Innovation Achieved

I believe the access to justice problem cannot be significantly improved in the short or medium term without automating legal services. One of the difficult aspects of automating legal services has been finding a way to automatically get explainable predictions for subjective, discretionary legal issues.

What does that mean with less jargon? Computers have been pretty good, for at least the last 40 years, at telling you whether or not you are a citizen, or what your taxes should be. The answers are clear cut. They have been less useful for telling you whether or not you were negligent, or whether your use of force was reasonable in all the circumstances. Those legal concepts have been too fuzzy for expert systems.

The American Bar Association’s Center for Innovation awarded me an Innovation Fellowship to try and fix that. I’m happy to announce that the main goals of that project have been met.

Phase 1: Add Analogical Case-Based Reasoning to docassemble

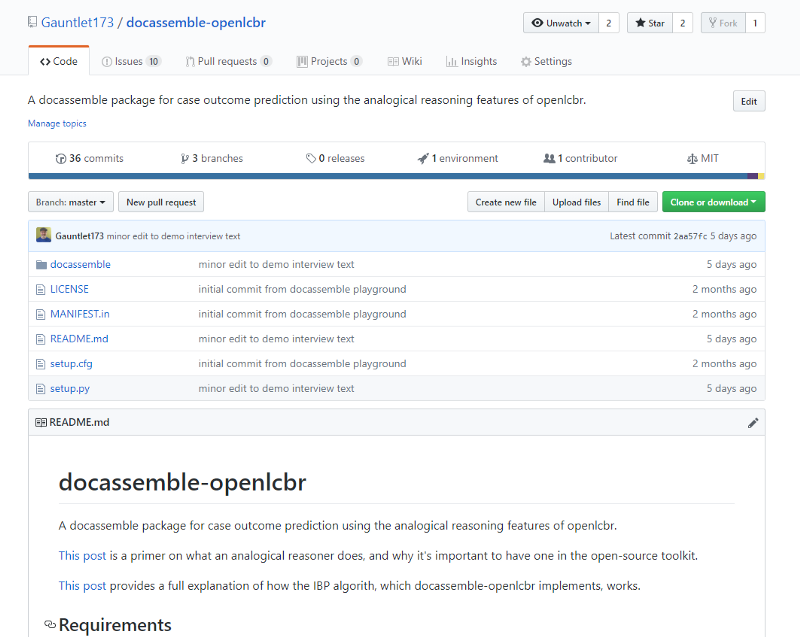

Docassemble is the leading open-source tool for building legal interview and document automation tools. OpenLCBR is an open-source implementation of the IBP algorithm for automating case-based reasoning by analogy. Phase 1 of the project involved writing a piece of software, docassemble-openlcbr, to make it possible to use openlcbr inside a docassemble interview.

☑ Done.

In this post I describe the results of that phase, and in this one I explain how the IBP algorithm works.

Phase 2: Build Tools for Building Analogical Reasoners

Docassemble-openlcbr tool allowed you to run an analogical reasoner, but it didn’t provide you any convenient way to build one. Phase 2 of the fellowship project was to build a tool that would allow non-technical users (read: lawyers) to build an analogical reasoner in a user-friendly interface.

☑ Done.

In this post I describe the results of that phase.

Phase 3: A Demonstration Reasoner and Interview

The last phase of the project was an experiment. The goal was to generate a new analogical reasoner using the tools I had developed in Phase 2, and then use that reasoner along with the tools I had developed in Phase 1 to create a website that automated a legal service that required answering a subjective question in an access-to-justice area of law.

There were a number of things that I wanted to learn:

- If you build an analogical reasoner in docassemble-openlcbr, does it work?

- Do the tools work properly? How can they be improved?

- How hard is it to build an analogical reasoner that works? Is the effort worth what you get out of it?

- What is the process for the legal expert in building an analogical reasoner? What are some of the problems that you experience, and what are some of the things you can do to make the result better?

I’m going to give you the answers here.

The Phase 3 Process

Choosing a Target

The first part of the process was choosing a purpose for the tool. I have been doing a lot of research into automating the law surrounding common law relationships in Alberta in the course of my LLM in Computational Law at the University of Alberta. That legislation was a good choice for automating with analogical reasoning, because there are very few elements of the legislation which are subjective, and the rest could be automated relatively quickly.

So I decided that my analogical reasoner would be designed to answer the question: “are these two people in a relationship of interdependence”. That is one of the factors that is used to determine whether or not a couple are in a common law marriage, which is called an “adult interdependent partnership” in the legislation.

So the reasoner would answer the “relationship of interdependence” question, and the interview would use that reasoner’s prediction to answer the larger “adult interdependent partnership” question.

Doing the Research

Due to the limitations of time, I decided to set a hard cap of 50 on the number of cases that I would review in designing the reasoner. Using CanLII and a commercial research tool, I looked for court decisions in Alberta citing the relevant sections of the act, and referring to the phrase “relationship of interdependence.” In a matter of a couple of hours I had a list of 50 cases which seemed on their face to be relevant.

Building the Issue Tree and Factor List

If you want some background on how the IBP algorithm works, and what you need to put into the reasoner, check out this post from a few weeks ago.

The first thing I did was use my Phase 2 reasoner builder to add all of the cases to the database. This was a relatively painless data-entry task. I included links to the CanLII versions of the cases so that I could go straight from my reasoner builder to the text of the cases.

The second thing that I did was take a first-pass at designing the issue structure, and the list of factors. As it turns out, the legislation provided something of an issue structure for me. The issue of whether the parties are “living together in a relationship of interdependence” is divided into three parts, all of which need to be satisfied. I created a simple issue tree with a root issue and three conjunctive sub-issues. As it happens, I never changed that structure.

The legislation was also helpful with regard to factors. Specifically, it had a long, but not exhaustive list of factors that should be taken into account when deciding the third of the three sub-issues, specifically, whether or not the parties are “an economic and domestic unit”.

I added all of those factors to the database, and indicated in the reasoner builder that they were all relevant to the third sub-issue. The problem, at this point, was that I had no factors specifically relevant to the first and second sub-issues. My plan was to figure out from the cases which factors had led judges to make decisions on those two sub-issues, and update the issue tree later.

Annotating the Cases

I then went through the cases, one-by-one, making a number of decisions about each of them.

First I needed to decide if they were relevant, and should be included in the database.

Many cases I ended up removing from the database for reasons I hadn’t anticipated. For example, some cases decided that a relationship of interdependence existed, but did so without any mention of any facts that supported that conclusion. In other cases, factors were mentioned, but the issue of whether there was a relationship of interdependence was not contested as between the parties, and so the judge’s statements were obiter.

If the case was relevant, I tried to answer the following questions:

- Which of the factors we know about were found to exist in this case?

- What factors did the judge consider that are not in my list of factors, and should they be added?

- What does this case tell us about how the issue tree should be structured?

Courts are very happy to follow legislated lists of factors to consider, and so the cases quite reliably and quite explicitly told me what factors were and were not found to be relevant among those listed in the legislation. Some of the factors listed in the legislation were too general to be meaningful, and could not be included in the factor list as-is. One example is a factor that asks the court to consider “the parties’ conduct with regard to” something. The legislation clearly contemplates that the conduct may militate for or against finding a relationship of interdependence, but the IBP algorithm requires that factors lean only in one direction. So I looked in particular for more specific examples of facts that would fall under those broader categories of factors.

I also looked carefully for factors relevant to the first two sub-issues, with not much success. These matters rarely seemed to be contentious.

In the end, I had a list of 17 factors, only around 8 of which had been taken directly from the legislation.

If I decided a factor needed to be added, that necessitated going back through the cases that had already been annotated to see if that factor had been addressed in those cases, which was slow, and boring.

This annotation process also clarified for me the circumstances in which I would say that a certain factor was met, and the circumstances in which I would not. I documented those decisions as I went along, and that documentation became very useful later, when writing the interview questions.

The Issues Tree Revisited

Once I had gone through all of the 50 cases, removing a few duplicates that had come up under multiple styles of cause, removing irrelevant cases and unhelpful cases, I was left with only 28 annotated cases. I then took another look at the issue tree.

Each of the first two sub-issues had a small list of less than 5 relevant factors each. And the first two sub-issues had been decisive of the issue in none of the cases in the database. As such, I indicated in the reasoner builder that these two sub-issues could be presumed to be proven if there were no relevant factors in the test case.

At this point, I ran a test, and discovered that the reasoner predicted 72% of the cases in the database correctly. Which sounded very good, until I realized that the reasoner was predicting the existence of a relationship of interdependence in every case. It just so happened that 72% of the cases had found the relationship of interdependence existed.

This was effectively the “good ol’ rock, nothing beats rock” strategy that Bart Simpson employs. Not good enough.

I looked more closely at the way the reasoner was attempting to predict each of the 28 cases it knew about using the other 27, and discovered that the problem was the relatively small number of factors in the list that militated against finding a relationship of interdependence.

This was a problem because of a difference in the way that judges reason about cases, and the way that the algorithm reasons about cases. Specifically, a judge may find that people are not in a relationship of interdependence because not enough of the indicia are proven to exist. But the reasoner cannot make decisions on what it does not know. If you tell it that a factor does not exist, it does not take into account the possibility that it might have, and discount the few factors that do.

So the main tuning task was to go through the list of factors and determine which ones should be converted from positive statements in favour of finding a relationship of interdependence, and turned into negative statements in favour of not finding one.

I did this by taking a look at the frequency of each of the factors across the two categories of cases. I noticed that certain things almost never happened in cases where the relationship was not found, and almost always happened in cases where it was. So I tried taking four of those factors, and converting them from a positive to a negative factor.

For example, instead of a factor favouring the finding of a relationship of interdependence that asks “do the parties have shared property,” the factor because one that disfavours that finding and asks “do the parties not have shared property”.

The result of this change put the over-all accuracy of the tool down to 60%. Which sounded bad, until I looked at why. As it turned out, it was actually predicting correctly in all but two cases, if it predicted at all. And what’s more, it was now predicting correctly most of the time in both cases where the relationship was found to exist, and in cases where it wasn’t.

The reason the percentage had gone down was that it was abstaining in a large number of cases, because a larger number of cases had factors leaning in both directions.

Conflicting factors are dealt with in the algorithm in part through knock-out factors. So I took a look at all of the cases that were being abstained from, and found that most of them were abstaining on the basis of one or two cases in the database that ought not have been carrying that amount of weight. So I took a look at the factors in those cases compared with the cases they were being compared against, and looked for factors that ought to be more important in the second category.

That led me to two factors. The first was essentially the parties having jointly claimed the existence of an adult interdependent partnership in prior sworn proceedings. The second was whether the relationship between the parties was exclusive. Cases in which the relationship was not found to be exclusive were overwhelmingly decided against finding a relationship of interdependence. I added those two knock-out factors to the reasoner, and ran it again.

Running the tests again, I got the following results:

- 28 cases total

- 4 abstentions, 24 predictions

- Of 24 predictions, 22 were accurate

- 1 False Positive

- 1 False Negative

That works out to 86% coverage, with 92% accuracy on covered cases. And the balance between errors in one direction and errors in the other was comforting.

And at that point, I stopped working on it.

How Much Work Did It Take?

All told, the total amount of time spent doing the research, annotating the cases, and tuning the reasoner, was in the range of 20–30 hours. Less than a week. Maybe ten times as long as it would have taken to answer the question for a single client.

I then build an interview that could use that reasoner, and could deal with the other aspects of determining whether or not a person was in an adult interdependent partnership. As it happens, the algorithm for doing the math on periods of separation and attempts at reconciliation was quite complicated, and it took about 16 hours to get the interview working.

Each of the factors in the database needed to either be calculated or asked about directly in the interview. Some of the factors could be calculated based on the answers to questions the interview needed to ask anyway. For the remainder, I wrote questions that would allow a non-expert to provide a reliable answer as to whether the factor existed, if they were familiar with the relationship.

The decisions that I had made and documented about the circumstances in which I would code a factor as existing or not in a given case were very helpful in explaining that same information to the user in the interview, to help ensure that the user would be using the same definitions that the reasoner was.

Lessons Learned

Does it Work? Yes.

It’s hard to argue with 86% coverage, 92% accuracy, and a balance between false negatives and false positives. For the amount of time that was spent building the reasoner, I’m impressed with that result.

Clearly, a more robust prediction engine could be built, that takes into account a wider variety of factors and a larger database of cases. And there are more robust ways of measuring the accuracy of a prediction tool, ideally by testing it against cases it has never seen, and by comparing its predictions to the predictions of experts.

But the goal of the project was not to prove that my reasoner in particular was strong. The goal of the project was to see if an analogical reasoner could be. I think there is strong reason to keep studying it.

How Can the Tools Be Improved?

Without getting into a lot of details, there are aspects of the workflow for building a reasoner that I did not anticipate, such as having to loop back to the first case again whenever you add a new factor. A tool that allowed you to track which of the factors you had examined already for each given case would be helpful.

The reasoner builder is also a bit of a one-way street, because docassemble is not a general purpose application tool, but an interview tool. You don’t typically change your mind and go back and change your answers in an interview. Once you have made changes to the cases, you can’t go back and make changes to the factors without undoing what you have done to the cases. That required finishing the interview, downloading the reasoner, then re-starting the reasoner a number of times.

So there are opportunities to make the tools match the lawyer’s workflow better. There are also opportunities to integrate the testing results more closely with the reasoner builder, so that you can see what effect your changes are having right away.

Is it Worth the Effort?

As I mentioned on Twitter while I was working on the reasoner, the work of annotating the cases was time-consuming and dull. But I was using my judgment with regard to the law, and my knowledge and understanding of the algorithm. I was also turning what I knew about the law into something permanent, a commodity that could be used by any number of people. For those reasons, it felt like time well-spent, in stark contrast to any time I ever spent drafting a memo.

That feeling has value, though it is obviously hard to quantify.

All told, the task of building and tuning the reasoner and building the demonstration interview took me in the range of 40 hours. That’s not an inconsiderable amount of time. But that is without any assistance in finding relevant cases, annotating them for factors, determining their relevance for a given legal issue, all of which are things that are increasingly possible to automate using machine learning research tools.

It remains to be seen what the ultimate quality of these reasoners will be as prediction engines, and that will be the most important factor in determining whether the time spent building them is well spent. But one presumes they will only get better, and get easier to build.

It is absolutely clear to me that there is a category of legal problems for which building an analogical reasoner is a cost-effective solution.

Problems

Figuring out how to divide the factors between those where their presence is significant and those where their absence is significant is a difficult problem, and I anticipate that there are principles to be followed there. Figuring out how to convert a factor in legislation which speaks of a range of values and turning that into one or more true-or-false factors is also challenging. Determining whether a number of seemingly overlapping factors are actually all factors relevant to a different sub-issue is also challenging.

But the court cases were frequently problematic. Courts will decide things without saying explicitly what facts they relied on to come to that conclusion, making the cases more or less useless for automating legal services. Some of the cases came to clear but inconsistent opinions about which factors were and were not relevant to which sub-issues, leaving me to pick something that makes sense to them. Cases would mention factors, mention conclusions, but not mention which factors led to which conclusions. Some cases disagreed about whether a given factor should be considered for or against the conclusion, or whether it had any real significance at all.

A lot of these problems are the very same problems that lawyers have when trying to answer these questions, and not news in that sense. But combining all of those factors with the technicalities of how the analogical reasoning algorithm works requires careful consideration.

One problem that I did not anticipate was the problem of audience. I decided that my tool would have to be aimed at the people who are in the relationship that they are asking about. The reason for that is that the factors that I was generating were generated from court cases in which the people who were a part of the relationship had provided sworn testimony.

If this tool had been aimed, for example, at allowing staff of a hospital to determine whether or not a person was the nearest living relative of a person who had received emergency treatment, that same list of factors would be inappropriate. A hospital staff members is not going to know, for example, whether or not the two people have traveled together, or call each other by terms of endearment.

IBP is also not perfect. It is used to determine legal issues, but the metaphor it uses is a “case.” In reality, the same issue might be decided twice in the same case, and in different ways, and on different facts. In my research, one case found that prior to a certain date the parties were not in a relationship of interdependence, and after that same date they were. That’s two decisions, not one, arising from different factors, but in the same case. How should that be encoded? How should cases decided by appeal courts be treated differently? How should more recent cases be treated differently? What if the answer to a factor in a test case is not “yes” or “no,” but “impossible to determine” or “irrelevant in this case”? All of these are things that IBP can’t clearly answer. But for all of those limitations, it seems to work extremely well in the right circumstances.

Can I Try It?

Ah! I almost forgot! Yes, of course! Here is the live demo of the tool which will predict whether you are in an adult interdependent partnership with someone in Alberta.

No, I mean I want to Install it and Build My Own!

Oh, right! Cool! Head to the Github page and check out the readme for all the details on how to install and use the finished project. If you have any problems, join the #analogyproject channel on the docassemble slack, or file an issue in Github.

Documentation and tutorials are going to be a work-in-progress into the future, but you will be able to find them from the github page.

Conclusion

The subjective question problem is no longer an obstacle to using expert systems to automate legal services. There is a realistic way around that problem, and if we keep trying, we will continue to find better and better routes.

There are other problems we need to solve before we can bring expert systems truly to bear in the access to justice realm. Perhaps the next most salient is making expert system technology user-friendly enough that lawyers want to learn it. Regulatory restrictions are another major problem. At times, forgiveness will likely need to be sought in lieu of permission.

But another thing this project has proven to me is that there is a community of lawyers out there who are passionate about bringing innovation to the legal profession in the service of justice. Smart, awesome, passionate, energetic people who are laying the groundwork for a new kind of legal profession that isn’t here yet. One that has more technology, and more humanity.

Thanks

This will be my last blog post while officially an ABA Innovation Fellow, so I’m going to impose upon you, dear reader, to thank some important people.

My sincere thanks to Kevin Ashley and Stefanie Brüninghaus for developing the IBP algorithm, and to Matthias Grabmair for the Python implementation of IBP in openlcbr on which docassemble-openlcbr is based.

Huge thanks to the American Bar Association Center for Innovation, and in particular Chase Hertel, Sarah Glassmeyer, and Joshua Furlong, who were all particularly involved in selecting my proposal.

Jack Newton, Joshua Lenon, and Chris Thompson of Clio were all instrumental in Clio deciding to sponsor my fellowship, and allowing me to expand it to the success that it turned out to be.

Because of Clio’s sponsorship I had the opportunity to expand the project from one phase to three. I also got to find out if it was possible to use data from your firm’s own practice management system in order to power an analogical reasoner in the cloud. Turns out, you sure can.

Thanks, too, to Jonathan Pyle for developing docassemble, and for his constant and expert assistance over the three months that this project was underway. I lost count the number of times Jonathan added a feature to docassemble in less than 24 hours to make this project easier.

The docassemble user community were extremely helpful and patient with a lawyer who was learning docassemble, Python, IBP, and any number of other things. Thanks to all of you.

And most importantly, a huge thanks to my wife Maja, whose unwavering support and confidence is a gift no man could deserve.