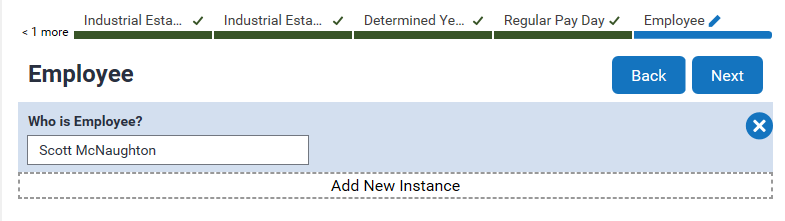

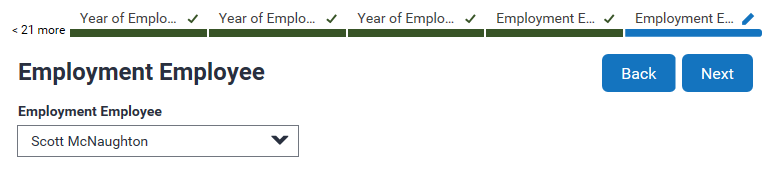

Next it asks about Employees. We will tell it about Scott McNaughton.

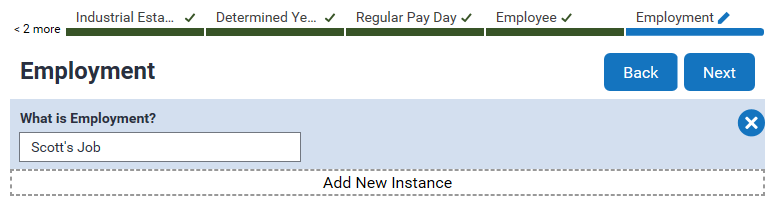

Next it wants to know about an employment object. We will create one called “Scott’s Job”.

Next it asks about vacation periods, but again, we don’t care.

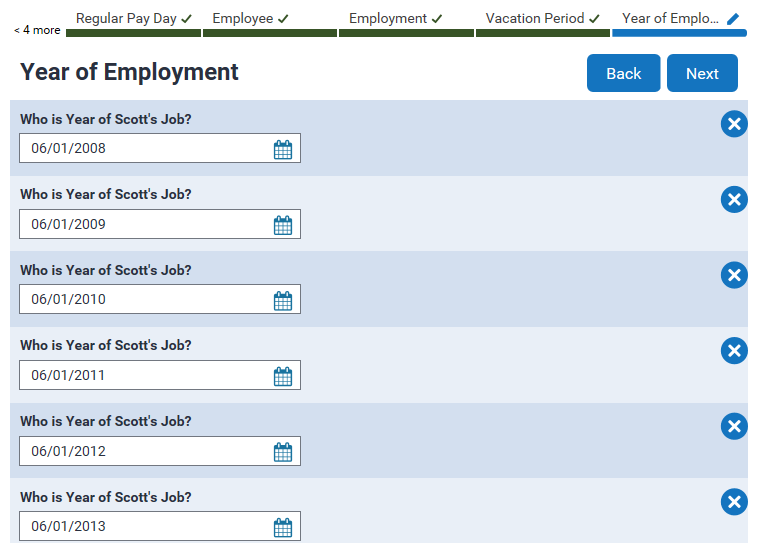

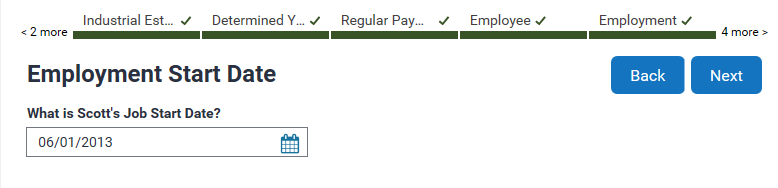

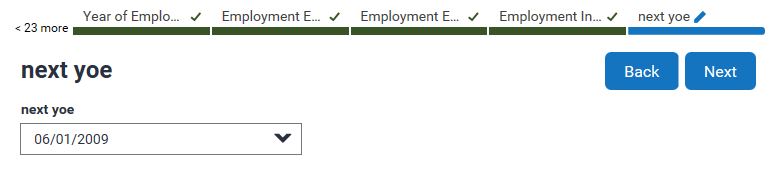

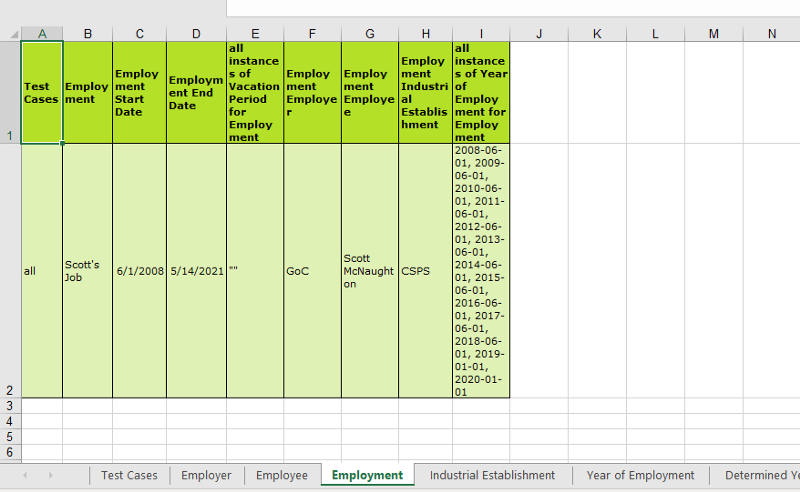

Next it asks about the Years of Employment for Scott’s Job. Here’s where we have to do some manual data entry. To test our calculations for vacation pay, we’re going to pretend that Scott has been employed at CSPS since June of 2008. And we’re going to say that CSPS created a determined year of employment effective January of 2019. So we enter in all the dates on which those years of employment would start.

At this point the interview gives us an error that something is missing. This is because it would have asked about the start and end dates for Scott’s Job immediately after we told it about Scott’s Job, except it didn’t yet have anything to do with them. Once we give it a bunch of years of employment, it needs to know what the start date is to calculate various things. This is just another of the many problems you would be able to fix by actually designing the interview instead of allowing OPM to generate it automatically. So we click on the screen for Employment Start Date and start from there.

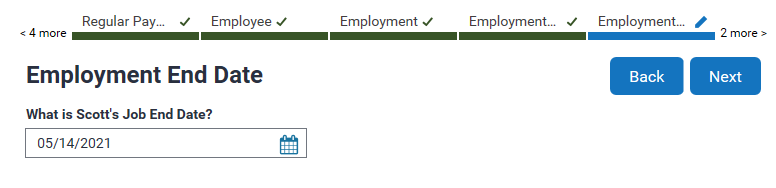

It then asks for the end date of the employment, and because it will complain if we don’t, we just make one up in the future.

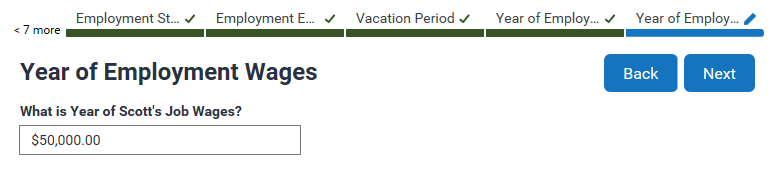

We go back through Vacation Period and Years of Employment, which we have already done, and when we click forward the error is gone and we are asked for Scott’s Wages in each year of employment. We’re going to throw $50,000 in there for each year. (Give Scott a raise, you guys.)

It then asks for the employer, the employee, and the industrial establishment for “Scott’s Job”.

It then needs us to link each year of employment to the next one manually. This would be done automatically if I could get OPM to play nice, but whatever.

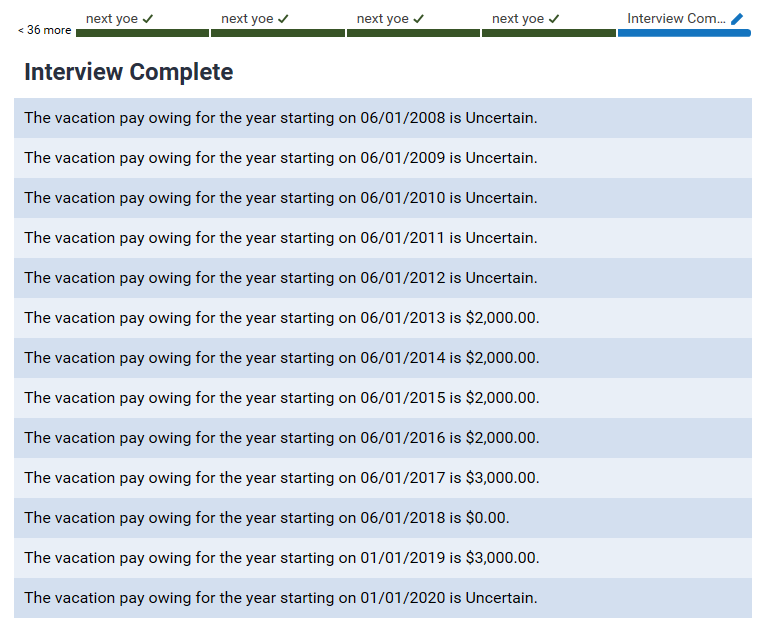

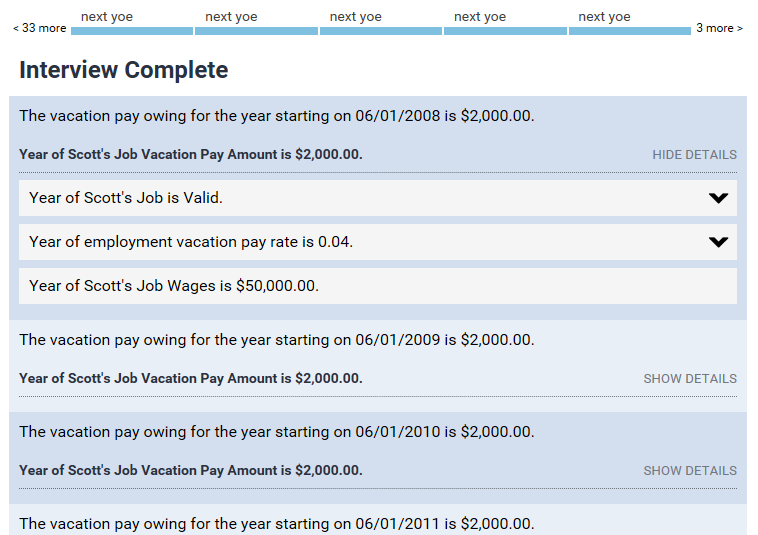

And that’s it, and we get to the last screen of the interview.

Wait… that’s not right. Why are the first years uncertain?

Oh. I said his employment started in 2013 instead of saying it started in 2008, so the “has he been employed here for the last 12 months” part is failing for those years. I’ll fix it on the “Employment Start Date” screen, and come back.

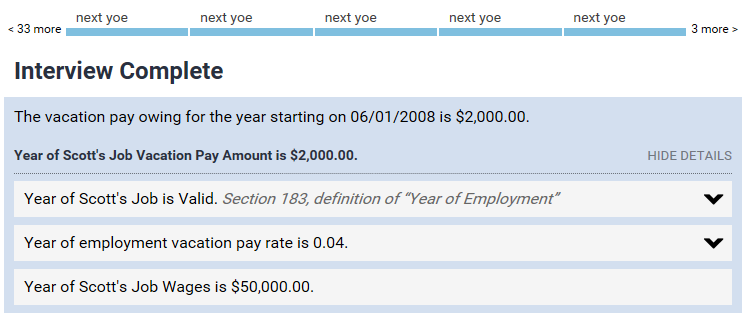

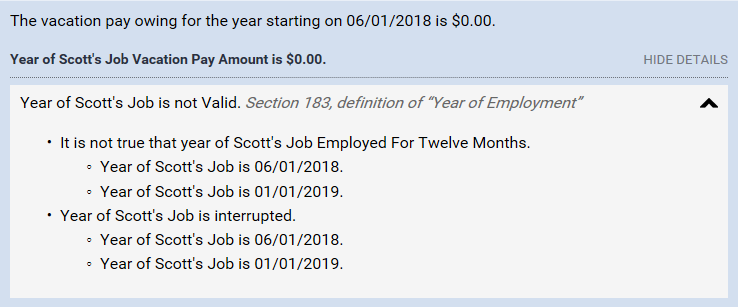

There you have it. The rules are showing that Scott’s vacation pay for the first 4 years is $2,000 (4% of $50,000), starting at the end of year 5 it’s $3,000 (6% of $50,000), and starting at the end of year 10 it’s $4,000 (8% of $50,000), except for the year of employment starting on June 1, 2018, which is invalid (because during that “year of employment” he did not work 12 months). And the vacation pay for the current year of employment is uncertain, because we don’t yet know when it will terminate. A new determined year of employment could be set between now and December 31.

Creating Test Cases

One of the nice features about OPM is that it allows you to save the data that you enter in a debug interview as a “test case” which is saved in an Excel file.

Once page of the excel file for the data I just entered looks like this:

It is very easy to use this excel file to add test cases, and then select any of them that you want to get its conclusions. You can also use your Excel-fu to randomly generate test scenarios in order to give your application possibilities you hadn’t personally considered.

Explaining Answers

An important features of OPM is the ability to generate explanations for the answers that it gives. If I go back into the default interview and add a single control, the explanation for the year of employment vacation pay amount attribute, to the screen, here is what you get:

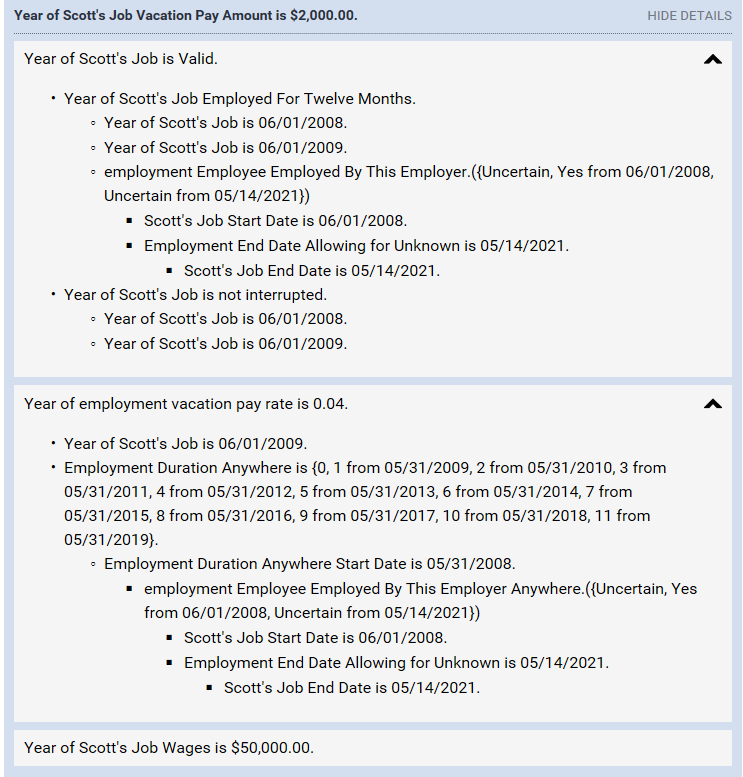

I have clicked on “show details” for the first year of employment above. You can see that because OPM knows it is using the validity of the year of employment, the pay rate, and the wages to determine the pay amount, it has shown those three variables. Factors with sub-factors are available in a drop down. If I expand both of them, this is what you see:

It’s clearly not going to win any awards for poetry. But remember: this is what you get with zero additional effort on top of writing the rules. The explanations can be considerably improved.

And it is possible to include annotations for source rules. If I go into Microsoft Word and add a reference tag to the rule like this:

Then the explanation changes to look like this:

Now let’s say I’m curious why Scott’s vacation pay in the section half of 2018 is $0. I can scroll down and take a look:

Again, there’s a lot we could do to improve how that explanation is presented, but it is enough to point you in the right direction as it is.

The Important Thing

This is the part that I worry is going to get lost by virtue of the fact that this is a series of blog posts, and not a video. Drafting the rules and getting them to work properly took several hours. That’s partly because they are complicated, and required the use of some advanced features. It’s also partly because I haven’t actively used OPM in three years, so I’m relearning some things as I go.

But once that was done, generating a web interview that could collect the information required to answer complicated legal questions and provide explanations for those answers that refer to the source law took approximately 3 minutes.

Honestly. Here’s what I had to do:

- Add a label to the vacation pay amount attribute so I could include it in a label.

- Create a section on the interface screen for each year of employment.

- Add a label to that section with the required text.

- Add an explanation to that section for the attribute’s value.

That is the most important thing. If you do the work up front with the rules, application development is just crazy easier.

What are These Sections Doing Wrong?

One of the interesting questions is “if we had been using Rules as Code while writing these sections of law and regulation, how might we have ended up doing it differently?”

If I was the coder-lawyer in the room, here’s what I would have said:

What we are interested in how much is owed, and when. We have decided on annual periods, which is fine, but we have also given them the ability to modify when the annual period happens. That will create sub-annual periods of time. So we don’t want to define “year of employment”. We want to define “period of employment,” which is a year long by default, but can be any length equal to or less than a year. Whatever the length of a period of employment, if you worked a part of it, you are entitled to vacation pay for one year, prorated for the amount of time that you actually worked in that period of employment, regardless of how long it was.

What Have We Learned?

We’ve covered a lot of territory in the last 6 posts. Here are the big takeaways:

- Encoding “normal” rules sucks.

- Encoding rules while drafting them will reveal some problems that you might not otherwise have noticed, and can reveal more problems you don’t notice while drafting.

- If someone else is encoding the rules, application development becomes crazy easy. And so, potentially, does compliance.

- The tools available are cool, but none of them are perfect.

- Encoding laws doesn’t need to look like you’re a character in the Matrix.

All of which falls under one or both of two bigger points:

- Rules as code has the power to improve the laws, if we do it while we are drafting the rules.

- Rules as code has the power to simplify service delivery and compliance, and more-so if we do it while we are drafting the rules.

What’s Next? Not much.

I could still add features to be able to calculate when the vacation pay is due, but frankly, I’m sort of OPA’d out. So that’s probably not going to happen. But let me know if there’s something specific you’d like to see.

The OPM software is available for free for educational purposes from Oracle, and I would be happy to provide the project file to anyone interested in trying it. Just hit me up on twitter at @RoundTableLaw.

Thanks for following along, and thanks to the great people in the Government of Canada who are pushing us into the future with this work. I hope these posts have contributed somewhat.