Getting Smarter about Time

Let’s say I’m building a web app that tells you whether or not you are allowed to drive based on whether or not you have a license. Easy. You check a box that says you have a license, and I say “yes” or “no” based on whether or not you have the license.

But you don’t always want to know about right now. Maybe you got a ticket last week, and you want to know if you were legal to drive then. Well, it depends on whether you got your license before you drove, and it didn’t expire until after you drove.

“Before” and “after” here are relationships in time. So a system that can answer questions about the past and the future needs to be able to deal with those sorts of relationships. Usually, the way you deal with them is by using dates. You might say that I got my license on January 1, and I drove the car on January 2. The system might ask the users for those dates in a nice drop-down calendar format.

That’s all well and good. It’s also basically the state of the art.

But what if the ticket was a long time ago, and the person can’t remember when they got their license? And, what if the person knows when they renewed their license, and you know that that could only have happened within 6 months of it expiring, and that it expires 5 years after it is issued.

You, as a human being, might ask “well, did you get the ticket less than 4 and a half years prior to the day you renewed?” That’s what I want to make the computer able to do. But a computer can’t do that if every piece of information about time is recorded as a specific date.

Allen a Day’s Work

That’s actually a very sophisticated behaviour, because it requires the computer to imagine what other facts might be true that could make the question possible to answer based on the uncertainty.

As a step toward those kinds of capabilities, I decided to take a crack at writing some code that would implement Allen Interval Algebra. The details of the algebra are relatively complicated, but the intuition is pretty simple.

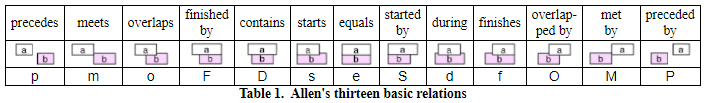

An “interval” is a period of time with a start and an end. Two intervals can relate to each other in one or more of 13 different ways, that are displayed here:

The bunch of ways that two intervals might relate to one another is called an “Allen Relationship”. Pretty much any temporal relation can be expressed using these intervals and relationships.

It’s about what you don’t know

The important thing to note here is that an Allen Relationship is all of the ways that two intervals might relate, not the ways they actually do. Allen Relationships allow you to say things about relative time, if you don’t know exactly when the events in question occurred.

Indeed, if there are two intervals and you know absolutely nothing about their relationship in time, what you would have is a relationship where all 13 relations are possible.

For example, in the case of the driver’s license, there would be an interval during which the license was valid, an interval during which it was possible to renew, the date the person renewed, and the date they got their ticket. You don’t need to know the date they got their license in order to determine the only thing that matters, that they got the license before the ticket, or that they got the ticket during the time they had a valid license.

A Quick Example

Let’s take an example from Rock, Paper, Scissors. Let’s say that the process involved is this:

- the game starts

- the players count

- player 1 throws,

- player 2 throws,

- player 1 sees what player2 has thrown,

- player 2 sees what player 1 has thrown, and

- the game ends

That’s sort of informal. We need to break it out into intervals, and relationships. Here are some things that we know about the time relationships between the different intervals:

- the throws and the count happen during the game.

- each player throws before they see what the other player has thrown

- each player sees what the other has thrown after they throw it

Eventually these intervals and relationships could be automatically generated when you use keywords in a domain specific programming language for law like

BEFORE,UNTIL, orNOT DURING. That sort of language what we’re working on at SMU Centre for Computational Law.

Now, even though I haven’t told the system anything about the relationship in time between the counting and player 2 seeing player 1’s throw directly, I can ask it to figure it out, by following the chain of links from the players counting, to player 1 throwing (l8),and from player 1 throwing to player 2 seeing (l6).

flora2 ?-

l8[relationship->?_step1],

l6[relationship->?_step2],

?_step1[composition(?_step2)->?_answer[display]].

p

Times (in seconds): elapsed = 0.010; pure CPU = 0.000

Yes

And the answer to the question is ‘p’ for “precedes”. Which means the counting must have finished some time before the start of the interval during which player 2 saw player 1’s throw.

If you’re interested in taking a look at the code, it’s on GitHub.

Next Steps

I need to write some code that finds the strongest possible temporal relationship between two intervals based on all the relationships in the database. Then I need to see how I can modify the events and actions model I’m using in my SAFE encoding to say things like “first the investor must sign the documents, and after they are signed the investor must deliver them” without requiring the user to specify dates in order to determine whether or not that happened. If they receive a signed document, they know it was signed before they received it. The dates don’t matter.

Quick Notes

- Nov 17: European Commission Rules as Code Blawx demo in conjunction with the OECD’s “Government After Shock” event.

- Nov 17&18: Guest lecturing for Megan Ma’s course at Sciences Po.

- Nov 24: “Rules as Code” session with Canada School of Public Service.

- Jan 12–14: Presenting on Blawx at the Legal Services Corporation Innovations in Technology (Virtual) Conference.

- TBD (Jan ’21): Cyberjustice Laboratory (University of Montreal) webinar on Blawx.