Progress on DADataType

This week we made some progress bringing features of top-of-the-class logic programming tools to open source.

If you are using a tool like Oracle Intelligent Advisor, or Neota Logic, for example, you can follow these steps:

- Describe the domain.

For example, you might explain to the tool that a game has two players and a winner, players throw a sign, the signs are Rock, Paper, and Scissors. - Encode the rules.

For example, you might explain to the tool that Rock beats Scissors, Scissors beats Paper, and Paper beats Rock. And you might explain that the winner of the game is the person whose sign beats the other person’s sign. - Ask a question.

For example you might ask about the winners of any games.

With those three pieces of information, and without you needing to do any interface design work, tools like OIA and Neota can generate a web-based interface that will ask the user for the required facts until it has the data it needs to answer your question.

For example, the interface may have a screen that asks “are there any games?” If there are, it will ask what the throws were of the two players in those games. And then, on the last screen, it will give the answer to the question of who won.

The questions may come in a strange order, and the interface may be less than perfectly user-friendly, but this automatically-generated interface feature allows you to rapidly prototype and test applications that are based on encoded rules, making it easier to demonstrate the value you get from encoding the rules.

The Two Problems

The two problems with the existing tools for this are that they are deeply integrated, and not open source.

Deep Integration

When I say that they are deeply integrated, what I mean is that you cannot use a non-OIA data structure or a non-OIA ruleset to generate an OIA interface. Similarly with Neota Logic. They come as a package deal. There is no ability to add Neota Logic interfaces to code that is written in a different rule language. That forces you into a specific tool in order to get those benefits.

Cost

And being forced into those tools is less than agreeable for a lot of Rules as Code and legal automation purposes, because they are closed source, and relatively expensive. (Though Neota Logic is probably roughly a degree of magnitude less expensive that OIA to deploy.)

The Ideal Solution

What would be nice is if we had a way to use open source software that was capable of generating a user interface for your expert system, and it did not care what language your rules were written in, or the language in which your domain was described.

That doesn’t exist, yet, but SMU’s Centre for Computational Law is working on it, because we would like it to be easy to generate a user interface that allows you to prototype and test applications written in L4, our programming language for law.

Breaking Down the Problem

There are two parts to the problem.

- Your interface needs to be able to know what questions to ask on the basis of the rules, the goal, and the data structure.

- Your interface needs to know how to ask any of those questions based on the data structure.

What we are working on right now is part 2.

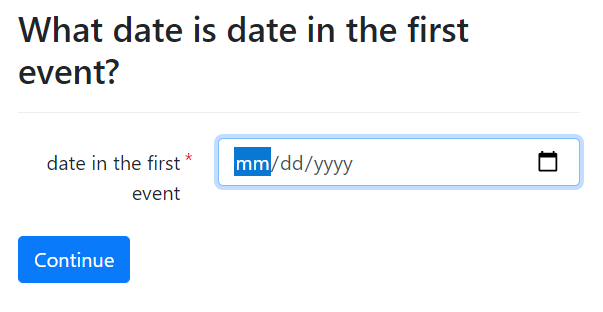

Docassemble works with Python modules and YAML interview files. Our module, docassemble-DADataType, gives you a library of Python classes that you can use to describe the data structure in your code, and a set of default interfaces for asking about those kinds of data.

The plan is to write code that will compile from our L4 language to a Docassemble package that can be imported with a single line of code in your docassemble interview, and then display questions for whatever the goal of the interview requires.

Our proof of concept is to do that translation into Python objects manually, and see what sort of interface we end up with.

What’s New in DADataType?

When we released DADataType some time ago, it only dealt with a few simple data types like numbers and text and email addresses. In order to be able to represent the types of data structures that we want to be able to represent in L4, we needed to add a few more capabilities.

Critically, the improved version of DADataType is now able to deal with more complicated forms of data structures: objects as attributes, object references, and lists.

Objects As Attributes

If in your rules a “game” is a thing that has two players, and a “player” is a thing that has a throw, then “game” is an object class, and “player” is an object class. Allowing DADataType to deal with objects as attributes means that your data structure can say “a game has player1, which is a player, and player2, which is a player.” The fact that both players have a “throw” is implicit. So your data structure, when you create a game object, will look like this:

Game1

|- Player1

| |-Throw

|- Player2

| |-Throw

|- Winner

Being able to build up these nested data structures is very helpful. If you create a game, that game will have information, inside the game, about the players and their throws.

Objects as References

The important part about objects as attributes is that the information about the players is inside the game. Sometimes, you need to answer questions like “are there any players who are in more than one game?”

For that sort of question to be answered, it is really inconvenient for the information about players to be inside the games. If it is, you are going to have to create some data element that uniquely identifies the players, make sure you enter it the same way each time you are referring to the same person, and manually add to your code that what you are checking for is whether there is a player whose identifying factor is the same in two different games. And good luck if you have two players with the same name. In order to know if the games are different, they need identifiers also.

What is far more convenient is if players are off on their own, and games just refer to them. You can think of this as the Player1 attribute of the Game object being a role, and instead of holding all the information about the Person who fills it, it just points to that information somewhere else. That’s an object as a reference.

Then it is simple to ask whether two players are the same player, or two games are the same game, without needing to give everything unique identifiers, and complicate your data structures and your queries.

Game1

|- Player1

| |- Refers to Bob

|- Player2

| |- Refers to Jane

|- Winner

Game2

|- Player1

| |- Refers to Bob

|- Player2

| |- Refers to Tim

|- Winner

Bob

|- Throw

Jane

|- Throw

Tim

|- Throw

In my experience, this sort of problem comes up all the time in legal matters. “A person cannot witness their own will,” for example, requires you to ensure that the person making the will and the person witnessing it are not the same person. Encoding that sort of rule is made a lot easier with object references.

DADataType implements two kinds of object references: pick one, or pick any. Pick one allows you to specify one object from a list, like “the person who will witness the will”. Pick any allows you to select zero or more items from a list, like “chocolate bars I like”.

Lists

DADataType has also been expanded to be capable of asking the questions required to collect a list of objects of any data type that DADataType can handle.

The Proof of Concept

We took the work that we have been doing on encoding the SAFE contract and used that as a starting point for doing our PoC. We generated the Python classes that would represent the same data structure as we used in encoding the SAFE in Drools Rule Language in a way that it would be possible to automate.

As a reminder, this is what the DRL data structure code looks like, but you could write a tool that translated from any data structure language into a DADataType package.

declare SAFE

investor: Person

company: Company

purchase_amount: Integer

post_money_valuation_cap: Integer

discount_rate: Double

safe_result: SAFE_Result

date_terminated: Date

terminated: boolean

safe_price: Double

liquidity_price: Double

conversion_price: Double

conversion_amount: Double

cash_out_amount: Integer

terminating_event: RWEvent

end

We then manually generated a Docassemble interview file that it would be possible to automatically generate from nothing other than the information above.

Then we added a goal: a final screen showing details that were collected about SAFE contracts.

Without having to describe how any of the pieces of information should be collected, we got a working Docassemble interview. Here is a video of what a test-run looked like:

The question order is a bit strange, and the wording of the questions is a bit strange, but they are all being generated automatically without any work by the developer, and it is of a quality that is comparable to the industry-leading tools listed above.

Plus, it will keep getting better. It is free, and anyone with a data definition language can very easily write code to generate a Docassemble package to generate similar interfaces.

A huge thank you to the junior researchers at the Centre who took a break from learning Haskell to help get this project moving again.

What’s Next?

We need to update the GitHub repository with the improved tool, which should happen soon. When the syntax for L4’s data structures and queries has solidified better, we will need to come back and write the code that goes from the L4 to a DADataType interview package in zero steps. We also need to write some documentation on how to name your classes and attributes so as to get the most mileage out of the way Docassemble comes up with names for things. And there are probably some tweaks that we could do to make the generated text better.

Eventually, I also anticipate that we will want to return to part 1 of the problem above, and come up with a way for Docassemble to decide what questions to ask on the basis of L4 rules, as opposed to document templates or chunks of imperative code. But that will need to wait until we have L4 code running.

Quick Notes

- Oct 29: Stanford CodeX lunch webinar on Blawx (free to join, if you’re interested)

- Nov 4: Cyberjustice Laboratory (University of Montreal) webinar on Blawx

- Nov 17: European Commission Rules as Code Blawx demo in conjunction with the OECD’s “Government After Shock” event.

- Nov 17&18: Guest lecturing for Megan Ma’s course at Sciences Po.

- Nov 24: Rules as Code session with Canada School of Public Service

I am a lawyer at Round Table Law, I teach “Coding the Law” at the University of Alberta Faculty of Law, and I’m a senior researcher at the Singapore Management University Centre for Computational Law. Computational Law Diary is a series of posts on what I’m thinking about in the computational law world. They are my own opinion, and do not reflect the opinions of the Centre, the Research Programme, SMU, U of A, or anyone else.