Explainable Event Calculus in Carneades

If you’ve been following along for the last few weeks, you know that I’ve been playing with different methods of representing event calculus, and aiming at being able to explain the outcomes.

This week I’d like to show you an experiment I did with a tool called Carneades. Carneades is named for the ancient Greek philosopher who was famous for having travelled to Rome and given two lectures in two days. The first lecture was for the existence of justice, and the second lecture was against it.

Carneades believed that wisdom came from being able to argue both sides of an issue. Carneades the tool is well-named, because it is a tool for argumentation theory, which is the theory of how we represent and reason about arguments, as opposed to deductive rules.

Carneades is a piece of software that is designed to help you write, test, and find arguments. I’m not so interested in writing arguments. But I am very interested in finding them, and testing them.

Why?

An argument and an explanation are two names for the same thing.

A piece of software that can generate a compelling argument for its conclusion is a piece of software that can explain its conclusion. And a potentially compelling explanation if the elements of its argument are objectively verifiable, like sections of legislation and agreed facts.

What is an Argument Scheme?

Carneades allows you to set out something called an “argument scheme”. Delightfully, the language for writing Carneades code is just YAML! This is what an argument scheme might looks like:

argument_schemes:

- id: mortal_if_human

variables: [X]

conclusions:

- mortal(X)

premises:

- human(X)

Hopefully the content will be familiar.

An argument scheme is a pattern that Carneades can use to build specific arguments, like, for example, the argument that Socrates is mortal because Socrates is human, by replacing X with Socrates.

So it looks kind of like what we think of as a rule. And behaves very much like one, too.

But importantly, Carneades is focused entirely on analysing the arguments, not just finding the answers. So the output is not an answer, like mortal(Socrates). Instead, the answer is a network of arguments.

Let me show you a toy example:

language:

human/1: "%s is human."

mortal/1: "%s is mortal."

immortal/1: "%s is immortal."

socrates/0: "Socrates"

issue_schemes:

mortality:

- mortal(X)

- immortal(X)

argument_schemes:

- id: mortal_if_human

variables: [X]

premises:

- human(X)

conclusions:

- mortal(X)

exceptions:

- immortal(X)

assumptions:

- human(socrates)

So what’s happening here? Carneades is being given a language of predicates, and a way to express those predicates in natural language. It is also given a way to make grounded statements without variables. So it knows how to say what you are asking about.

Then you tell it what “argument” (as in ‘debate’) you are having. Here, we are having an argument in which the two sides of the argument are either Socrates is mortal, or he is not.

Then we tell Carneades about a kind of argument (as in ‘reason’)that is acceptable in this argument (as in ‘debate’), and that is the rule that a thing is mortal if it is human, unless we know it is immortal.

Then we tell Carneades what we know about the situation, that Socrates is human.

Reading Carneades Argument Graphs

If you save the above text to a file, and then go to this link, you can load that file into the Carneades tool, and get this back:

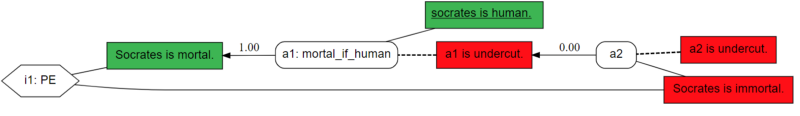

This is an argument graph. Reading these took me a while to sort out, but here’s the short version: A hexagon is an issue, and is connected by lines to the positions in that issue. Positions (or facts, or conclusions) appear as boxes. The box is green if it is supportable. It is red if it not supported.

An argument is depicted as a white oval, and is connected by an arrow to the conclusion that it either supports or fails to support. (Remember, Carneades is going to show you good AND bad arguments.) That arrow has a weight between 0 and 1, because Carneades allows you to give different arguments different weights, and then determine which argument was most persuasive according to some weighting formula. If the arrow has a weight of 1, the argument is proof of the conclusion. An argument is connected by solid lines to the facts that were premises of the argument, and by dotted lines to any premises that would not not have supported it, but instead defeated or undercut it.

So we can see that we have one issue, and the issue is whether or not Socrates is mortal. The positions are that “Socrates is mortal” and that “Socrates is immortal”. We can see that Socrates is mortal is green, which means it is supported. Socrates is immortal is red, which means that it is not supported. The fact that there are no arguments to the right of it suggest that there was not even an argument to be made that Socrates was mortal.

The fact that Socrates is mortal is supported by the argument “a1”, which was found by Carneades, using the “mortal if human” argument scheme. The premises of that argument are just that socrates is human, which is green, because that was an assumption. That argument might have been undercut (but was not, because the undercut is red), by an argument Carneades found which it called “a2”, the premise of which is that Socrates is immortal, which again, there was no reason to believe. The second argument A2 could also have been undercut, but there was no reason to believe that it had been undercut.

Why is Argumentation Theory Useful in Law?

There are a few reasons that the Carneades approach seems particularly useful in law. One is that it does not limit itself to finding a single argument for a conclusion. In law, you might be interested in finding multiple valid arguments for the same conclusion, or finding multiple arguments against one.

Most deductive reasoning tools will be perfectly happy to tell you how they came to their conclusion, but they are not as good at telling you how else you might have reached the same conclusion.

Event Calculus in Carneades

But, of course, I’m playing with event calculus and explanations, and so I’m curious whether it’s possible to “teach” event calculus to Carneades, and then give it a fact scenario, and have it determine the answers to that question, and explain them.

Turns out… yeah. It’ll do that.

meta:

title: Event Calculus Example

notes: >

Illustrates deriving an argument from the axioms of basic event calculus

language:

stoppedIn/3: "after %v the condition %v started, before %v."

startedIn/3: "after %v the condition %v started, before %v."

terminates/3: "the event %v terminated the conditon %v at time %v."

happens/2: "the event %v happened at time %v."

initiates/3: "the event %v initiated the condition %v at time %v."

releases/3: "something releases %v %v %v."

trajectory/4: "something trajectory %v %v %v %v."

antiTrajectory/4: "something antitrajectory %v %v %v %v."

initiallyN/1: "initially, the condition %v is not true."

initiallyP/1: "initially, the condition %v is true."

lt/2: "%v is less than %v"

holdsAt/2: "condition %v is true at time %v."

notHoldsAt/2: "condition %v is false at time %v."

argument_schemes:

- id: stopped_if_terminated

variables: [T,E,T1,F,T2]

conclusions:

- stoppedIn(T1,F,T2)

premises:

- lt(T1,T)

- lt(T,T2)

- terminates(E,F,T)

- happens(E,T)

- id: stopped_if_released

variables: [T,E,T1,F,T2]

conclusions:

- stoppedIn(T1,F,T2)

premises:

- lt(T1,T)

- lt(T,T2)

- releases(E,F,T)

- happens(E,T)

- id: started_if_initiated

variables: [E,T,T1,F,T2]

conclusions:

- startedIn(T1,F,T2)

premises:

- lt(T1,T)

- lt(T,T2)

- initiates(E,F,T)

- happens(E,T)

- id: started_if_released

variables: [E,T,T1,F,T2]

conclusions:

- startedIn(T1,F,T2)

premises:

- lt(T1,T)

- lt(T,T2)

- releases(E,F,T)

- happens(E,T)

- id: holds_if_trajectory

variables: [F1,F2,T1,T2,E]

conclusions:

- holdsAt(F2,T2)

premises:

- initiates(E,F1,T1)

- happens(E,T1)

- trajectory(F1,T1,F2,T2)

exceptions:

- stoppedIn(T1,F1,T2)

- id: holds_if_initially_true

variables: [F,T]

conclusions:

- holdsAt(F,T)

premises:

- lt(0,T)

- initiallyP(F)

exceptions:

- stoppedIn(0,F,T)

- id: does_not_hold_if_initially_false

variables: [F,T]

conclusions:

- notHoldsAt(F,T)

premises:

- lt(0,T)

- initiallyN(F)

exceptions:

- startedIn(0,F,T)

- id: holds_if_initiated

variables: [E,F,T,T1]

conclusions:

- holdsAt(F,T)

premises:

- lt(T1,T)

- initiates(E,F,T1)

- happens(E,T1)

exceptions:

- stoppedIn(T1,F,T)

- id: does_not_hold_if_terminated

variables: [F,T,T1,E]

conclusions:

- notHoldsAt(F,T)

premises:

- lt(T1,T)

- terminates(E,F,T1)

- happens(E,T1)

exceptions:

- startedIn(T1,F,T)

That is the basic event calculus that I wrote about last week, but written in Carneades argument schemes. You can see that I’m cheating a little bit and using a custom predicate lt/2 instead of <, because I couldn’t figure out how to get mathematical comparisons to work. I’m not even sure if it’s a feature of Carneades. So I manually set out the less-than relations between the numbers 0 and 5 in the assumptions. That’s a weakness of Carneades that I’m hoping there is an easy way to solve, or I’m just missing something obvious.

It’s also a bit frustrating that you have to use arguments to predicates in the order that they appear. You can see that has left some of my natural language expressions a bit awkward. That, too, seems like something that it would be easy to fix.

And fix it we can, because Carneades is open source.

Now that we have explained event calculus, we are going to re-encode our work-from-home regulation, in event calculus, in Carneades. Here’s what that looks like:

statements:

initiates(wfh_order, wfh_required, 1): A work from home order requires you to work from home.

terminates(presence_required, wfh_required, 3): A presence required notice requires you to go in to work.

initiallyN(wfh_required): Initially, work from home was not required.

happens(wfh_order, 1): A work from home order was issued at time 1.

happens(presence_required, 3): A presence required notice was sent at time 3.

assumptions:

- initiates(wfh_order,wfh_required,1)

- terminates(presence_required,wfh_required,3)

- initiallyN(wfh_required)

- happens(wfh_order,1)

- happens(presence_required,3)

The need for including “statements” can be avoided if you add the atoms like wfh_order to your language. But they give you the option of reformulating how specific things will be said.

Wehave the same event calculus pattern as last week. Initially, work from home is not required. Then at time 1, a work from home order is issued, which initiates the requirement to work from home. Then at time 4, a presence required notice is issued, which terminates the work from home requirement.

You will note that in these assumptions, I’m saying explicitly the times at which events initiate and terminate things. Usually, in event calculus, the time would be left as a variable. I’m doing that because an assumption cannot have variables in Carneades.

We could probably add an argument scheme that allows you to derive that an initiation can happen at any time. Or, you could generate the relevant derivable facts in whatever tool you are using to answer the question, and then put those facts into Carneades to explain them. It doesn’t seem a fatal flaw.

Now we need to tell Carneades what question we want answered. We do that by setting out an “issue scheme” which is similar to an argument scheme in that it can include variables. Our issue scheme looks like this:

issue_schemes:

wfh:

- holdsAt(wfh_required,T)

- notHoldsAt(wfh_required,T)

So we are saying that the issue we want arguments for is that there are times at which working from home is required, or it is not.

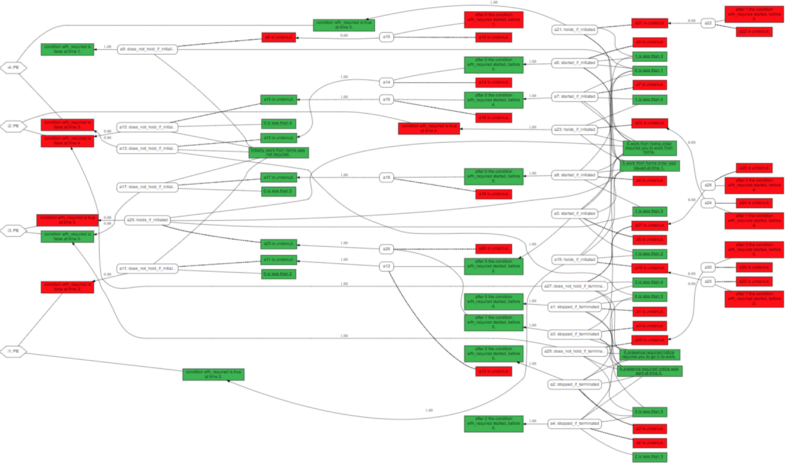

If you put that code into the Carneades online demo, and ask it for a SVG output, you get something that looks like this:

That’s a lot of stuff. Each of the arguments corresponds either to an axiom of event calculus, or an exception to one of them. It successfully determines that working from home is not required at time 1, is required at times 2 and 3, and not required again at time 4 and 5. Actually, it treats only the last four as “issues”, because it cannot find any argument that work from home would be required at time 1. If there is no counter-argument, there is no issue.

Strangely, the box that indicates that you don’t need to work from home at time 4 appears red in the graph, despite the fact the only argument supporting it is green, and has been given a weight of 1. If you look at the YAML version of the output, you can see that it determines the work from home is not required at 4, so there seems to be a bug in the code that generates the SVG graphics. I let the maintainers know.

If you’re interested in playing with it, the code for the above diagram has been submitted as a pull request to be added to the examples in the Carneades4 project on GitHub.

OK, but what would you DO with it?

This looks like a bit of a mess. But it is actually a very interesting resource from the perspective of Explainable AI. Because this data is able to answer questions like “why is work from home required at time 2?” But it is also able to answer questions like “why is it not true that work from home is not required at time 3?” That sounds like a double negative, but the arguments for work from home not being required in event calculus are different from the ones that make it required. The same could be true about a legal situation. The laws that make you divorced and not the same laws that make you married.

Also, because this includes some arguments that have been given a weight of zero, it can be used to explain why certain arguments are bad. For instance, you could ask “isn’t there an exception to the rule that makes work from home required at time 2?” And your software, just by navigating this tree, could say yes, tell you what the exception was, and then tell you why it didn’t hold.

As for the explanations that we built last week with s(CASP), you could build those from this tree, too, just by printing out the elements of the tree that were expressed in the event calculus, only.

So the graph is hard to read, but it includes a lot of useful information that can be displayed differently, and will give the users a coherent explanation for an automatically-generated conclusion.

A Wild Idea

Interestingly, if you had a model of the domain that could be put into Carneades, it might be possible to use Carneades to generate explanations for systems that can’t explain their own decision-making. And in so doing, impose restrictions on the kinds of answers that black-box systems are allowed to give.

That is to say, generate a model in Carneades that accepts the same factors and gives an explanation for the conclusion, but then reject the explanation and the conclusion if the explanation is not sufficiently strong.

In that way, the addition of argumentation theory to machine learning might provide a way to both enhance the usefulness of the technology in law, and reduce its risks. The problem would be trying to generate the model of the domain that could be verified by human beings and encoded in a tool like Carneades without just requiring human beings to write the entire thing from scratch. Getting an algorithm to describe itself in a way that could be converted into “argument schemes” would be a huge step forward.

Quick Notes

In January I will be speaking at CyberJustice Lab in Montreal, and also at the LSC ITC Conference. In March, I will be doing a presentation on Rules as Code at the ABA TechShow!