Playing Along with Rules as Code

The Government of Canada, much to my delight, is currently working on their first-ever Rules as Code discovery project. I’ve decided to play along in the hopes that it will both me and their discovery project team the opportunity to compare notes.

I’m going to chronicle the journey here for people who are interested in seeing it play out in real time.

This series of posts is going to include a lot of code, written in the Flora-2 (aka ErgoLite) programming language. These posts are not intended as a tutorial for Flora-2, but I am hoping to make them useful for non-programmers to read to be able to understand the legal engineering process involved in encoding legislation and using Rules as Code. If you’re not a coder, and you’re not interested in becoming a coder, you should safely be able to skip the code parts. But here’s a quick primer for how to read the code:

This::That. // A This is a type of That.

This[|attribute=>\datatype|]. // A This has one or more attributes

// of type datatype.

This[|relationship=>That|]. // A This has a relationship to one

// or more objects of type That.

I would prefer to be able to play along in Blawx, but the fact of the matter is that Blawx does not currently have the ability to deal properly with dates, which is a critical part of the project that the Rules as Code team has selected. So I’m going to work in Flora-2 directly for now.

The Source Materials

You can follow medium posts on the main project at Scott McNaughton’s Medium Page. That’s my source for everything below.

The Project Scope

In this post Scott sets out that the scope of the project:

We are looking at whether it is possible and what it will take to convert Sections 12 and 13 of the Canada Labour Standards Regulations into machine understandable code.

The Process

I’m following my own process, here, not strictly the sequence of events that the Rules as Code team are following, but I suspect that the general result will be similar. I’m going to begin by looking at the source materials, and figuring out what are all the sections of law and regulation that need to be encoded.

Then, I’m going to try and generate an ontology of the different concepts that it will be important to model. But because I’m familiar with Flora-2, it’s easier for me to do that directly in the programming language than it is to try and do a concept map. So I’ll build an ontology in Flora-2.

Then I’m going to try encoding the rules in the relevant sections of law and regulation, in as isomorphic a way as I can (trying to maintain a one-to-one relationship between the source text and the model). This always reveals problems in the ontology, so I will probably go back and forth between ontology and rules. I’ll try to share that process with you so you can see how it actually works, and not just the final project.

Phase One: The Relevant Source Material

Obviously, we have to start with the two sections of the regulation that Scott referred to above.

Annual Vacations

12 An employer shall, at least 30 days prior to determining a year of employment under paragraph (b) of the definition year of employment in section 183 of the Act, notify in writing the affected employees of

(a) the dates of commencement and expiry of the year of employment; and

(b) the method of calculating the length of vacation and the vacation pay for a period of employment of less than 12 consecutive months.

13 (1) Where an employer has determined a year of employment under paragraph (b) of the definition year of employment in section 183 of the Act, the employer shall, within ten months after the commencement date or after each subsequent anniversary date, as the case may be, of the determined year of employment, grant a vacation with vacation pay to each employee who has completed less than 12 months of continuous employment at that date.

(2) The vacation granted to an employee pursuant to subsection (1) shall be the number of weeks of the employee’s vacation entitlement under section 184 of the Act divided by 12 and multiplied by the number of completed months of employment from and including

(a) the date employment began, for an employee who became an employee after the commencement date of the year of employment referred to in subsection (1); or

(b) the commencement date of the year of employment previously in effect, for all other employees.

(3) Where an employee is entitled to an annual vacation and there is no agreement between the employer and employee concerning when the vacation may be taken, the employer shall give the employee at least two weeks notice of the commencement of the employee’s annual vacation.

(4) An employer shall pay to an employee who is entitled to it the vacation pay referred to in subparagraph 185(b)(i) of the Act or the amount referred to in subparagraph 185(b)(ii) of the Act, as the case may be,

(a) on a day that is within 14 days before the day on which a vacation period begins; or

(b) on the regular pay day during or immediately following a vacation period if it is not practicable to comply with paragraph (a) or if it is an established practice in the industrial establishment in which the employee is employed to pay vacation pay or a proportion of that vacation pay on the regular pay day during or immediately following a vacation period.

So right away we can see that there are parts of these rules that refer to parts of the act. Sections 183–185 are referred to explicitly, so let’s grab those.

Annual Vacations

Definitions

183 In this Division,

vacation pay means the amount an employee is entitled to under section 184.01; (indemnité de congé annuel)

year of employment means continuous employment of an employee by one employer

(a) for a period of twelve consecutive months beginning with the date the employment began or any subsequent anniversary date thereafter, or

(b) for a calendar year or other year determined by the employer, in accordance with the regulations, in relation to an industrial establishment. (année de service)

Annual vacation with pay

184 Except as otherwise provided by or under this Division, in respect of every year of employment by an employer, every employee is entitled to and shall be granted a vacation with vacation pay of

(a) at least two weeks if they have completed at least one year of employment;

(b) at least three weeks if they have completed at least five consecutive years of employment with the same employer; and

(c) at least four weeks if they have completed at least 10 consecutive years of employment with the same employer.

Calculation of vacation pay

184.01 An employee is entitled to vacation pay equal to:

(a) 4% of their wages during the year of employment in respect of which they are entitled to the vacation;

(b) 6% of their wages during the year of employment in respect of which they are entitled to the vacation, if they have completed at least five consecutive years of employment with the same employer; and

© 8% of their wages during the year of employment in respect of which they are entitled to the vacation, if they have completed at least 10 consecutive years of employment with the same employer.

Entitlement to vacation in one or more periods

184.1 A vacation granted to an employee under this Division is to be taken only in one period or, if the employee makes a request in writing and the employer approves it in writing, in more than one period.

Granting vacation with pay

185 The employer of an employee who under this Division has become entitled to a vacation with vacation pay

(a) shall grant to the employee the vacation to which the employee is entitled, which shall begin not later than ten months immediately following the completion of the year of employment for which the employee became entitled to the vacation; and

(b) shall, at any time that is prescribed by the regulations, pay to the employee

(i) if the vacation is taken in one period, the vacation pay to which the employee is entitled in respect of that vacation, or

(ii) if the vacation is taken in more than one period, for each period, the proportion of the vacation pay that the vacation taken is of the annual vacation to which the employee is entitled.

Some of that formatting is messed up, but whatever.

Next thing we’re going to do is look for things that may have specific definitions in the Act or the Regulation, which are relevant to our task.

For example, “industrial establishment” is not exactly a typical turn of phrase, and it appears once in the regulation and once in the act. “Employer” also probably has a more specific meaning, because these acts probably don’t apply to just everyone. But checking the definitions in the relevant section of the Act, “industrial establishment” is basically a list of things done under federal parliamentary authority, and employer is a person who employs people. So for the purposes of this demonstration, we can say that the question of what qualifies as an industrial establishment is out of scope, and what qualifies as an employer is out of scope.

We should be OK with what we have, then. Let’s move on to building an ontology.

Phase Two: Building an Ontology

The basics of ontology in Flora-2 are that you have objects. Objects can be of one or more types. Types can be sub-types of one another. Types also have attributes. An attribute is a list of values with a name, and a data type. A data type can be a “primitive” data type, like numbers, strings of text, or true/false values. An attribute can also be given a datatype that is an object type, so that one object can have an attribute that refers to one or more other objects of the same or different types. An attribute that refers to an object can be thought of as a “relationship”. An attribute that refers to a primitive data type can be thought of as a “property.”

So the question here is what types of objects are these sections of the law referring to, and how do they relate to each other?

Here’s a list, starting from the top:

Section 12

- Obligation

- Deadline

- Employer

- Determination of Year of Employment

- Notification, which may be in writing, has a sender, a list of recipients, and a content, and a date on which it occurred.

- Employee

- Affected Employee

- Year of Employment, which has a date of commencement, and a date of expiry.

- Method of Calculating Length of Vacation and Vacation Pay

- Period of Employment

Some notes, here.

Where did “Obligation” come from? Well, the section includes the words “shall”. Which suggests that there is a thing that someone must do. It might have properties like “who must do the thing”, “what thing must be done”, “the deadline by which things must be done”, and “the consequences for failure to do the thing by the deadline”, if any. Similarly, a deadline is an object that might be a specific date, or it might be a combination of a date and a duration.

Whether you want to or need to go into that level of detail in your ontology is going to depend on the sorts of questions you want the code to be able to answer. For instance, if you want to be able to ask questions like ‘what are the notification dates for the existing determined years of employment’, then “notification date” as a property of a determined year of employment is probably enough. If you want to be able to answer questions like “what is this person obliged to do, and by when”, then having a category of objects for obligations makes a lot of sense.

We’ll make our best guess at what might be useful, here, and change our minds later.

The phrase “affected employee” implies that there are possibly “unaffected employees”. So we are going to need a category for “employee” and a category for “affected employee”, and some rules for figuring out who is in what category. It’s not clear now what they can be affected by, or if there is more than one thing that can affect them, so it makes sense to make it a separate category, instead of a property of the Employee category.

We have added a couple of properties to year of employment: the date of commencement, and the date of expiry. Note, though, that we are making an interpretive choice by doing that. The actual section reads:

the dates of commencement and expiry of the year of employment

There are at least two possible interpretations of that phrase.

We have taken the first option, that this refers to two dates, one the date of commencement, the other the date of expiry, and that a year of employment has one of each. But semantically, the sentence could also mean that a year of employment is an object with a list of dates, and each date may either be a date of commencement and expiry, but neither is required, and there may be more than one of each.

The second meaning is not very likely to be true, in the context. But it is the context, and not the words, that tells you how to model the ontology. One of the principles of the Rules as Code project is that if we drafted in code from the very beginning, we could be more explicit about these sorts of things, and avoid errors or disagreements when people interpret the context differently. But this is not a drafting process, it is an interpretation process, so we are stuck making the best guesses we can.

I’m only going to point out interpretation choices that are particularly difficult, but be aware that virtually every choice is more interpretation than it is transcription.

Here’s what the code would look like for what we have so far. I’m going to use the category “Thing” as the root category of our ontology, just to make it clear when I’m talking about object types, and not specific objects.

Obligation::Thing.

Obligation[|

obliged_entity=>Thing,

obliged_action=>Action,

deadline=>Deadline,

satisfied=>\boolean

|].

Deadline::Thing.

\date::Deadline.

Relative_Deadline::Deadline[|

date=>\date,

duration=>\duration

|].

Employer::Thing.

Determination_of_Year_of_Employment::Thing.

Notification::Thing[|

sender=>Thing,

recipient=>Thing,

content=>Thing,

date=>\date

|].

Employee::Thing.

Affected_Employee::Thing.

Year_of_Employment::Thing[|

date_of_commencement=>\date,

date_of_expiry=>\date

|].

Method_of_Calculation::Thing.

Period_of_Employment::Thing.

Section 13

- Subsequent Anniversary Date of a Year of Employment

- Grant of Vacation

- Vacation, which has a date of commencement, and a duration.

- Vacation With Pay

- Consecutive Years of Employment

- Completed Months of Employment

- Employee’s Vacation Entitlement under Section 184 of the Act

- Start Date of Employment

- Year of Employment Previously In Effect

- Employee Entitled to Annual Vacation

- Agreement Between Employee and Employer About When Vacation Happens’

- A Payment of Vacation Pay

- An employee entitled to vacation pay

- Date of Payment of Vacation Pay

- Regular Pay Day During or Immediately Following a Vacation Period

- The day on which a vacation period begins

- A Vacation Period

- A Pay Day

- A Regular Pay Day

- Practicability to Pay

- Industrial Establishment

- Established Practice in an Industrial Establishment

So we know that a Vacation is one thing, and that a Vacation Period is another thing, and that a Vacation with Pay is another thing. Does that mean that a Vacation is an object that has a true/false property of “with pay”? Does it mean that a Vacation has both a commencement date, and a “period”? Is the start of the period the commencement date? Can it have more than one period, and if so, is the start of the first period the commencement date? Or are vacation periods the same things as vacations, and each has a start date and an end date, but there can be more than one?

We don’t really have a lot to go on for answering these sorts of questions, yet. We can go hunting through the legislation for clues, but there’s a risk of setting up a complicated structure that doesn’t actually get you what you need when it comes time to write the rules. So we’ll make some guesses at some of these things, and come back and fix them later when we know why exactly the guesses are wrong.

For another example, we will say that the duration of a vacation entitlement can be modeled as a duration, which is a primitive data type provided by Flora-2. But we may find later that it needs to be modeled as a number of work days, or a number of weeks, where the word “day” or “week” means something different than it does inside a duration.

For another example, one guess that we are making is that “entitled to annual vacation” is a true/false property that does not apply to an employee, but rather applies to an employment. A person might be employed in two different places, be entitled to vacation in one place and not in the other. So we can make those sorts of guesses as a starting point and go forward from there.

A particularly difficult choice, at this point, is the idea of a “year of employment previously in effect.” That gives rise to the idea of a “year of employment in effect”, and a period of time during which it is in effect. Which determined year of employment is “previous” will depend on the point in time, which means that you need a list of years of employment in effect, and the times at which they were in effect. We could model this with start dates and end dates for effect, but that would leave the possibility that the only years of employment listed are expired, and there is no current valid option. It seems more like this is something that stays true until it is replaced, so we will model it with a start date only, and say that whichever one has the most recent start date will be the one “in effect.” But what object does that get attached to? It seems like “industrial establishment” is where that belongs, but we may have to change that later.

Here’s what we might add to the ontology, at this point. Note that one of the great things about the F-Logic semantics implemented in Flora-2 is that you can come back later and add things. So we can add subsequent_anniversary_date as a property of Year_of_Employment without having to go back to where we wrote it the first time.

Year_of_Employment[|

subsequent_anniversary_date=>\date,

date_of_taking_effect=>\date,

|].

Grant_of_Vacation::Thing[|

employer_and_employee_agreed_to_timing=>\boolean

|].

Vacation::Thing[|

date_of_commencement=>\date,

duration=>\duration,

with_pay=>\boolean

|].

Employment::Thing[|

employer=>Employer,

employee=>Employee,

consecutive_years=>\integer,

completed_months=>\integer,

start_date=>\date

employee_entitled_to_annual_vacation=>\boolean,

employee_entitled_to_vacation_pay=>\boolean,

s184_vacation_entitlement=>\duration

|].

Industrial_Establishment::Thing[|

established_practice=>\boolean,

practicable_to_pay=>\boolean,

regular_pay_days=>\date,

years_of_employment=>Year_of_Employment

|].

Payment_of_Vacation_Pay::Thing[|

payor=>Employer,

payee=>Employee,

amount=>\currency,

date=>\date

|].

For now we’re going to assume that a period of vacation and a vacation are the same thing. We’ll see.

Sections 183–185

The definition of vacation pay doesn’t tell us much, here, except that it is an amount, which I think we already knew, and to look at section 184.01, which we will do later.

The definition of a year of employment suggests that a year of employment has an employee, an employer, and a date of the year on which it starts, which is calculated in two different ways.

So we can see here that there is a difference between a generic “year of employment” which is a period of one year during which an employee has been continuously employed by an employer, and which starts on the date that they start that employment, and a calculated “year of employment” which is a period of time during which an employee has been continuously employed by an employer, and began on the designated year of employment start date that was in effect at the time of… what… the start of the year of employment? I’m not even going to try and figure that out right now.

So we need to change the “year of employment” that we have been talking about thus far to “designated year of employment”. And we need to create a new concept for “year of employment” that will use either the designated year of employment or the employment start date to determine when and whether it exists.

A year of employment is an employer, an employee, and a commencement date. A designated year of employment is a day of the year, and the date on which it came into effect.

So we will delete this:

Year_of_Employment::Thing[|

date_of_commencement=>\date,

date_of_expiry=>\date

|].

Year_of_Employment[|

subsequent_anniversary_date=>\date,

date_of_taking_effect=>\date,

|].

And replace it with this:

Designated_Year_of_Employment::Thing[|

commencement_date=>\date, // The Year of this date is meaningless

date_coming_into_effect=>\date

|].

Year_of_Employment::Thing[|

employee=>Employee,

employer=>Employer,

start_date=>\date

|].

We will also replace

Industrial_Establishment::Thing[|

established_practice=>\boolean,

practicable_to_pay=>\boolean,

regular_pay_days=>\date,

years_of_employment=>Year_of_Employment

|].

with this:

Industrial_Establishment::Thing[|

established_practice=>\boolean,

practicable_to_pay=>\boolean,

regular_pay_days=>\date,

designated_years_of_employment=>Designated_Year_of_Employment

|].

Section 184 has an interesting wording:

Except as otherwise provided by or under this Division, in respect of every year of employment by an employer, every employee is entitled to and shall be granted a vacation with vacation pay of

We’re not trying to write the rule, right now, we’re just trying to understand the structure of the data. Writing the rule for this section will be interesting, too, for different reasons.

But the question that comes up here in the ontology part is whether an entitlement to a vacation with vacation pay and an obligation to grant a vacation with vacation pay are two objects, or one object.

Is it true that a person is entitled to everything that a person is obliged to do for them? Can we model an “entitlement” as an obligation for an action where the action has a recipient and the action is generally considered in the recipient’s favour? Is that helpful?

It would seem, off the bat, to say that if every employee is entitled to something and shall be granted that thing, that the two go together. But the section also says “except as otherwise provided,” which raises the possibility that a different provision could change the entitlement, but not change the grant, or change the grant, but not change the entitlement.

I’m going to say that for now, an entitlement and an obligation to pay are the same thing. And because we already have a data model for obligations, section 184 doesn’t actually need any additional ontology. We already know how to talk about all the things it refers to.

Similarly, section 184.01 only adds one idea to the ontology:

Year_of_Employment[|

wages_during=>\currency

|].

Section 184.1 adds the concept of a request and approval, and clarifies that a grant of vacation can have more than one period. We can also see that a grant of vacation is now with regard to a given year of employment.

Year_of_Employment[|

vacation_grants=>Grant_of_Vacation

|].

Grant_of_Vacation[|

periods_of_vacation=>Vacation,

requests=>Request_for_Multiple_Period_Vacation

|].

Request_for_Multiple_Period_Vacation[|

employer=>Employer,

employee=>Employee,

approved_by_Employer=>\boolean

in_writing=>\boolean

|].

Section 185 puts the lie to the idea that entitlement and obligation are the same thing. It says that with regard to a person who is entitled to vacation, the employer shall grant it. If the definition of an obligation to grant vacation and the definition of an entitlement were the same thing, then this section would be meaningless.

So we need to correct our ontology to say that with regard to a year of employment there is an entitlement to vacation and an entitlement to vacation pay, and obligations to grant vacation or pay vacation pay are different things. We currently have s184_vacation_entitlement as a property of an Employment, so we will delete that. We will instead add a vacation entitlement and a vacation pay entitlement to the Year of Employment object.

Year_of_Employment[|

vacation_entitlement=>\duration,

vacation_pay_entitlement=>\currency

|].

Wrapping Up Phase Two

Here is a code block summarizing what we’ve got after all the above is done.

Obligation::Thing.

Obligation[|

obliged_entity=>Thing,

obliged_action=>Action,

deadline=>Deadline,

satisfied=>\boolean

|].

Deadline::Thing.

\date::Deadline.

Relative_Deadline::Deadline[|

date=>\date,

duration=>\duration

|].

Employer::Thing.

Determination_of_Year_of_Employment::Thing.

Notification::Thing[|

sender=>Thing,

recipient=>Thing,

content=>Thing,

date=>\date

|].

Employee::Thing.

Affected_Employee::Thing.

Designated_Year_of_Employment::Thing[|

commencement_date=>\date, // The Year of this date is meaningless

date_coming_into_effect=>\date

|].

Year_of_Employment::Thing[|

employee=>Employee,

employer=>Employer,

start_date=>\date,

wages_during=>\currency,

vacation_grants=>Grant_of_Vacation,

vacation_entitlement=>\duration,

vacation_pay_entitlement=>\currency

|].

Grant_of_Vacation::Thing[|

employer_and_employee_agreed_to_timing=>\boolean,

periods_of_vacation=>Vacation,

requests=>Request_for_Multiple_Period_Vacation

|].

Request_for_Multiple_Period_Vacation[|

employer=>Employer,

employee=>Employee,

approved_by_Employer=>\boolean

in_writing=>\boolean

|].

Method_of_Calculation::Thing.

Period_of_Employment::Thing.

Vacation::Thing[|

date_of_commencement=>\date,

duration=>\duration,

with_pay=>\boolean

|].

Employment::Thing[|

employer=>Employer,

employee=>Employee,

consecutive_years=>\integer,

completed_months=>\integer,

start_date=>\date

employee_entitled_to_annual_vacation=>\boolean,

employee_entitled_to_vacation_pay=>\boolean

|].

Industrial_Establishment::Thing[|

established_practice=>\boolean,

practicable_to_pay=>\boolean,

regular_pay_days=>\date,

designated_years_of_employment=>Designated_Year_of_Employment

|].

Payment_of_Vacation_Pay::Thing[|

payor=>Employer,

payee=>Employee,

amount=>\currency,

date=>\date

|].

This is by no means perfect. But it’s a decent start, and the problems with it will become more apparent when we start trying to code rules. It has 19 or so category types, include two sub-categories for deadline. It has 45 type attributes, of which 18 are relationships between different types of objects.

Some of those relationships are to objects of type “Thing”, which means anything at all, which is going to need to be cleaned up. Clearly, a Grant of Vacation is not the sort of “Thing” that can be obliged to do anything, or can be the sender of a notice. We will want to use some more generic types like Person to describe those sorts of relationships.

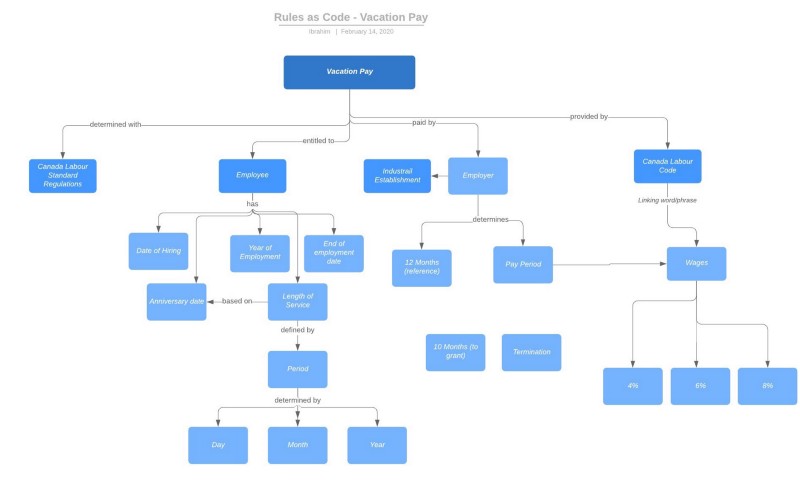

How it Differs

Now that I’m done, I can take a look at what the Rules as Code people at the Government of Canada have done over the last two weeks, and compare. Check out this post from Scott McNaughton for the details, but here is a helpful diagram he includes in that post.

So to start you can see that there is a difference in focus. Consider the inclusion of the three different percentages relevant from 184.01. They include those three percentages and link them to the concept of “wages”, because applying those percentages to wages is how vacation pay is calculated.

For my purposes, I’m trying to figure out an ontology that I can use to write rules. The rule will set out how to calculate the entitlement to vacation pay. What I need to accomplish at the ontology stage is just to teach it that “entitlement to vacation pay” is a thing, and that it holds a piece of information that will be a currency, and that it is associated with a year of employment.

I also have a wages attribute, which is attached to the year of employment type of object, but it isn’t attached to the percentages (which aren’t specified anywhere), because floating point numbers are a thing that the computer already knows how to talk about.

Some other things they include that I don’t include “termination”, and the name of the legislation and regulation themselves, and some specific periods of time. Including the regulation and law names is an interesting idea, because it allows you to “say” things like “rules in the law” and “rules in the regulation”. One reason to do that in the ontology might be to make it so that an act has parts, parts have sections, and a rule is associated with a section, and can use statements to the effect of “this part” to refer to the part of the legislation the current rule was found in.

That’s some pretty advanced stuff, though, and definitely beyond what I want to try to implement.

Including termination is an interesting idea. The concept of termination could be added to my ontology be putting an end date in the Employment object, for example. That might be useful for creating a definition of “affected employee” that requires that the employee still be employed. It will be interesting to see how far I can get without it.

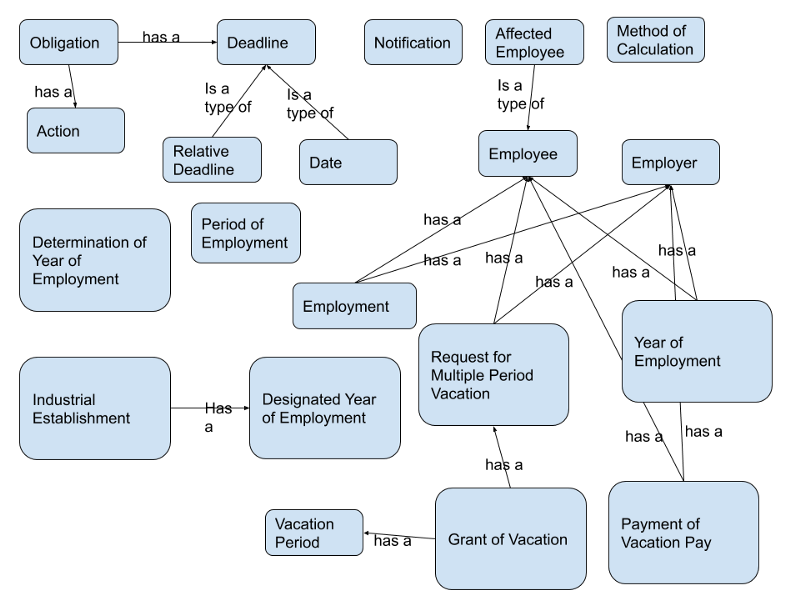

The main reason for the difference between the two charts is that the Rules as Code process is using a human-centered way of connecting ideas. I’m using an ontology that has a specific semantics. So as boxes I’m only creating categories of entities, and the relationships between those types of entities. If you take out the data-type attributes, it looks something like this:

Is one of these better than the other? I don’t know. The Rules as Code discovery process is designed to achieve more than merely encoding a piece of legislation. What I’m aiming at is just a faithful, isomorphic representation of what’s already there. It may be horses for courses.

My instinct is that declarative logic programming is a better tool for encoding legal rules than most. And with regard to declarative logic programming, at least, an iterative process that goes back and forth between ontology and rules seems like the most realistic way to approach these sorts of problems. Knowing in advance the semantics available to you in your coding tool allows you to build your ontology in a way that is going to be more closely related to the end result, and will save time by avoiding the need to reformulate concepts later.

So I certainly think there’s something to be said for a semantically strict ontology over a semantically lax one, in terms of how close it gets you to the end result. But I’m a lawyer getting a masters degree in Computational Law. I’m not a statistically valid sample.

Next Time: Rules

Next time we’ll get started trying to convert some of the rules in the source material to rules in Flora-2. I don’t know when the government’s project will get to that point, but I’ll try to keep pace.