Playing Along with Rules as Code: Part 5

Continuing our work encoding section 183 of the Act in Oracle Policy Modelling. Oh, man. Ok, let’s get into this.

This is the fifth in a series of posts following along with the Government of Canada’s Rules as Code project. Check out the earlier posts for context.

The Next Part of the Problem

Let’s start with a reprint of the section we’re encoding, section 183’s definition of “year of employment.”

183 In this Division,

…

year of employment means continuous employment of an employee by one employer

(a) for a period of twelve consecutive months beginning with the date the employment began or any subsequent anniversary date thereafter, or

(b) for a calendar year or other year determined by the employer, in accordance with the regulations, in relation to an industrial establishment. (année de service)

Last time we got to the point where we could take the combination of information about an employment and information about designated years of employment from an industrial establishment, and combine them into a single temporal variable that can be used to get the start dates for a “year of employment.”

Start dates are great. But now we have to figure out what to do with them, and step #1 is going to be statutory interpretation. And this one is a doozy.

Bob Gets a Job

Let’s get at the statutory interpretation problem here in the context of an example.

Bob is a person who is employed by an employer on January 1, 2019. At that time, the industrial establishment in which he was employed did not have a designated year of employment. Then, his employer designated a year of employment for that industrial establishment, effective June 1, 2019, that starts on June 1 of each year, and ends on May 31 of the following year.

Here’s the question I want to answer: What is Bob’s first “year of employment?”

Bob was continuously employed by one employer, so that part is dealt with. Subsection (a) says “for a period of twelve consecutive months beginning with the date the employment began or any subsequent anniversary date thereafter.” Taking that at it’s word, one plausible answer to the question is January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019 is the first “year of employment.”

Then in (b) it says “ for a calendar year or other year determined by the employer”. As of June 1, 2019, the employer determined that the year would run from June to May. So June 1, 2019 to May 31, 2020 is also a potential valid answer for a “year of employment.”

The two subsections are divided with an “or”. Again, the way that subsections like this work is that you should be able to attach the introduction to each of them, and then put or in the middle of the two bigger statements. So if we reformulate, the section says a calendar year is:

a period of continuous employment with the same employer for 12 months starting with the date they start, or

a period of continuous employment with the same employer for a year set out by the employer

So we know from context that the year of employment is used as the unit for which vacation entitlements are calculated. And we know from common sense that the government is not trying to set up a system where people can be entitled to the same thing twice because of some paperwork thing. So we can conclude from that that the government did not mean for it to be possible for one year of employment to overlap another with regard to the same employment. If it did, people could get twice as much vacation for a period of time.

So we’re going to go with the assumption that years of employment are not overlapping with regard to the same employment.

Does that help us answer the question? Only slightly. We have the possibility that the first answer is correct, and the possibility that the second answer is correct. The rule against overlapping just means that they can’t both be correct at the same time, because then Bob would have two years of employment for the second half of 2019.

But if the first one is right, we are violating the rule in subsection (b) as of June of 2019, because we are not paying attention to the designated year.

And if the second one is right, Bob doesn’t have a “year of employment” for the first six months.

We can assume that the law did not intend to allow the employer to effectively nullify vacation entitlements by changing the designated year. From context, the legislation is designed to protect employees, not provide loopholes with which to screw them over. So let’s reject the idea that only the second one is correct.

But if we rely on only the first one being true, then from January to June of 2020 Bob doesn’t have a year of employment, either.

Wait… didn’t the regulation say something about vacation for periods of less than 12 months?

13 (1) Where an employer has determined a year of employment under paragraph (b) of the definition year of employment in section 183 of the Act, the employer shall, within ten months after the commencement date or after each subsequent anniversary date, as the case may be, of the determined year of employment, grant a vacation with vacation pay to each employee who has completed less than 12 months of continuous employment at that date.

Oh! OK, so section 13(1) exists to help solve this problem! Great. But wait… can a regulation grant vacation rights that aren’t granted in the Act?

184 Except as otherwise provided by or under this Division_, in respect of every year of employment by an employer, every employee is entitled to and shall be granted a vacation with vacation pay of_

You know what? Let’s go with “otherwise provided under this Division” including things provided in the regulation, shall we? Sounds good.

OK. So now we know that section 13 of the Regulation is specifically designed to require employers to grant vacation for less than a full year of employment when a year is designated. Let’s see if section 13 solves the problem for Bob.

13 (1) Where an employer has determined a year of employment under paragraph (b) of the definition year of employment in section 183 of the Act, the employer shall, within ten months after the commencement date or after each subsequent anniversary date, as the case may be, of the determined year of employment, grant a vacation with vacation pay to each employee who has completed less than 12 months of continuous employment at that date.

So… “where an employer has determined a year of employment”. So “where” here probably means “if”. And “has determined a year of employment” probably means that they have done so, and a determined year of employment is still in effect. Otherwise, we have a situation where ever having designated a year of employment changes the way that vacation is calculated for people who arrive after it is removed, which would seem strange.

So “if there is a designated year of employment in effect”, the employers has to give vacation (we’ll come back to that part) to “each employee who has completed less than 12 months of continuous employment at that date_”._

Yikes. Completed less than 12 months of continuous employment between when and what date?

Context time.

(2) The vacation granted to an employee pursuant to subsection (1) shall be the number of weeks of the employee’s vacation entitlement under section 184 of the Act divided by 12 and multiplied by the number of completed months of employment from and including

(a) the date employment began, for an employee who became an employee after the commencement date of the year of employment referred to in subsection (1); or

(b) the commencement date of the year of employment previously in effect, for all other employees.

OK, so here it tells us that what we’re trying to do is calculate vacation entitlement as a proportion of the entitlement that would exist if the person had just finished the whole year in the normal way. So we’re talking about people who completed less than 12 months of continuous employment during the employment year that ended on the most recent anniversary date? It’s a guess. It could be wrong, but let’s try it.

And subsections (a) and (b) set out that we are talking about (a) people who were hired after the start of the “year of employment previously in effect” (Yay! Our last guess was right!), and everybody else. For the first category, count from when they started for as long as their employment was continuous. For the second category, count from the start of the year of employment.

So it seems like what we’re talking about here is the portion of the previous year of employment for which the person was employed, whether there employed overlapped with the start and ended early, or it overlapped with the end and started late.

So using that context, let’s say that “each employee who has completed less than 12 months of continuous employment at that date” in subsection (1) means people who have completed less than 12 months of continuous employment in the year of employment previously in effect as of the end of that year of employment.

OK. Now we can go back to figuring out whether it helps Bob.

When the company implements a year of employment as of June 1, 2019, the company is obliged to pay pro-rated vacation to people who have completed less than 12 months of continuous employment in the year of employment previously in effect (we think).

What is the year of employment previously in effect for Bob as of June 1, 2019?

If we had asked what the year of employment start and end date were in March of 2019, for example, we would have said “January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2019”. That is a 12-month period, it just wasn’t finished.

But in order to be a “year of employment” it needs to be employment for 12 months starting on a hire or anniversary date, not overlapping with another period.

This is a dead end. We can’t come up with an interpretation of what the rules actually say that will get Bob vacation entitlements for those first 6 months. What should we do? Add rules, or leave Bob to his doom?

Rules as Code, or Software Development?

Now we need to talk about the purpose of a Rules as Code experiment. Is the purpose of the project to generate a tool that calculates vacation pay? If so, we have to make it up as best we can. We encode our practices, not the rules.

But the point of Rules as Code is not merely that it is a means of automating what a law says. The point of Rules as Code is that if you think, while you are drafting the law, about how a computer would represent it, you will create laws that have fewer problems and can be implemented without having to make things up.

So in a world where Rules as Code is the norm, attempting to encode the rule as you go would give you the opportunity to discover the problem.

Well, point proved. We are trying to encode the rule, and we discovered the problem. I certainly didn’t know it was there before going through this exercise. So Rules as Code can do that, for sure.

But this whole conversation has been about Bob.What if Bob had never entered into the head of the drafters? We might have gone through the whole process of encoding these rules without noticing the strange results for Bob. In theory, Rules as Code would still make it easier to discover that problem automatically later, because automated rules are also testable.

Whether that is true — that encoding laws as you draft them gives you the opportunity to automatically detect problems with the law itself — is one of the features that Rules as Code claims to have.

So we have a choice, here. We can do software development, and encode our best practices. Or, we can do a Rules as Code experiment, and encode a reasonable interpretation of what the rules actually say, and then see whether or not the problem with Bob can be made visible after the fact.

Software development is boring. Let’s do a Rules As Code experiment. So let’s encode the legislation in as close as we can to its current meaning, and then see whether or not we can use the encoding to learn that we have made a mistake.

Back to Years of Employment

OK, so we are back to year of employment. A year of employment is a period of continuous employment of 12 months starting either on the hiring date or its anniverary if there is no designated start, or on the start or it’s anniversary if there is. And, years of employment may not overlap.

So we can say that a year of employment exists if:

- there is a relevant anniversary or start date

- the person is continuously employed during that period

- there are no other relevant start dates during that period

The first thing to to do is to take our temporal value that gives us start dates, and turn it into a list of start and anniversary dates that we might be able to use to find years of employment.

First Up: Anniversary Dates

A valid start date for a year of employment exists if it is one of the start dates, or if it is an anniversary of one of the most recent start date. So we are going to use the if function again. This is going to get complicated, so we’ll go step by step.

Employment Temporal Anniversary Value = if(

condition,

value if condition is true,

value if condition is false)

So the condition here is whether the current value is less than a year ago, in which case the “true” value will be whatever the current value is. OPM provides a function called “temporalYearsSince” that we can use to calculate the difference between two dates in years, and we can check to see if that is less than 1.

Employment Temporal Anniversary Value = if(

temporalYearsSince(

Employment Effective Anniversary Date for Calculating Vacation Pay,

the current date) < 1),

Employment Effective Anniversary Date for Calculating Vacation Pay,

false value)

Note that when you are dealing with a temporal value, the variable “the current date” doesn’t need to be specified, and refers to the date used for figuring out the value of the temporal value. So it is not the current date as of the time of writing the rule. It is the date for which a value is requested.

It sort of makes sense if you squint and turn your head to the side a bit.

Now we need to define what the value should change to if the current value is more than a year ago. We don’t know that it is ONLY one year ago, it could be three years ago… so we need to define it in a way that will be correct no matter the time period being asked about.

OPM provides a helpful function called “NextDate” which takes a date as a starting point, and then a day of the month and a day, and will tell you when the next occurance of that date is. Because our condition specifies that we don’t recalculate until the current date is more than a year after the most recent value, we need to choose a date in the past, and then find the next anniversary of the current value. So if we choose a date one year in the past of the date for which the anniversary is being calculated, and find the next anniversary after that date, that should give us what we want.

OPM provides a very natural language way of subtracting dates, so we can say “the date one year before x”. It also gives us “extractday()” and “extractmonth()” functions that we can use to get the day of the month and the month of the year from an existing value. So we can say “the next anniversary of the current value after one year ago from now” like this:

nextdate(

the date 1 year before the current date,

extractday(Employment Effective Anniversary Date for Calculating Vacation Pay),

extractmonth(Employment Effective Anniversary Date for Calculating Vacation Pay))

We can make that the false value of our rule above, and our rule reads like this:

Employment Temporal Anniversary Value =

if(

temporalyearssince(Employment Effective Anniversary Date for Calculating Vacation Pay, the current date) < 1,

Employment Effective Anniversary Date for Calculating Vacation Pay,

nextdate(

the date 1 year before the current date,

extractday(Employment Effective Anniversary Date for Calculating Vacation Pay),

extractmonth(Employment Effective Anniversary Date for Calculating Vacation Pay)))

Phew.

So what that says, in English is basically (if the current most recent start date is less than a year ago, the value is the most recent start date. Otherwise, the value is the next date with the same day and month after a day one year prior to the date on which you are asking.)

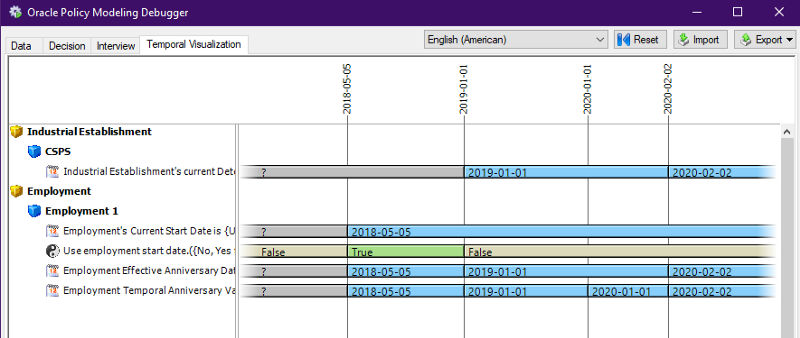

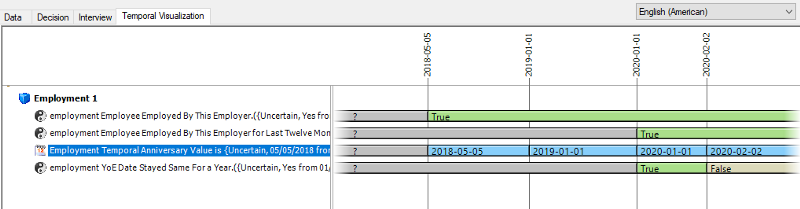

OK, let’s take a look at the temporal visualization and see if it’s working so far.

And we can see that our new variable switched from 2019–01–01 to 2020–01–01 on that anniversary date, and then switched again when it was set by the employer on 2020–02–02. Perfect.

Continuous Employment

So now we know what the start dates are. Now we need to be able to figure out where, and for how long, a person was continuously employed. We could model that as a temporal value for most recent employer on the employee object, but in our model we contemplate that a person might be employed in more than one place at the same time, so “most recent employer for the employee” is not what we are interested in.

What we want instead is a true/false value for whether or not a specific employee is currently employed by a specific employer at a specific industrial establishment. So what we will do is create a temporal value on the Employment object that represents whether, at a given point in time, a person was employed at that location.

To do this, we will use the TemporalFromRange function in OPM, and use the start and end dates of all employments that have the same employer and employee. So the first thing to do is to get a “relevant employment” relationship on the employment object, and define it to include all of the employments that have the same employer and employee. We can create the relationship in the data screen, and create a rule to populate it like this:

Employment (other_employment) is a member of relevant employment if

in the case of other_employment

instanceequals(other_employment employer, employment employer)

and

instanceequals(other_employment employee, employment employee)

and

instanceequals(other_employment industrial establishment,

employment industrial establishment)

InstanceEquals is a function that allows OPM to check whether two relationships refer to the same specific object.

Now that we have a list of relevant employments, we can create a temporal value from them. But you cannot create a temporal value from ranges if there are ranges that do not have one of the relevant values. So we need to create a version of the end date variable that is set to the last possible date (forever in the future) if it is not known.

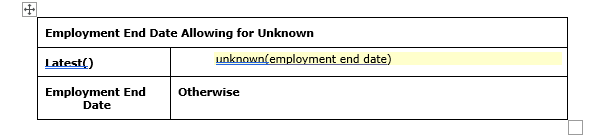

We can do that by creating a table rule in Microsoft Word that looks like this:

So “employment end date allowing for uncertain” will now have a value of latest() (which is what OPM calls “forever into the future”) if the end date is not known. We can now use “employment end date allowing for unknown” in a rule to generate a temporal value.

Employment Employee Employed By This Employer =

TemporalFromRange(

relevant employment,

employment start date,

employment end date allowing for unknown,

True)

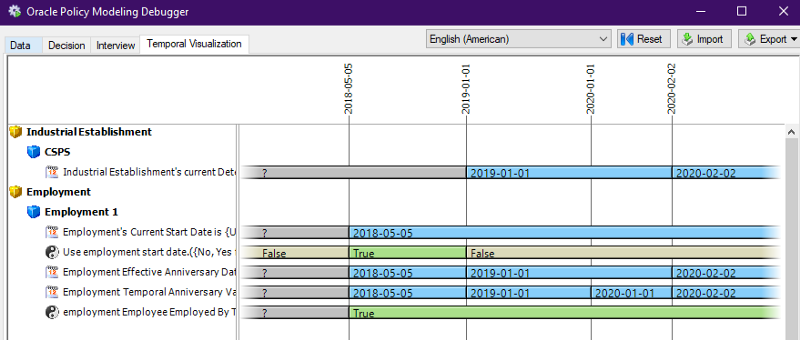

So we have said there is a variable the value of which is True whenever the person was employed by this employer. We can now take a look at this variable in the temporal visualizer.

And we can see that it is true from the start date on until the end of time, as far as we know.

So now we need to ask the question was this person continuously employed by this employer for a period of 12 months? Now, OPM’s temporal values are not temporal functions in the sense that it is an attribute that you can give a date, and it will return a value. Instead, they are a list of values with the dates to which those values apply.

The difference means that when you are trying to generate a new temporal value, you need to figure out what the dates are to which you want the values to apply. Here, we want the value to be “yes or no, the person has worked here for twelve months.” But we are using the value to determine whether or not a year of employment exists. We only are concerned about the existence of years of employment as of their potential start dates.

So, what we will do is generate a temporal value that has a “yes/no” value for whether the person had been employed with the company for 12 months as of the date that a year of employment might start or end.

OPM provides a function called IntervalAlways that allows you to get an answer to the question of whether a temporal value was always true between two dates. We will use that to generate our new temporal value using this rule:

Employment Employee Employed By This Employer for Last Twelve Months =

intervalalways(

the date 1 year before Employment Temporal Anniversary Value,

Employment Temporal Anniversary Value,

employment employee employed by this employer)

We can now check out our new temporal variable in the debugger along side our possible start dates for years of employment.

So we can see that as of the first possible year of employment May 5, 2018, the person is employed, but not employed for the last 12 months. The same is true on January 1, 2019, because at that time they had been employed only 8 months. Then, as of the possible year of employment start on January 1 2020, they have been employed for at least twelve months.

Absence of Start Dates

Our third criteria for whether or not something is a year of employment is whether over the period there were other start dates. We are using this to represent the idea that years of employment must not overlap with one another.

Another way of asking this question is whether the start date has been the same for the previous year. OPM provides a function called IntervalCountDistinct that will check to see how many different values a temporal value has in a period of time. We will check to see if in the previous year it had only one possible start date with a rule that reads like this:

Employment YoE Date Stayed Same For a Year =

if(

IntervalCountDistinct(

the date 1 year before Employment Temporal Anniversary Value,

the date 1 day before Employment Temporal Anniversary Value,

Employment Temporal Anniversary Value) = 1,

True,

False)

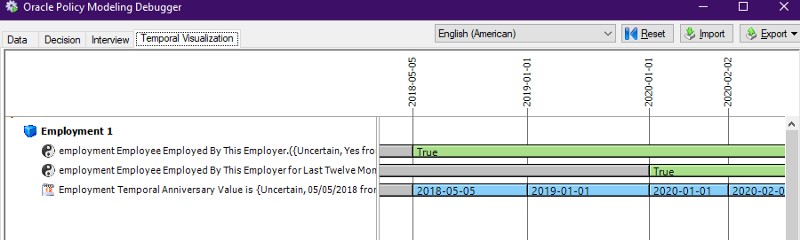

We can now visualize that variable alongside the others:

You can see that the variable was true as of the possible year of employment that started on 2020–01–01, because there had been no change for a year. As of the period starting in February 2020 because of a designated year, it is once again false.

Testing

I want to be clear that I’m not documenting all of the incorrect versions of these rules that I attempted. I’m also not documenting all of the tests that I’m doing with multiple different employment periods, and multiple different designated years, to make sure that the system still works when the data is more complicated.

What I’m describing here is not a realistic account of the moment-by-moment experience of encoding in OPM. Consider this like an instagram account of OPM coding: you only get to see the parts that worked right.

Pausing Here

So we have taught the computer how to recognize the three factors that we need in order to determine whether or not a period of time qualifies as a year of employment. We eventually want to record information about each valid Year of Employment, which means we need there to be Year of Employment instances in the database. So we are going to need to figure out how to use OPM to infer the existence of instances, and assign attributes to those instances.

But this post has covered a lot. And to be perfectly honest, I can’t quite remember how to get OPM to infer the existence of objects in the database.

So now seems like a good time to stop.

Next time, I hope to be able to encode rules that will infer the existence of valid years of employment, and maybe generate an interview that will ask for the relevant information about those periods of time. After that we’ll need another post or two to cover the process of calculating vacation pay, and generating an interview with an explanation.

And if we’re still feeling enthusiastic, we can come back and figure out how to calculate due dates for payment. But this is starting to feel complicated enough.