Encoding Covid-19 rules using Basic Event Calculus in s(CASP)

Alright, fellow legal nerds, let’s get deep in the weeds, here.

What is Event Calculus?

A “calculus” is a way of reasoning about something. Event Calculus is a way of reasoning about events, and their consequences. I use consequences here to mean “what happens after those events have occured, and because those events have occurred.” So it is a calculus of causes, and a calculus of time.

What is Discrete Event Calculus?

There are a bunch of different varieties of Event Calculus, or EC. One variety is discrete event calculus. The difference between regular event calculus and discrete event calculus is that discrete event calculus treats moments in time as being discrete points. In essence, you can say that the time of an event is 1, or you can say that it is 2, but you cannot say that it was 1.5. Maybe the numbers refer to seconds, maybe they refer to years, it doesn’t matter. The point is that whatever level of precision you choose, you can’t go below it any longer.

Why is that useful? Well, if you have two events, and the amount of time that passes between them is 1, you no longer need to check for any intervening events. Because there can’t be any. That makes the algorithm for solving event calculus questions faster. But it also limits the kinds of problems you can solve with it. Sometimes the trade-off is worth it, other times not.

What is Basic Event Calculus?

The authors of s(CASP) wrote a paper in which they demonstrated how it can be used to automate reasoning in event calculus, but the version of event calculus that they implemented was simplified. They refer to it in the code as basic event calculus or BEC. So that’s what I’m calling it.

I decided to try and see if I could re-implement the covid rules I implemented in the last post using basic event calculus.

Encoding Covid Rules in Event Calculus

The Basics: Events and “Fluents”

In order to encode that rule in BEC, we need to model it in the sorts of concepts that BEC knows about. Those are events, and something called “fluents”.

An event is intuitive. It is a type of thing that happens at a specific point in time.

A “fluent” is a thing that may or may not be true at a given point in time, depending on which events have occurred.

The Common Sense Rules: Initiates, Terminates, Trajectory, and Anti-Trajectory

Once you have a set of fluents and a set of events, you need to explain how they interact with one another. That is done by saying which events initiate which fluents, and which events terminate which fluents.

If you want to say that an event has a consequence, but not immediately, there is a way of specifying when the thing will happen called a trajectory. If it causes a fluent to initiate, it is a trajectory, and if it causes a fluent to terminate, it is an anti-trajectory.

Those four ideas, in combination with all of the rules of logic (implications, conjunction, disjunction, etc.), allow you to say things like “the flipping the switch event causes the light to be on if the light was off and there is power to the house or the generator is running”, and “the flipping the switch event causes the light to be off if the light was on.”

The Facts: Initially, and Happens

Once you have set up a set of events and fluents, and you have explained how they interact with one another, you need to set out two additional things. If you want to say whether fluents were true or false initially, you use initially. If you want to say what happened later, you use happens.

The Question: HoldsAt

Now the computer knows what the start condition was, and it knows what happened. It knows what the consequences of those events are, and it can calculate what fluents were true or false at any given time, which is what you are using the event calculus to find out. So to find out, you ask whether or not a fluent “holds” (is true) at a specific time.

Encoding Covid Rules in Event Calculus with s(CASP)

So you may remember that our rule was as follows:

Working from home is mandatory unless the employer requires a physical presence for operational effectiveness.

Step 1: Events and Fluents

The first thing we need to do is model this rule as a set of events that happen, and things that may or may not be true. For this simple example, we will say that there are only two things that can happen. A work from home order can be imposed, and a person can be designated as being required to work in person. We will call these wfh_ordered and presence_required. The only fluent we are interested in is whether or not someone is required to work from home, which we will call wfh_required.

That’s obviously simplified, but this is a demo. Note also that for the sake of simplicity we’re not building a tool that is able to answer different questions for different people. Our model assumes that there is only one person we would be interested in asking about.

Step 2: The Rules

The relationship between the events and the fluents is pretty straightforward. A person is required to work from home once a work from home order has been issued, until and unless they have been told their presence is required for operational effectiveness.

So we need to say that a work from home order initiates the requirement, and a presence required order terminates it. Here’s what that looks like in code:

initiates(wfh_order,wfh_required,T).

terminates(presence_required,wfh_required,T).

The T in those statements refers to the time. By using T instead of a specific numerical value for a time, we are saying “no matter what time it is, if the work from home order is issued at a time, being required to work from home becomes true at the same time.” If you wanted to be more specific, you could.

Step 3: The Facts

What we want to say is that initially, people were not requried to work from home, and then at time 1, a work from home order was issued, and then at time 3, the person was designated as required to be present. Here’s what that code looks like:

initiallyN(wfh_required).

happens(wfh_order, 1).

happens(presence_required, 3).

The predicate initiallyN is used to describe things that are not true initially.

Step 4: The Questions

What we are hoping is that if we ask whether or not the person is required to work from home at time 0, the answer will be no. The answer at time 1 and 2 should be yes. The answer at time 3 and higher should be no.

s(CASP) allows us to ask those questions specifically, but it also allows us to ask the question “at what times is it true that the person is required to work from home?” That question looks like this:

?- holdsAt(wfh_required,T).

Unfortunately, what we would like to get as an answer to that question is the range 1–2. What we get instead is the range “greater than 1”. Why is that?

Well, Arias’ encoding divides “holds” and “not holds” into to different questions. So the answer to when the work from home requirement ends is answered by saying when the not work from home requirement begins.

If you ask both questions, you get the following answers:

- Not required to work from home: Greater than 0, and greater than 3.

- Required to work from home: Greater than 1.

If you combine those two sets of answers, you get the info you want: The person is required to work from home between 1 and 2.

Using s(CASP) Explanations in Event Calculus

For each of the answers, you can get the reasons. For example, the person is not required to work from home at or after time 3. Why?

I added some code to Arias’ encoding of the basic event calculus to give it the ability to explain itself in natural language, just in terms of the event calculus itself. I gave it a way to explain what “holdsAt” means, and “initially” means, without regard to the specific meaning of the events and the fluents. So this is a generic explanation method, not a domain-specific one.

Using that generic explanation method, here’s the answer it gave:

wfh_required was not true at time A greater than 3, because

- the event presence_required caused the status wfh_required to terminate at time 3, and

- the event presence_required happened at time 3, and

- there is no evidence that wfh_required was initiated between time 3 and time A greater than 3.

This shows a lot of promise, and a lot of problems.

The Promise

Because s(CASP) is a constraint programming tool, it is perfectly happy to reason about things like “time A greater than 3”, which means “any time after 3”. That is great, because saying “3, 4, 5…” infinitely is not the same thing, and it is not how people think about such things. So the answer is more concise, and meaningful, and it can be explained in terms that are meaningful to people.

It is also possible to generate explanations using event calculus in order to explain the individual “model” (e.g. after 3) that satisfies the question “when am I not required to work from home?” And the explanation is mostly coherent. Plus we can generate those explanations with zero additional work from the user, which is nice.

The Problems

“Why am I not required to work from home after time 3” is not the sort of question that a person is likely to ask. The sort of question they are likely to ask would be “when am I required to work from home, when am I not required to work from home, and why?” The human-friendly answer to that would be “you are not required at time 0, because that is the default. You are required at time 1, because of the work from home order. You are no longer required at time 3, because you were advised your presence was required.”

Note that if we ran the two queries, took the three answers, and put their explanations together, it doesn’t read that way.

wfh_required was not true at time A greater than 0, because

- wfh_required is not initially true, and

- there is no evidence that wfh_required was initiated between time 0 and time A greater than 0.

wfh_required was true at time A greater than 1, because

- the event wfh_order caused the status wfh_required to begin at time 1, and

- the event wfh_order happened at time 1, and

- there is no evidence that wfh_required was terminated between time 1 and time A greater than 1.

wfh_required was not true at time A greater than 3, because

- the event presence_required caused the status wfh_required to terminate at time 3, and

- the event presence_required happened at time 3, and

- there is no evidence that wfh_required was initiated between time 3 and time A greater than 3.

So we have two different problems. One is that we are not able to ask the question we want to ask, which is “tell me everything you know about when this fluent is true and false.” But we’ll come back to that problem. The more immediate issue is that the explanations for each part of the answer to the large question seem ‘inhuman.’

The first reason why is that event calculus itself is an attempt to model inside the computer things that are almost never worth explicitly saying to a human being. Things that are implicit to a human need to be made explicit for the computer, and the computer doesn’t know which is which.

For instance, saying “there is no evidence that wfh_required was initiated between time 3 and time A greater than 3” is strange. If you phrased it in a more human way, it might be “and nothing else important happened after that.” And when you think of it that way, it becomes clear that a human being would just avoid saying it altogether.

Lukcily, s(CASP) helpfully gives us the option of reducing the explanations to focus only on the things that were true in the explanation, and leave out the things that were not found, by using the --pos command. If we use that feature, this is what the explanation looks like:

wfh_required was not true at time A greater than 0, because

- wfh_required is not initially true.

wfh_required was true at time A greater than 1, because

- the event wfh_order caused the status wfh_required to begin at time 1, and

- the event wfh_order happened at time 1.

wfh_required was not true at time A greater than 3, because

- the event presence_required caused the status wfh_required to terminate at time 3, and

- the event presence_required happened at time 3.

That’s better. But we have more problems. The third answer has two sub-parts. The second one, “the event presence_required happened at time 3” makes perfect sense, and is correct. The first one, “the event presence_required caused the status wfh_required to terminate at time 3” is incorrect. It is true only about the specific model that the explanation is covering, which is the model in which the time is 3 or more. The true statement is that a work from home order always causes the requirement to be true. That’s what we said. But that fact is not stated in the explanation because of how the variables are unified.

What we could do to solve that problem is being writing some domain-specific natural language explanations, and see if s(CASP) will allow us to override the general explanations for event calculus with more specific explanation for the domain we are writing about.

For example, we might give this predicate command:

#pred initiates(wfh_order,wfh_required,T) :: 'a work from home order makes working from home mandatory'.

Note that we didn’t use the T anywhere in the explanation, so despite the fact the inference may be referring to a specific time, the explanation won’t. If we rerun the commands, this is what we get for the first question:

wfh_required was true at time A greater than 1, because

- a work from home order makes working from home mandatory, and

- the event wfh_order happened at time 1.

That’s promising. We get a better output for the third question, and we can see that it used the more specific #pred command where it found one. We could now add a natural language phrase to the terminates statement, like this:

#pred terminates(presence_required,wfh_required,T) :: 'being advised that your presence is required terminates the requirement to work from home').

Now we get this output:

wfh_required was not true at time A greater than 0, because

- wfh_required is not initially true.

wfh_required was true at time A greater than 1, because

- a work from home order makes working from home mandatory, and

- the event wfh_order happened at time 1.

wfh_required was not true at time A greater than 3, because

- being advised that your presence is required terminates the requirement to work from home, and

- the event presence_required happened at time 3.

We are getting closer. But now we have the problem that our friendly natural language explanations are being used for initiates and terminates but not for holdsAt, and happens, or initially. Because BEC treats holdsAt and -holdsAt as two different things, we need five more lines of code:

#pred holdsAt(wfh_required,T) :: 'you are required to work from home at time @{T}'.

#pred -holdsAt(wfh_required,T) :: 'you are not required to work from home at time @{T}'.

#pred initiallyN(wfh_required) :: 'you were not required to work from home initially'.

#pred happens(wfh_order,T) :: 'a work from home order was issued at time @(T)'.

#pred happens(presence_required,T) :: 'you were advised that your presence was required at work at time @(T)'.

Now if we try it again, we get the following:

you are not required to work from home at time A greater than 0, because

- you were not required to work from home initially.

you are required to work from home at time A greater than 1, because

- a work from home order makes working from home mandatory, and

- a work from home order was issued at time 1.

you are not required to work from home at time A greater than 3, because

- being advised that your presence is required terminates the requirement to work from home, and

- you were advised your presence was required at work at time 3.

That is actually really close to what a human would say. And it is certainly understandable. There are still some issues that if “time 2” is in the past, the user might expect the explanation to use the past tense instead of the present tense. But it is a step in the right direction.

We still don’t have exactly what we want, though, because we are getting three answers to two questions, instead of one answer to one question. The one question we would be interested in is when did the value of the fluent change?

We can write a simple predicate that will ask the two questions at once, and the three models will be returned as answers to the same question.

fluent_changed(F,T) :- holdsAt(F,T).

fluent_changed(F,T) :- -holdsAt(F,T).

Now we change the query at the bottom of our code to be:

?- fluent_changed(wfh_required,T).

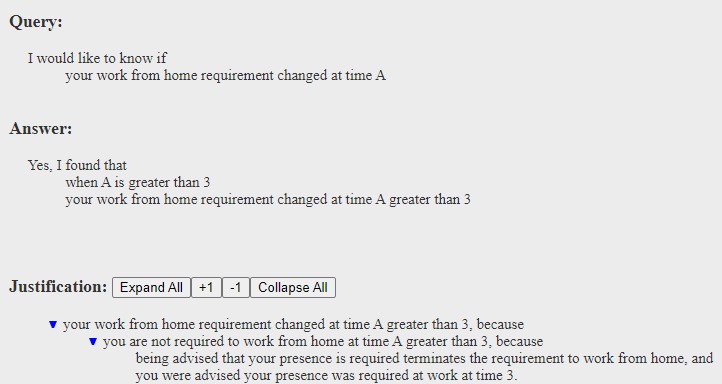

It’s not quite one answer for one question, but three answers to one question is a step in the right direction. Unfortunately, s(CASP) cannot generate web pages that given an explanation for more than one model at a time, so we can’t easily get a single web page with three answers and explanations for all three, quite yet. I’ll post the image below. Note how the explanation makes less sense out of context, because there is no explanation for why you were required to work from home prior to time 3.

What Did We Learn?

At SMU Centre for Computational Law, we’re looking to build domain specific programming languages for legal purposes. Explanations are a major requirement for such languages. Another major requirement is the ability to do different types of reasoning. For example, you may want to give it a set of facts and ask it what the current obligations are. That would be deductive logic. But maybe you want someone to be obliged to do something, and you want to give the software a set of known facts, and a desired outcome, and then ask it to generate a plan to make that happen. That is abductive logic, like planning or path-finding.

Event Calculus is one way of being able to express what a human being understands about a scenario, and have the computer be able to reason about that knowledge in multiple ways.

So it’s useful for us to look at what the user experience is of using event calculus when you want to generate explanations from the results. What I have gained is a couple of more specific questions for designing L4.

Where Does This Stuff Go?

One of the things that this experiment has raised for me as a question for our development process is “where do we want to put all this stuff”?

Some programming languages require you to declare things like events and fluents before you use them. You may have noticed that s(CASP) does not require that. But the effect of not requiring a declaration is that you don’t really have a natural place to put the natural language versions for things like holdsAt and initially. Requiring declarations might help more than it hurts by giving those things a place to belong in the code.

How Do We Make This As Easy As Possible?

Last post, I used s(CASP) without using the event calculus code, to generate explanations for a simple rule, expressed like this:

wfh_mandatory(X) :-

worker(X),

not presence_required(X).

That rule means that working from home is mandatory if you are a worker, and your presence has not been required at work.

That is a simpler model of the same rule. It doesn’t account for the possibility that I am required, but I haven’t been told that yet. And it doesn’t deal with how the facts might have changed over time.

The new model, which has two events and one fluent, is written like this:

initiates(wfh_order,wfh_required,T).

terminates(presence_required,wfh_required,T).

initiallyN(wfh_required).

You could argue that the initiallyN statement there is not a rule, but a fact. But it is implicit in the first version above that if you know nothing about Jason other than that he exists, you still know that he is not required to work from home. In order to get that same effect in event calculus, you need to set the initial states of the fluents.

That is the same number of lines of code, at 3, but more than three times as much typing in the second version. And I would argue the second version is harder to read.

The first version has three predicates that need to be explained in order for the answers to make sense.

#pred worker(X) :: '@(X) is a worker'.

#pred presence_required(X) :: '@(X)\'s presence is required at work'.

#pred wfh_mandatory(X) :: '@(X) must work from home'.

The second version has 8.

#pred holdsAt(wfh_required,T) :: 'you are required to work from home at time @(T)'.

#pred -holdsAt(wfh_required,T) :: 'you are not required to work from home at time @(T)'.

#pred fluent_changed(wfh_required,T) :: 'your work from home requirement changed at time @(T)'.

#pred initiates(wfh_order,wfh_required,T) :: 'a work from home order makes working from home mandatory'.

#pred terminates(presence_required,wfh_required,T) :: 'being advised that your presence is required terminates the requirement to work from home'.

#pred initiallyN(wfh_required) :: 'you were not required to work from home'.

#pred happens(wfh_order,T) :: 'a work from home order was issued at time @(T)'.

#pred happens(presence_required,T) :: 'you were advised your presence was required at work at time @(T)'.

And the second version doesn’t even deal with the issue of whether or not a person is a worker. That issue is presumed. And the second version can’t answer questions about more than one person at a time, though that should not cause the code to grow significantly.

That suggests that the amount of work involved in modelling legal rules in event calculus is much larger, and more difficult, than the amount of work involved in modelling it in a simpler paradigm that is not capable of doing abduction, or dealing with values that change over time.

So we face a cost/benefit risk. There is a risk that the cost of doing an encoding in L4, to give us access to these more impressive capabilities, is not worth it, because of how much harder it is than some of the alternatives. We need to think hard about whether using these kinds of features is something that we can make optional, for when it is necessary, and/or whether it is something that we can make easy.

Some Examples from Oracle Policy Automation

OPA is an example of one way of dealing with something akin to event calculus in a way that imposes a minimum of work on the user. In OPA, you generate a temporal variable from a list of events that have start and end dates, and a function that defines how to get the value from those events. Unlike a fluent, which is limited to yes or no, the variable can be of any type. You can have a boolean temporal variable, which is similar to a Fluent, but you can use strings, numbers, or anything else you want. The variable then behaves like any other in your rules. You can ask valueAt (similar to holdsAt for fluents) if you know the time you are asking about. But if you use that variable in a different rule just by naming it, the output of that rule is now also a temporal value (in fact, all variables were secretly temporal from the very beginning, just a temporal variable with only one value, for all times).

Let’s imagine we want to make a rule that say if one fluent is true at time T, then another fluent is also true at time T. In our implementation of BEC in s(CASP), we would say this:

holdsAt(fluent2,T) :- holdsAt(fluent1,T).

In OPA, you would say this:

fluent2 if fluent1

The fact that they are fluents has completely disappeared from the code, which is very friendly.

With regard to generating explanations, there is something to learn from OPA, too. You will notice that in s(CASP) I have at least 2 and sometimes more ways of saying the same thing. For example, wfh_required was also stated in explanations as “you are required to work from home.” But then there is the negation “you are not required to work from home.”

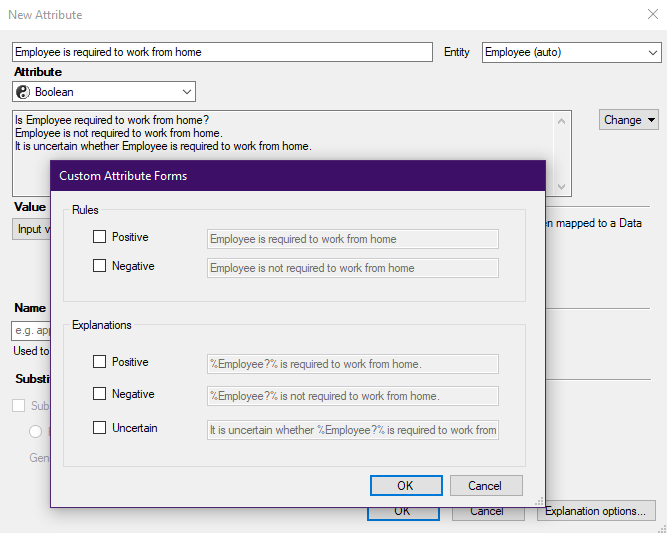

OPA does its best to shortcut this process by first saying that the root of your natural language explanation IS the symbol that you use in your rules. There is no short version like wfh_required. Everything in OPA is an object with a property, so if you have an object type called “Employee”, and you want to add “required to work from home” you would type “Employee is required to work from home” as the name of the property.

From that, OPA generates the version of the statement that you will use in rules, the version of the statement you will use in explanations, and the negation of both of those, plus a statement indicating the value is uncertain. If any of those five automatically-generated natural language statements are not to your liking, you can replace them.

So it generates the three different versions of the statement for you, making its best guess on the basis of the name for the attribute, which is a natural language statement.

This technique is not without its flaws. OPA, too, doesn’t require you to declare attributes before using them. So if you are trying to refer to the variable in your rules and you accidentally say “Employee was required to work from home” (note ‘was’ instead of ‘is’), OPA is going to create a brand new attribute for you, and you will be none the wiser until your code doesn’t work. That’s another reason we might want to have declarations.

But you can see that OPA is trying to eliminate as much of the busy-work as possible. That’s the right approach to take.

What’s Next?

This side-jaunt down into s(CASP)-land has been driven by a desire to avoid re-implementing event calculus on my own in Flora-2. I’m going to take a look and see how feasible it is to take BEC and re-implement it in Flora-2. If that works relatively well, I’ll probably take another shot at encoding the SAFE in Flora-2 but using basic event calculus, and see what sorts of things I’m able to do with it. If not, I may end up implementing SAFE in s(CASP) just to be able to look at the kinds of questions it can answer and the explanations it can generate for those answers.

Eventually, I would like to have one tool that did explanations, defeasibility, and event calculus all in the same place. L4 may end up being that tool.

Quick Notes

I will be talking about Blawx and Rules as Code at LSC ITC and CyberJustice Lab in January.

I will stop posting now for a couple of weeks. I need to spend more time shutting down my legal practice, and having an actual holiday break. The next time you hear from me I should be in Singapore, spending two weeks isolated in a hotel room.

Happy holidays, and I’ll see you in 2021.