Playing along with Rules as Code Part 3

This is the third in a series of posts were I follow along with the Government of Canada’s Rules as Code discovery project. In this post, I’m going to start modelling the legislation in Oracle Intelligent Advisor.

Check out the first post for an explanation of the source material, and the second post for an explanation of why we’re starting again in OIA after having begun in Flora-2.

Ontology Take 2

The ontology we are going to build here is going to be smaller than the one we started with, because we are only aiming at being able to answer questions about vacation pay. Specifically, we are aiming only to be able to answer questions about how much vacation pay a person is entitled to. Because I like things more complicated than they need to be, I’m going to also try to answer question about when that pay is due.

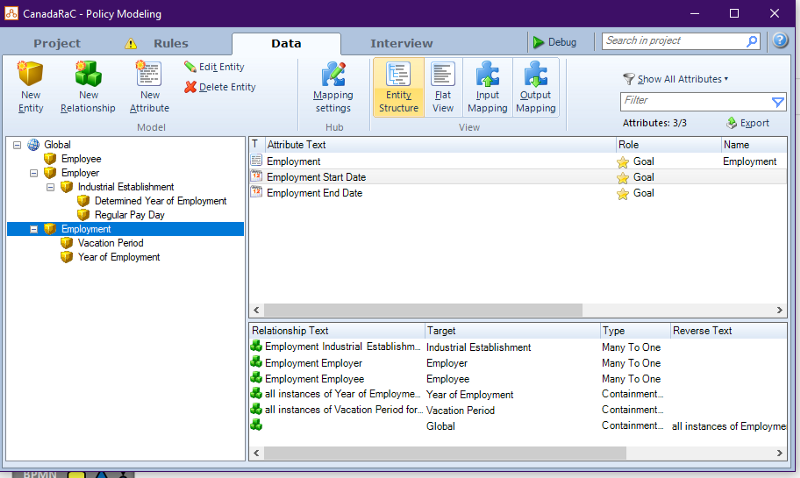

The tool that you use to generate the ontology when using Oracle Intelligent Advisor is the “Data” section of Oracle Policy Modelling, which looks like this:

You can see that the screen is divided into three parts. The left part is a tree-structured list of “entity types”. Each entity type has a list of “attributes” in the top right, which are base data-type information about that entity type, and “relationships” on the bottom right, which are relationships between this data type and other data types.

Unlike in Flora-2, OPM allows you to specify at the ontology phase that relationships are one-to-one, one-to-many, or many-to-many.

The tree structure for entity types expresses a “has” relationship, which is always one-to-many. The entity type closer to the root “has” one or more objects of the entity type below. Entity types that are not contained by anything else are contained by the Global object.

So a text description of what the entity type tree above says might be:

The Global Object has one or more Employees, one or more Employers, and one or more Employments.

An Employer has one or more Industrial Establishments.

An Industrial Establishment has one or more Determined Year of Employment, and one or more Regular Pay Days.

An Employment has one or more Vacation Period, and one or more Year of Employment.

When you click on one entity type in the tree, the interface shows you the attributes and relationships for that entity type. The relationships list will always include the “is part of” relationship to its parent entity type, and the “has a” relationships to sub-types. So “Industrial Establishment” has a relationship to its parent “Employer” by default.

You can see in the image above that “employment” has a relationship to employer, employee, industrial establishment, and all instances of the sub-entities of vacation period and year of employment. An employment also has two attributes, a start date and an end date.

All entity types have, by default, an attribute with the same name as the entity type, that serves as the “name” of that entity until you decide to replace it with something else.

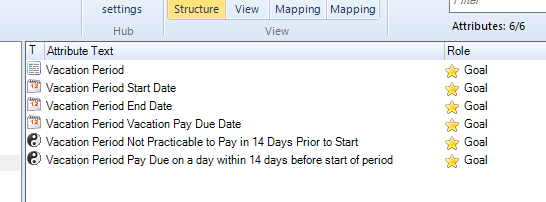

The attributes of a Vacation Period are shown here, and consist of a start date, end date, pay due date, a boolean (yes/no) variable for whether it is practicable to pay vacation pay within 14 days prior to the start date, and a boolean for whether that is when the vacation pay is due.

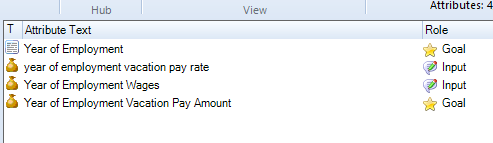

A year of employment is an object with three attributes, a vacation pay rate, wages, and a vacation pay amount owing.

I won’t go through the rest of the ontology line by line, but that should give you an idea how it’s structured. You’ll notice that a lot of the names used in OIA are verbose. “Year of Employment Wages” could just be called “Wages”. There are a couple of reasons for that. First, OIA attempts to automatically determine what entity type your attribute belongs to. Leaving the name of the entity type in the name of the attribute makes sure that it guesses correctly.

But more importantly, OIA re-uses all of the names of attributes and relationships and entity types directly in rules, interview screens, and explanations, so it’s important to use terms that will not be ambiguous. In all likelihood we will want to come back and change a bunch of the names once we can see better how they are being used. But for now we will be verbose.

Getting Started with OIA Rules

The rules that you write for OIA are written in an obscure application you may have heard of called Microsoft Word. Just to give you a little preview, I created a couple of simple rules to implement section 184.01 of the relevant Act, which is reproduced here:

Calculation of vacation pay

184.01 An employee is entitled to vacation pay equal to:

(a) 4% of their wages during the year of employment in respect of which they are entitled to the vacation;

(b) 6% of their wages during the year of employment in respect of which they are entitled to the vacation, if they have completed at least five consecutive years of employment with the same employer; and

(c) 8% of their wages during the year of employment in respect of which they are entitled to the vacation, if they have completed at least 10 consecutive years of employment with the same employer.

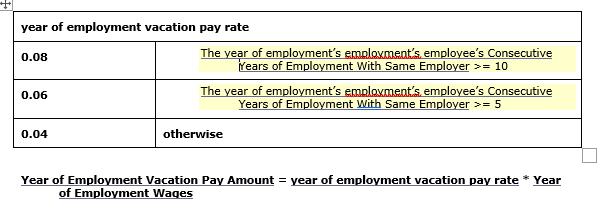

OIA allows you to write rules using a decision table style, using a textual style, and using math-like assignment statements. We’ll get into textual rules more next time, but here’s a decision table and an assignment statement to implement 184.01. This is just a first draft and probably doesn’t work. We’ll fix it later.

The highlighted sections show sections of code that are “conditions”. The underlines show references to variables about which OPM already knows. Notice how you can traverse the entity tree in a really intuitive way by saying “the year of employment’s employment” to refer to that relationship, and then saying “the year of employment’s employment’s employee” to refer to a second relationship out, and then “the year of employment’s employment’s employee’s consecutive years of employment with same employer” to get to the attribute of an object that is two relationships away from year of employment.

This is OIA’s super-power. When you name the entities well, the rules are very easy to intuitively write and read.

Statutory Interpretation Rears It’s Ugly Head

One of the purposes of the Rules as Code exercise is to show us how we can make rules better by thinking about them in computational terms. And it didn’t take long to find another example.

If we rephrase section 184.01, it reads:

A person is entitled to:

4% of their salary,

6% of their salary if they have worked there more than 5 years, and

8% of their slaray if they have worked there more than 10 years.

The combination of sub-clauses and the word “and” is a bit of a nightmare, here. The general rule is that when you are drafting with subclauses you should be able to combine each subclause with the introduction and know what you need to know, without reference to the other subclauses. Also, if there is an “and” between the last two, you treat them as though there is an “and” between all of them. So we could translate this way:

A person is entitled to 4% of their salary, and

a person is entitled to 6% of their salary if they have worked there more than 5 years, and

a person is entitled to 8% of their salary if they have worked there fore more than 10 years.

When is a person entitled to 4% of their salary? Always? Or only when the other two categories don’t apply? If the three categories are mutually exclusive, why are they joined with an “and”? It can’t be because each is contingent, because the first one isn’t. Are you always entitled to 4%, and sometimes entitled to either 6% or 8% also? Are you always entitled to 4%, and always entitled to an additional 6% after 5 years, and always entitled to an addition 8% after 10?

The solution to this problem is to read the context. In section 184, aperson is entitled to 2 weeks after 1 year, 3 weeks after 5 years, or 4 weeks of vacation after 10. There is a contingency on the first one, and the other conditions are the same, and the relationship is 1 to 1.5 to 2. So I’m taking it from context that the difference in vacation pay was probably supposed to be the same, and we reformulate the section to read:

A person is entitled to 8% vacation pay if they have been there at least 10 years, 6% vacation pay if they have been there at least 5 years, or 4% vacation pay otherwise.

Which is what we put in the decision table above. I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader as to how we might conclude, based on context, that vacation pay was not supposed to be zero for a person with less than a year of employment, in parallel to vacation time.

Coming Attractions

There are a couple of relatively sophisticated things we’re going to need to do to encode these rules. We are definitely going to be using temporal attributes, and we are likely also going to be writing rules that create entities and assign values to their attributes.

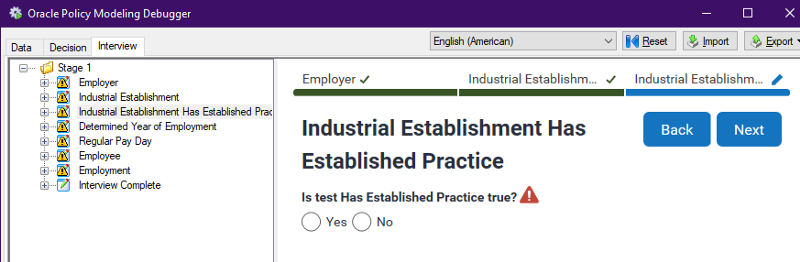

By the way, what we have done already, just setting out the ontology, is enough for OPM to automatically generate an interview that will ask for all of the entities, and for all of the attributes of all of the entities. It’s not able to do anything with the data except parrot it back to you yet, and our attribute names are making the questions a little hard to read, but the debugging interview shown below can be generated with zero additional work.