Playing Along with Rules As Code: Part 4

So today we’re going to get started encoding section 183’s definition of “year of employment.”

This is the fourth in a series of blog posts about following along with the Government of Canada’s Rules as Code discovery project. For details on the project itself, check out Scott McNaughton’s medium page.

Here’s the definition from the source Act:

183 In this Division,

…

year of employment means continuous employment of an employee by one employer

(a) for a period of twelve consecutive months beginning with the date the employment began or any subsequent anniversary date thereafter, or

(b) for a calendar year or other year determined by the employer, in accordance with the regulations, in relation to an industrial establishment. (année de service)

So a year of employment is a period of time that lasts 12 months, during which the person was employed by one employer, and it starts and ends at a specific time that depends on a couple of factors: when the people started, and whether the industrial establishment has determined the calendar year or some other year as the official measurement.

We have years of employment in our ontology, but they are not going to be provided by the user, they are going to be inferred using the rules. So we need to generate the data required to build them, which is start and end dates.

There are two possibilities for the start date. So we need to generate each, and then combine them into a single thing that we can use for generating all of the years of employment.

Anniversaries are simple enough to calculate, so first we need to worry about occasions on which the anniversary date changed (the employee started, or the employer designated a date).

It Gets Complicated (You Knew It Would)

Now, the value is going to be either the employee’s start date at their current employment, or the start date assigned to the industrial establishment.

Except it’s not that easy.

Are we talking about continuous employment in terms of relationships between an employee and an employer, however those relationships might change, as long as they do not terminate? If my job title changes, is that still continuous employment? Probably. If my place of work changes? Seems likely. If I go from one industrial establishment to another without changing employer?

Ooh. Now we have a problem. If a person is continuously employed by the same employer, but in the middle of that employment they are moved from one industrial establishment to another, the way that their vacation is calculated may change if there is a year designated for that industrial establishment.

So the anniversary date that you start from is something that is specific to an employment in a specific industrial establishment. Which means that we are going to be talking about the start date for that industrial establishment, and the set date for that industrial establishment, as the two options.

Note that start of employment for the purpose of figuring out when your year of employment starts is different from start of employment for the purpose of figuring out how much vacation pay you are entitled to. We’re going to have to be careful not to mix them up.

It’s hard to know if we’re following exactly the intended meaning of the section, here. There are other possible approaches. Maybe the definition of industrial establishment is such that it should be type of Employer? It’s the kind of thing we could have been more clear about if we had been using Rules as Code while drafting.

Now let’s talk about the designated date. We could have modeled our ontology around an assumption that a) an industrial establishment only ever has one date defined, and b) we are never going to need to know what the date used to be. And then we could make “designated year start date” an attribute of the industrial establishment.

But there is nothing I can see in the regulation that prohibits an employer from changing the designated year with regard to an industrial establishment. It may also be implicitly possible to undefine one. The law doesn’t say. (Again, it might have said, if we were using Rules as Code at the time). We know for sure the law expects an industrial establishment not have one, and then to have one later, so change is anticipated. And I think people are going to want to know how to calculate vacation pay with regard to the period of time during which the change was made.

So instead of a single attribute, our ontology has a one-to-many “contains” relationship between industrial establishments and determined years of employment, and determined years of employment have a date on which they come into effect.

Temporal Values

Ok, so we’re happy using the start date of the employment, but now instead of just one determined year commencement date, we could have any number of them. The one that applies can change over time.

So we need to create a temporal value out of the events that change the value. Here, the value we are interested is the date on which years are counted as starting. The events that change that date are determinations. It’s not clear to me whether a determination can come into effect on a date different than the anniversary date itself. I’ve allowed for that in the model. If it’s not possible, it means that the anniversary date and coming into effect date will always be the same, which isn’t the end of the world, so we’ll leave it like that just in case.

Now we need to create a temporal value that reflects the current (given any particular date) anniversary date specified by the employer. We do that by using the TemporalFromStartDate() function provided by OPA, and we make a rule in Word that reads as follows:

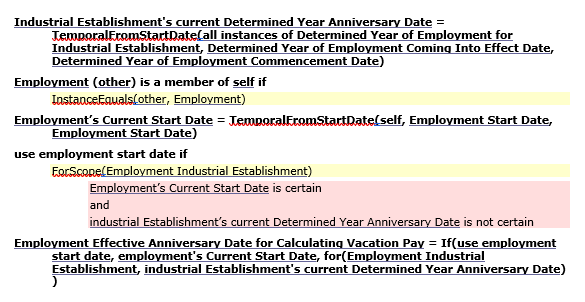

Industrial Establishment’s current Determined Year Anniversary Date = TemporalFromStartDate(all instances of Determined Year of Employment for Industrial Establishment, Determined Year of Employment Coming Into Effect Date, Determined Year of Employment Commencement Date)

(Code in OPM is written in Microsoft Word, but screen shots are not as accessible to people with visual impairment as text, so I’m going to use code blocks whenever they are good enough.)

What this says, in less than perfectly readable language, is with regard to an Industrial Establishment, consider all of the Determined Years of Employment, and for each, set the value of a temporal value to the commencement date as of the coming into effect date. Then put all that information in the attribute called “current determined year anniversary date”.

To test whether or not this is working, you can use OPM’s debugging tool and go in and manually build a few determinations, and then have it display the temporal value for you.

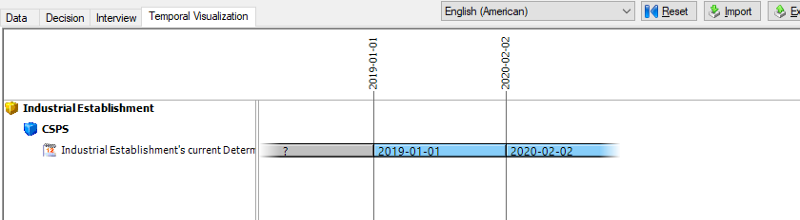

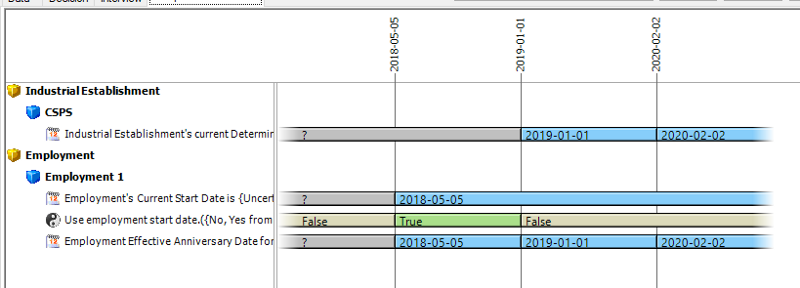

So I created an employer named GoC, an industrial establishment called CSPS, and created two determined years of employment. Then I asked it to visualize the result for me. Here’s what it looks like:

OK, so now we have a single attribute that holds all the changes that happen to the anniversary date. Wonderful. Now what we need is a rule that says that for an employment, the effective anniversary date is either the employment start date, or the current designated date if there is one.

So what we want here is a temporal value that is the combination of two temporal values: the temporal value of the employee’s start date, and the temporal value of the changing designated start date.

We want to say that there is an employment that sets the value to the start date as of the start date. But the methods for creating temporal values in OPM are expecting a list of entities, not a single value. So we need to turn an employment into a list of employments.

Yeah, I know. Just bear with me.

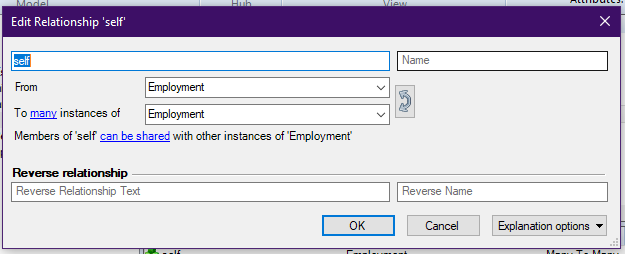

OK, so we are going to do some weird stuff with relationships, here, and add a “self” relationship to the Employment object. Now in reality, we only ever want this relationship to point back to the object it’s coming out of. But, you can’t infer relationship with regard to one-to-one relationships, so we need to pretend that self is a many-to-many relationship.

Now, we need to write a rule that infers the relationship between an entity and itself. So we do this:

Employment (other) is a member of self if

InstanceEquals(other, Employment)

OK, now, if we create an employment, it is its own self. Jeesh.

This doesn’t mean anything, we’re just trying to get the software to do what we want.

Now we can write a rule that refers to a set of objects in order to get a temporal value with only one data point:

Employment’s Current Start Date = TemporalFromStartDate(self, Employment Start Date, Employment Start Date)

And we’re done. If I ask for the value of “employment’s current start date” as of now, I get the start date. If I ask for the value as of prior to the start date, I get “unknown.”

Combining Non-Boolean Temporal Values

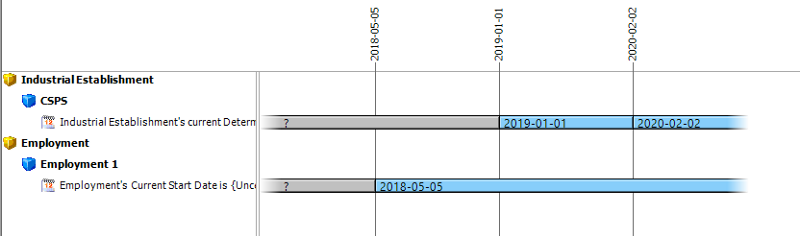

So now we have two temporal values. One represents the start dates for designated years as they have changed over time, and the other represent’s the employee’s start date for the employment. Here’s what they look like if you visualize both together.

The question marks in the grey area refer to periods of time for which the value is unknown. That’s another excellent feature of OPM for Rules as Code purposes, that all variables are potentially unknown, and uncertain, in addition to having specific values.

So now we need to do some logic using these two temporal values to create a third, which is the currently applicable anniversary date. What we need to say is that date is the designated date when the designated date is known, and it is the employment date otherwise.

The easiest way to combine temporal variables using conditions is by using the if() operator in OPM. But it requires a statement for the condition for when to use one variable and when to use the other. So we need to create a temporal boolean value for when the correct date is the employment start date.

We can do that by writing this rule:

use employment start date if

ForScope(Employment Industrial Establishment)

Employment’s Current Start Date is certain

and

industrial Establishment’s current Determined Year Anniversary Date is not certain

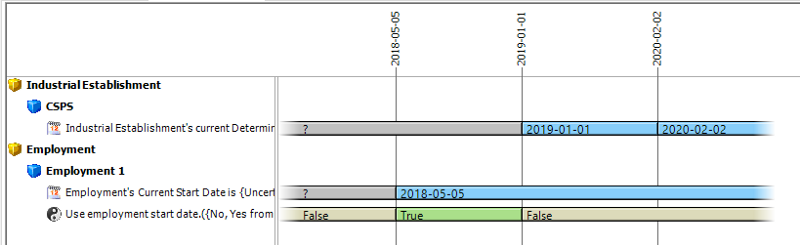

We can now chart that in our temporal graph, and it looks like this:

You can see that it is a temporal boolean value whose value changes between True and False depending on the date.

Now we can use those three variables in another rule to create a fourth. We start with a rule:

Employment Effective Anniversary Date for Calculating Vacation Pay = If(use employment start date, employment's Current Start Date, for(Employment Industrial Establishment, industrial Establishment's current Determined Year Anniversary Date) )

It’s not exactly poetry, but it works. Then we get to visualize our new attribute.

Now we have the temporal data we need to start from for calculating years of work.

Some Thoughts

So what we have above is not terribly complicated as a finished product. Here’s what it looks like inside Microsoft Word.

But this is not your typical Oracle Policy Modelling stuff. Temporal values, inferred self-references, and creating boolean temporal values in order to combine non-boolean temporal values with if statements is… advanced.

I don’t want you to look at this and think “if that’s what it normally looks like, I could never do that.” This is decidedly NOT what it normally looks like. The people at the Government of Canada have just done an excellent job at finding a small piece of legislation with a lot of complexity.

Some of that complexity comes from the fact that the passage of time is important, and inferences change with events. But some of it also comes from the fact that OPM doesn’t allow for defeasible rules, which means that the exception in section 183 (start date unless the employer says otherwise) can’t be encoded in that way. We have to come up with a formula that incorporates the exception, instead.

And we haven’t even finished with section 183’s definition of year of employment, yet. We’re just getting started!

On Oracle Policy Modelling

OPM has a lot of cool features like a nice graphical user interface for data ontology, and editing rules in Word, and automatically generated interviews and data types that include uncertainty by default, and explanations, and more.

But there is a lot about the development experience that leaves something to be desired. Writing rules in a controlled natural language, like OPM allows, has always seemed to be to be a double-edged sword. When it’s done, you can read it. But writing it is very challenging because it is so close to natural langauge. It is so easy to write something that means the exact same thing in natural language and means nothing, or something completely different, to OPM.

“With regard to the employer” will get you a new attribute you didn’t want. “In the case of the employer” will let you refer to attributes in the object referred to in the employer relationship. How a beginner is supposed to remember the difference, I don’t know. There is an auto-complete function for building rules designed to help that has too many things in it, many of which mean the same thing, and some of which are so devoid of context that you have no idea what they mean.

This isn’t to say that OPM is not clearly the best tool currently available for Rules as Code experimentation. I think it is. My LLM research was into what these tools can do, and what they need to be able to do, and OPM is clearly leading the pack.

Critically, it is the easiest to use, and the easiest to learn, of any of the tools currently available. Everything else is more difficult, or just a programming language. It also has features that no other tool I’m aware of has, like the temporal reasoning we have just demonstrated. It has explainability built in (hoping to demo that next time), it automates the generation of interfaces, and it has considerable tooling for testing your encodings against data.

But it is not by any means ideal. Nothing is, yet.

Next Time

Now is a good time to pause, because there are a tonne of interpretation problems with section 183 that we haven’t even gotten to, yet, and that we are going to have to grapple with before we can move any further.

Just you wait. It’s gonna get bad.