SAFE in Drools

This week I had the opportunity to spend more time playing with Drools, and I now have something that actually works. It’s not perfect, but it does generate correct answers. Let me give you a tour.

What’s SAFE?

“SAFE” is Y-Combinator’s Simple Agreement for Future Equity. It is a contract that is designed to allow an investor to buy part of your startup company, right away, without you needing to go through the hassle of issuing non-voting shares, waiting for other investors to be ready to pay, etc.

The rules that I’m encoding here are the version of the SAFE that has both discount rates and valuation caps. The contract and the user guide are available here.

What’s Drools?

Drools is a production rule system that allows you to write Java code that runs on the basis of rules. A rule, in Drools, is a combination of a condition and a conclusion. The condition can be understood as a search for data in the knowledge base, and the conclusion as a sequence of things to do with any data that is found.

What does the code look like?

Defining Ontology

Java is an object-oriented programming language, so Drools provides a way to define types of data that get implemented as class definitions in the background.

I need to give Drools a place to store information about a SAFE. Here’s the code that does that, in the current version:

declare SAFE

investor: Person

company: Company

purchase_amount: Integer

post_money_valuation_cap: Integer

discount_rate: Double

safe_result: SAFE_Result

date_terminated: Date

terminated: boolean

safe_price: Double

liquidity_price: Double

conversion_price: Double

conversion_amount: Double

cash_out_amount: Integer

terminating_event: RWEvent

end

You can see that I’m referring to a few other types that I have defined similarly, such as RWEvent (which stands for Real-World Event), Person, Company, and SAFE_Result, which is a structure that holds useful information about who is obliged to do what when the SAFE terminates.

Encoding Rules

Some of the language in the SAFE is then written in Drools. For instance, the contract says this about equity financing:

S 1 (a) Equity Financing. If there is an Equity Financing before the termination of this Safe, on the initial closing of such Equity Financing, this Safe will automatically convert into the number of shares of Safe Preferred Stock equal to the Purchase Amount divided by the Conversion Price. In connection with the automatic conversion of this Safe into shares of Safe Preferred Stock, the Investor will execute and deliver to the Company all of the transaction documents related to the Equity Financing…

That rule gets implemented as follows:

rule "Equity Financing"

agenda-group "terminate"

when

s : SAFE( terminated == false,

pa: purchase_amount,

cp : conversion_price )

c : Company( ) from s.company

e : RWEvent( safe_type == SAFE_Event_Type.EQUITY_FINANCING )

from c.events

then

SAFE_Result safe_result = new SAFE_Result();

safe_result.setSafe_preferred_stock_due((int)(pa/cp));

safe_result.setInvestor_provides_documents(true);

insert( safe_result );

modify( s ) {

setSafe_result(safe_result),

setTerminated(true),

setTerminating_event(e)

}

end

The Drools rule, read in English, might be read this way:

“There is a rule called equity financing, that should be triggered only during the terminate phase. It should trigger whenever there is an unterminated SAFE, with a purchase amount and conversion price, and there is a company associated with that SAFE, and there is a real world event associated with that company, which event is an Equity Finance event. If those conditions are met, then create a new Safe Result object, calculate the preferred stock due as the purchase amount divided by the conversion price, and require the investor to provide documents. Then modify the safe found above giving it this safe result, terminating it, and recording the equity financing as the terminating event.”

It is by no means a word-for-word translation. The Drools rule needs to worry about how concepts are represented digitally, and be explicit about relationships in a way the natural language rule doesn’t need to. But you can see how there is a pretty strong 1-to-1 relationship between the rule and the code.

Adding Data

In order to know if it’s working the way we want it to, we need to give it some inputs and see what it spits out. So we need to describe a fact scenario and insert that information into the knowledge base.

Here, I used the fact scenario from Appendix II of the Safe User Guide, which involves two investors, A and B, who have both invested in a company ABC Inc., at different amounts and different valuations. Then, an equity financing event occurs, and the company has increased in value to $15M.

I could have written the code in Java, but it was more convenient to write a rule that triggered first, and enter the information that way. Here’s what that rule looks like:

// Rule to Create Data For Testing

rule "Test Scenario"

agenda-group "start"

when

// Left empty so rule will always trigger.

then

Person investor_a = new Person();

investor_a.setName("Investor A");

Person investor_b = new Person();

investor_b.setName("Investor B");

Company company = new Company();

company.setName("ABC Inc.");

ArrayList<RWEvent> events = new ArrayList<RWEvent>();

company.setEvents(events);

SAFE investor_a_safe = new SAFE();

investor_a_safe.setInvestor(investor_a);

investor_a_safe.setCompany(company);

investor_a_safe.setPurchase_amount(200000);

investor_a_safe.setPost_money_valuation_cap(4000000);

investor_a_safe.setDiscount_rate(1.0);

SAFE investor_b_safe = new SAFE();

investor_b_safe.setInvestor(investor_b);

investor_b_safe.setCompany(company);

investor_b_safe.setPurchase_amount(800000);

investor_b_safe.setPost_money_valuation_cap(8000000);

investor_b_safe.setDiscount_rate(1.0);

company.setPreferred_share_price(1.1144);

company.setCapital_stock_issued(9250000);

company.setIssued_options(300000);

company.setPromised_options(350000);

company.setUnissued_options(100000);

RWEvent event = new RWEvent();

event.setType(RWEvent_Type.BONA_FIDE_TRANSACTION);

company.getEvents().add(event);

insert(company);

insert(investor_a_safe);

insert(investor_b_safe);

insert(event);

end

For those of you who have written Java before, you may be thinking that this is basically just Java code, and you’d be basically right. Rule conclusions in Drools are Java code, with a little syntactic sugar and Drools-specific functions for updating the knowledge base, like insert().

Getting the Results

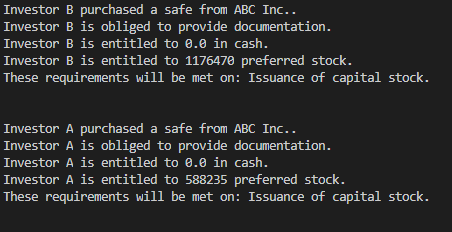

I then created a rule that would print out all of the information from the SAFE Result objects after all the other rules had triggered. When I run the code, this is the output it generates:

Investor B purchased a safe from ABC Inc..

Investor B is obliged to provide documentation.

Investor B is entitled to 0.0 in cash.

Investor B is entitled to 1176470 preferred stock.

These requirements will be met on: Issuance of capital stock.

Investor A purchased a safe from ABC Inc..

Investor A is obliged to provide documentation.

Investor A is entitled to 0.0 in cash.

Investor A is entitled to 588235 preferred stock.

These requirements will be met on: Issuance of capital stock.

Take-Aways

Forward vs. Backward Chaining

There is a lot more work that I expected in telling Drools what rules to fire, and when. That may be a result of the fact that I haven’t really taken advantage of Drools’ backward-chaining capabilities, yet. So I’m going to learn more about Drools’ ability to set out functions and queries, as distinct from rules, and see how close we can get to the contract generating its own procedure.

Risks and Benefits of Combining Declarative and Procedural Statements

Drools has a feature which, when I read about it in the documentation, surprised me. Essentially, it allows you to take two rules, and write them in one rule. I wasn’t sure what you would use that for, or why it would be better than the alternatives.

The example from the documentation looks like this:

rule "Give free parking and 10% discount to over 60 Golden customer and 5% to Silver ones"

when

$customer : Customer( age > 60 )

if ( type == "Golden" ) do[giveDiscount10]

else if ( type == "Silver" ) break[giveDiscount5]

$car : Car( owner == $customer )

then

modify($car) { setFreeParking( true ) };

then[giveDiscount10]

modify($customer) { setDiscount( 0.1 ) };

then[giveDiscount5]

modify($customer) { setDiscount( 0.05 ) };

end

What seemed strange to me is that this is a single “rule”, but it has three different sets of conditions, and three different sets of conclusions. Either the customer is not a senior, in which there is only free parking, or they are a golden senior, in which case they also get the gold discount, or they are a silver senior, in which case they also get the silver discount.

It seemed strange to me that you would want to include all of this in a single rule. Then, I came to this section of the SAFE:

(e) Termination. This Safe will automatically terminate (without relieving the Company of any obligations arising from a prior breach of or non-compliance with this Safe) immediately following the earliest to occur of: (i) the issuance of Capital Stock to the Investor pursuant to the automatic conversion of this Safe under Section 1(a); or (ii) the payment, or setting aside for payment, of amounts due the Investor pursuant to Section 1(b) or Section 1(c).

This is strangely written, because my understanding of the rest of the contract is that you cannot have a situation in which the company is entitled to convert the safe OR pay the investor. It is always one or the other, so none of them will ever be “earlier.” But still, if I read this rule to say that the termination of a SAFE occurs on one event under Section 1(a) and another event under Section 1(b) and (c), I still have a rule with two different conditions, and two different conclusions, that is drafted as a single rule.

Being able to write it as a single rule, even though it could also be written as two different rules, may be helpful to maintain the 1-to-1 relationship between the written rules and their encoding.

However, because it introduces procedural elements into the rule language, it may also serve to make the encoding harder to formally verify. Procedural language is very difficult to prove anything about. For example, with the right encoding you might have been able to automatically detect that “earlier” in the above clause can never happen.

So it seems to me now that there may be good reasons to sacrifice perfect isomorphism if you want to be able to do formal verification. And it may also make sense to have a language that combines procedural and declarative statements, and maintain isomorphism, if you aren’t worried about formal verification.

Coming Soon

Some of the junior researchers at the Centre for Computational Law have been helping me make improvements to docassemble-DADataType this week.

It is an add-on package for Docassemble that I demonstrated at Docacon 2020, that allows you to create a Docassemble interview without writing any questions, just a typed data structure.

We are currently working on adding enumerations, lists, and object references, along with more of the standard Docassemble data types.

The idea is to reduce the number of steps involved in going from (a data structure and a goal) to (a working Docassemble interview). Specifically, reducing the number of steps to zero.

Quick Notes

- Oct 29: Stanford CodeX lunch webinar on Blawx (free to join, if you’re interested)

- Nov 4: Cyberjustice Laboratory (University of Montreal) webinar on Blawx

- Nov 17: European Commission Rules as Code Blawx demo in conjunction with the OECD’s “Government After Shock” event.

- Nov 17&18: Guest lecturing for Megan Ma’s course at Sciences Po.

- Nov 24: Rules as Code session with Canada School of Public Service

I am a lawyer at Round Table Law, I teach “Coding the Law” at the University of Alberta Faculty of Law, and I’m a senior researcher at the Singapore Management University Centre for Computational Law. Computational Law Diary is a series of posts on what I’m thinking about in the computational law world. They are my own opinion, and do not reflect the opinions of the Centre, the Research Programme, SMU, U of A, or anyone else.