Another Rules as Code example from ICAIL 2019

A short while ago I wrote a post about how you can use AustLII’s DataLex to take legislation and turn it into code.

This week I’m attending the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law (ICAIL 2019) at the University of Montreal Cyberjustice Lab. As I type, I’m in a tutorial session discussing a new open-source tool for Rules as Code, called NAI.

Encoding The Law

I decided to re-implement the same code from the previous post in order to see the differences. As you might recall, it was section 2 of Alberta’s Mental Health Act, and reads as follows:

Admission certificate

2 When a physician examines a person and is of the opinion that the person is

(a) suffering from mental disorder,

(b) likely to cause harm to the person or others or to suffer substantial mental or physical deterioration or serious physical impairment, and

(c) unsuitable for admission to a facility other than as a formal patient,

the physician may, not later than 24 hours after the examination, issue an admission certificate in the prescribed form with respect to the person.

In NAI, you set out the law and the questions you want to ask in different contexts. To set out the law, you create what NAI calls a “legislation” file.

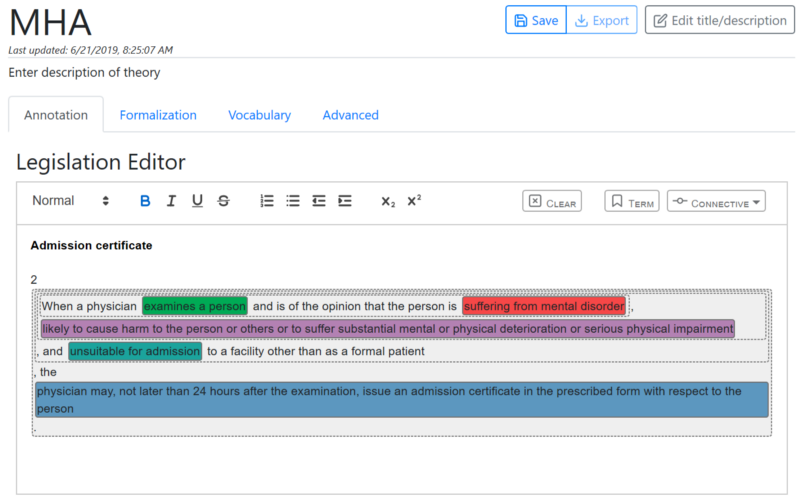

You start with the text of the legislation, and then you highlight sections of the legislation and annotate them as either “terms” or “connectives”. So in the picture below, the paragraph as a whole you can see has been highlighted in a grey box, which creates a “if permission” connective. The smaller grey boxes are all “and” connectives, and the coloured boxes are terms.

I found it easier to get the demo (which is still in beta) to work by getting rid of all the line breaks in the legislation and taking out section numbers, but I’m not sure either was necessary.

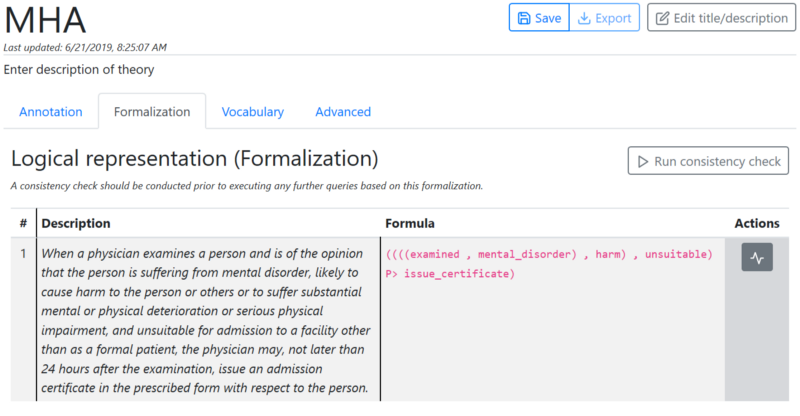

When you are annotating “terms” (the coloured boxes), it allows you to re-use the terms you have already defined, or create new ones. From these annotations it builds a formalization, which you can review.

Encoding a Query

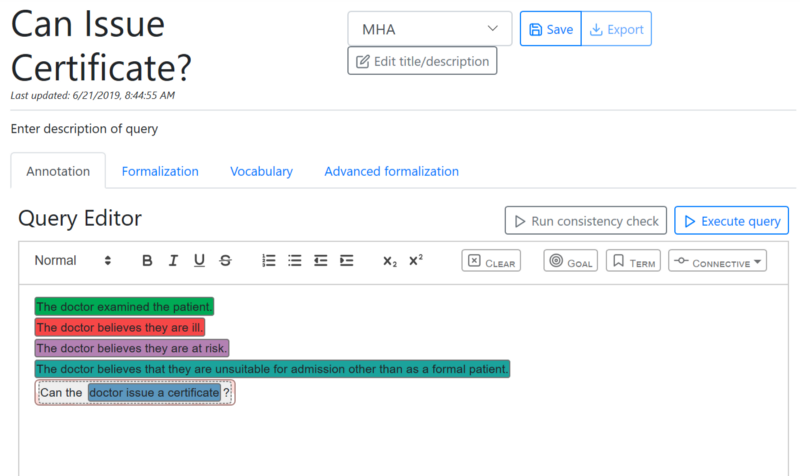

Then, to use the code you create a “query” that includes the things you know to be true and the question you want an answer to. It proceeds in the same way, where you start with plain text, and then annotate it to create the query.

This feels slightly artificial, because the text does not exist anywhere before you start typing it. So typing it and then annotating it feels like two steps where one might have sufficed. But the parallel to the way legislation is annotated, and the fact that you can re-use the terms used in the legislation, might make the learning curve less steep.

When you start the query you tell it what legislation you are using, and then you have access to all the same terms that were created in the legislation file.

So what I want to do is set out that all the required factors have been met, and then ask whether or not the doctor is permitted to issue a certificate.

At first, I was getting errors, because I was incorrectly asking whether or not the doctor HAD issued a certificate, when what I wanted to ask was whether or not the doctor was permitted to do so. NAI uses a deontic logical language, which means that obligations, permissions, and prohibitions are some of the connectives that you are able to use, in order to be able to ask questions like “in this circumstance what is permitted?”

Here is what it looks like when the query is typed in, and annotated.

You can see there are three boxes surrounding the last line. The blue box refers to the “issue certificate” term that was created in the legislation. The next, grey box, is a “permission” connective. And the slightly reddish one surrounding the grey one is the “Goal” connective, which tells the tool what you are trying to find out.

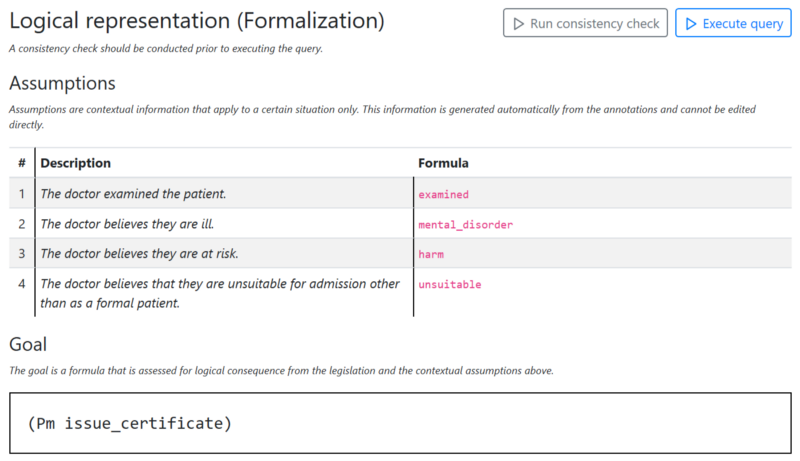

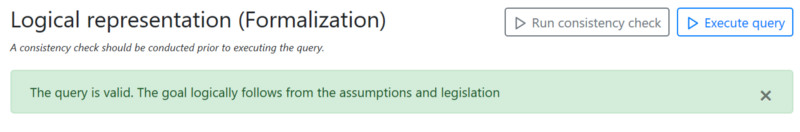

The formalized version of the query looks like this:

Now, you can just run the query by clicking on the “execute query” button you can see above. The result looks like this:

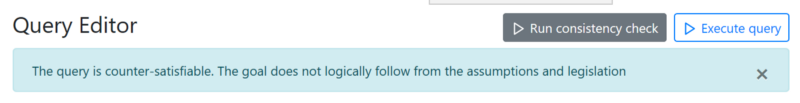

If I delete the line saying that the doctor has examined the patient, save the query, and run it again, I get this:

Impressions

Compared to the DataLex tool, NAI has some advantages. First, it is capable of dealing with more complicated predicate logic, allowing you to ask much more complicated questions, like “are there any doctors who are permitted to issue a certificate?” (I didn’t use those features in the example above to maintain symmetry with the DataLex example.)

If the ability to ask questions about permissions, prohibitions, and obligations is valuable to you, it also integrates those features.

It also helpfully distinguishes between the law, and the question you are currently interested in asking.

There are also disadvantages. Unlike DataLex, NAI cannot ask you for the pieces of information it needs in order to answer the query. If you remove all the facts, and run the query again, you just get NAI telling you that the goal query is not provable.

Is “Highlighting” the right interface for logic programming?

What is really interesting to me about NAI is the highlighting and annotating metaphor for generating formalisms. DataLex, by comparison, uses something called controlled natural language to give people a more user-friendly interface to logic programming.

I think that is the real obstacle to seeing these tools finally adopted, and I’m very pleased to see someone who is trying something innovative on the user interface side.

I’m not convinced, yet, that highlighting is the right approach, for a couple of reasons. Or at least not on its own. One reason is that legislation can be written in ways where the logical elements are disconnected from one another, which would require re-writing the legislation before annotating it. There are also a lot of assumptions that are not stated explicitly in a law,

Open Source

The other big advantage of NAI over DataLex is that the tool is 100% open source. It is available on GitHub.

So whatever features it does not have can be added by whoever needs them, and there is no cost for a lawyer or legal aid organization to use it to automate legal services for people who are unserved by the existing legal services market.

Even if you run it on the developer’s servers, it is a more fully-festured app than DataLex, allowing you to save and share what you have built. Check it out here.