Notes from Prolala 2022

I had the opportunity to participate in Programming Languages and the Law (ProLaLa 2022), a workshop held as part of the Principles of Programming Languages 2022 conference (POPL 2022).

All of the day’s events are available to watch on YouTube.

It’s sort of hard to imagine an academic conference with a topic closer to my interests, and it did not disappoint. Here’s an extremely succinct version of what went down.

Keynote - James Grimmelman on a Research Agenda for Programming Languages and the Law

Professor Grimmelman’s objective was to set out the sort of academic questions that remain unanswered in the space, and his suggestion touched on a number of the topics being discussed, as well as user interface design for the development environments for programming languages for legislative drafting, and the like.

“As a person who has worked with both programs and law, it is a much more painful experience to work in the legal space.”

Amen, brother.

“Formalizing a body of law forces you to understand it in a much deeper way.”

This is something that speaks to my experience as a lawyer who writes code. I have never encoded any legal rules and not known more about the rules for merely having attempted it. It always teaches you something.

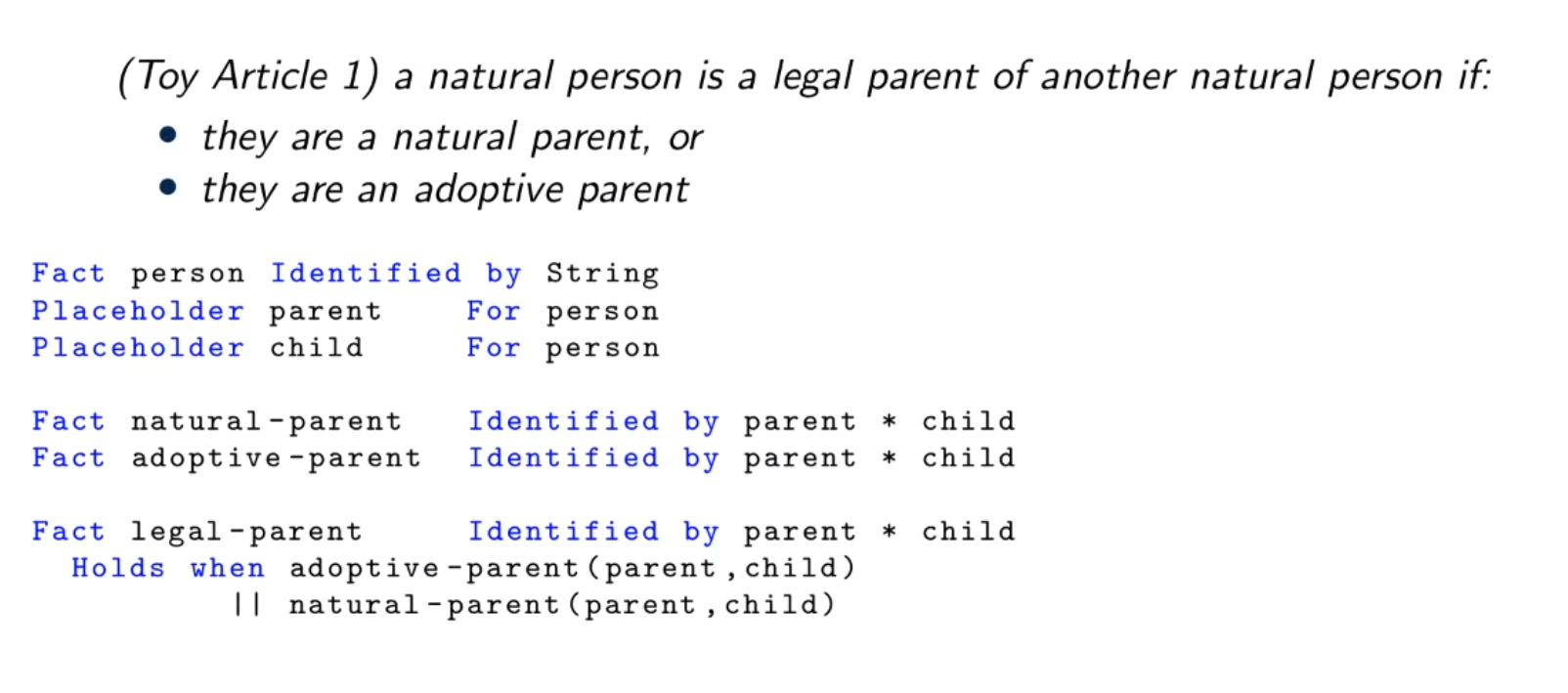

Shrutarshi Basu - Legal Calculii

Shrutarshi Basu spoke about the relationship bewteen calculii and programming languages, and how “legal calculii” get implemented in programming languages for law, using the examples of Orlando and Catala.

A calculus is just a way of making statements, and deriving new statements from

the statements you already have. For example, in math, you have a rule that

allows you to convert the statement x(a+b) into the statement xa+xb.

In law, you can convert the statements Jason owned the car. Jason sold the car to Jane.

into the statement Jane owns the car. That can be represented as a calculus,

and automated in a programming language for representing the sale of goods.

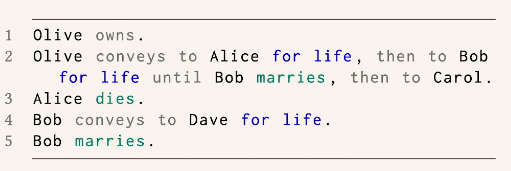

Orlando

Orlando was completely new to me. It seems like a controlled natural language DSL specifically for manipulating the possible future states of the gifts in a will. Because it is targeted at a specific legal task, and may not be generally applicable for all kinds of legal concepts. That makes it a good example for a talk about legal calculii, though.

It doesn’t seem to be available online, but it is implemented in Littleton, which is discussed below.

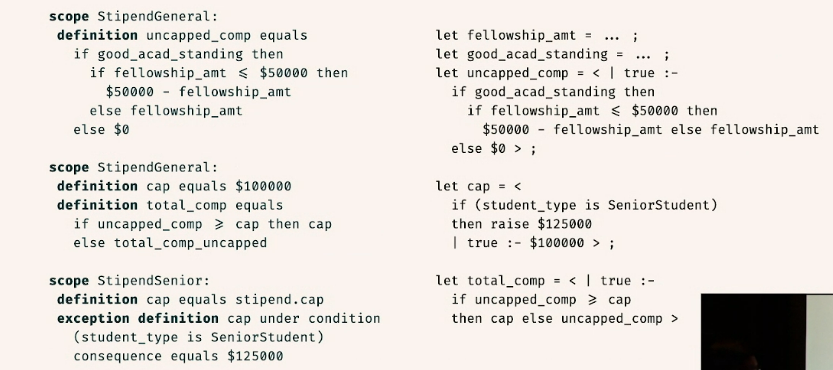

Catala

Catala I am familiar with. It is a functional programming language with defaults for expressing the content of quantitative legislative provisions, such as tax and benefit systems. Catala implements a version of lambda calculus with the addition of defaults.

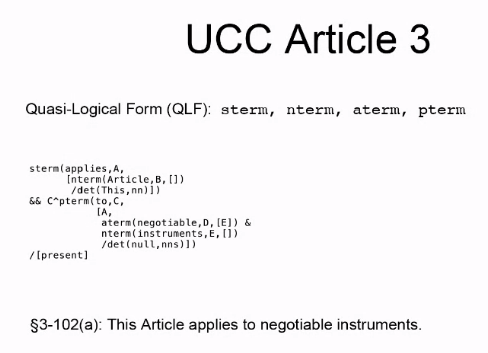

L. Thorne McCarty on All You Need is LLD

L Thorne McCarty talked about his Language for Legal Discourse (LLD), an intuitionistic logic programming language for law.

Thorne has posted his slides and his notes online, and will be hosing a Q&A on Friday the 28th, as part of the Virtual Workshop of POPL.

His talk was a recap of his previous work on LLD going back to the 1990s. Unfortunately, it was extremely technical, and content rich, and the time available did not make it possible to get a clear understanding. The examples of code that he provided, which he indicated had not been shared elsewhere, were also very large, and difficult to read.

It is difficult to know whether LLD truly is “all you need”, because as McCarty notes it has never been fully implemented. McCarty suggested that now might be the time to remedy that. That may be so, but I for one do not understand the benefits of LLD sufficiently well to recommend that project.

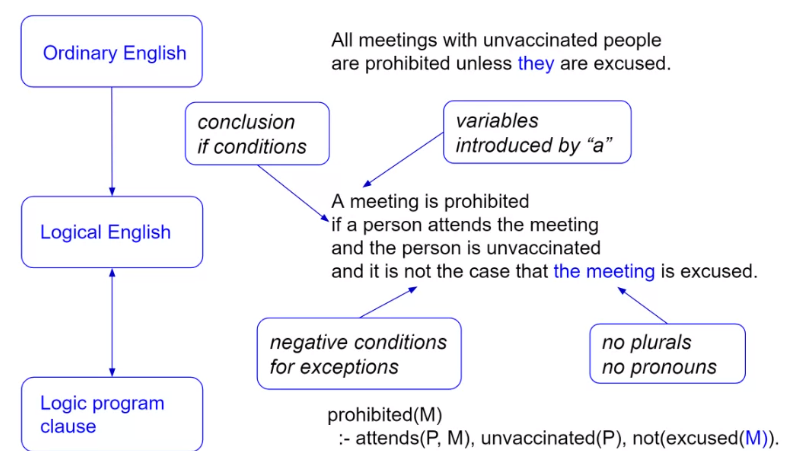

Logical English as a Programming Language for Law by Robert Kowalski

Continuing the presentations from illustrious members of the field like McCarty, we had Robert Kowalski do a very accessible explanation and demonstration of Logical English.

I have to say that I have seen Kowalski speak on Logical English before, and he is getting better at it. This was a straightforward explanation of how a rule is turned into Logical English code, and what you can do with that code once it is written, including a demonstration inside the SWISH interface for SWI-Prolog.

Logical English is an untyped controlled natural language that compiles down into Prolog and (I think) can take advantage of the event calculus features of LPS.

Logical English is available as an online system at logicalenglish.logicalcontracts.com/example/LogicalEnglish.swinb, where there are some simple demos you can try.

Kowalski notes, correctly in my view, that while Logical English is easy to read, that does not make it easy to write. It is still a programming language, and requires knowledge of the syntax to use properly.

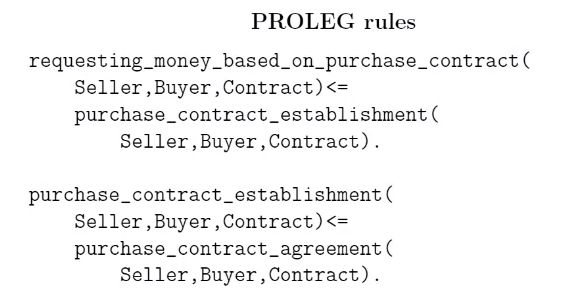

PROLEG by Ken Satoh

Third in the series of the luminaries of the field was Ken Satoh, introducing his tool PROLEG. PROLEG is essentially a different way of writing Prolog, aimed at people encoding the justification process of courts, after facts are no longer in dispute and the judgement has been made. It differs from Prolog in that instead of using negation as failure, it uses defaults and exceptions. This matches well with the civil law system in Japan, which provides default presumptions with regard to all of its legal concepts.

Satoh has found defaults and exceptions were easier for lawyers to reason about than negation as failure.

I find that surprising, and I wonder if it is true in a wider context. Negation as failure, to me, has always seemed very intuitive, because it has a legal correlation in the concept of the distinction between “not guilty” and “innocent.” As lawyers, we are familiar with the distinction. “Not guilty” means there was no evidence sufficient to prove guilt. “Innocence” means there was evidence to eliminate the possibility of guilt, proving the opposite of guilt. Negation as failure applied to guilt is “not guilty”, and logical negation applied to guilt is “innocent.”

That said, legislation is drafted with defaults and exceptions, so I have no difficulty in recommending that any Rules as Code tool should have that capability, too.

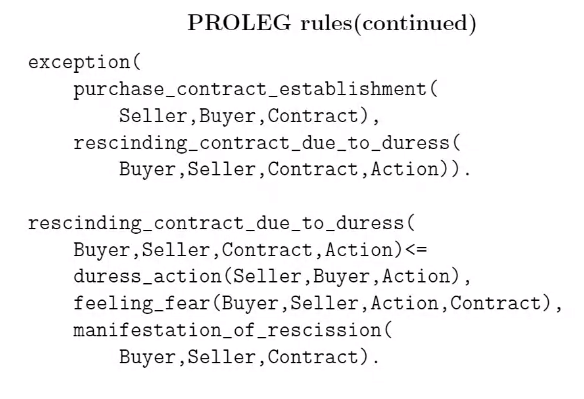

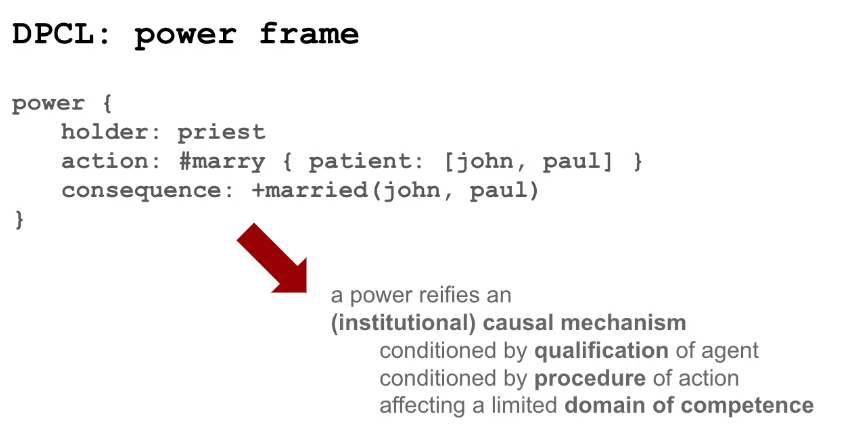

Giovanni Sileno - DPCL

Giovanni Sileno then spoke about DPCL, which if I understand correctly is a semantics-free representation language for norms. It seems to be based on Hohfeld’s terminology of rights and powers, etc., and allows norms to be documented in JSON. While it doesn’t have a complete semantics it does have some rewriting rules that can be applied to it, and the developers are working on the possibility of an operational semantics for it.

Generally, I’m skeptical of the usefulness of languages for representation that don’t have a semantic component. I’m also not sure that the kinds of problems that we have, right now, in the Programming Languages and Law space have to do with things like the power to impose obligations. The low-hanging fruit, as it were, seems to be a degree of magnitude less complex than that.

It was suggested that DPCL could be used as a means of recording norms, and allow a modeller to decide on a case by case basis how to implement those norms operationally. I find it a little difficult to imagine that a modeller would volunteer to add a layer of translation to their work without some major benefit for doing so, and I’m not sure yet what that benefit would be.

It strikes me as something like LegalRuleML, that will become more useful the more tools are integrated with it, but the first few tools to integrate it would need to do so more or less on faith.

L Thomas van Binsbergen - eFLINT

eFLINT is an executable language with state, transisions, violations, deontic and hohfeldian concepts applied to both states and transitions. It implements something approximating defaults and exceptions by allowing new rules to “extend” the meaning of rules already stated. It features a web interface for version 1 of the language, a REPL, the ability to write eFLINT code inside a Jupyter notebook, and it has Haskell, Java, and Scala implementations.

It is often used to write “agents,” more than one of which can be activated at the same time to see how they interact with one another in a given context.

It seems like a serious general purpose legal tool that has been under development for a while, with a focus on ease of use. I will need to give it a try.

Short Talks

We then went into the “short talks” section of the day.

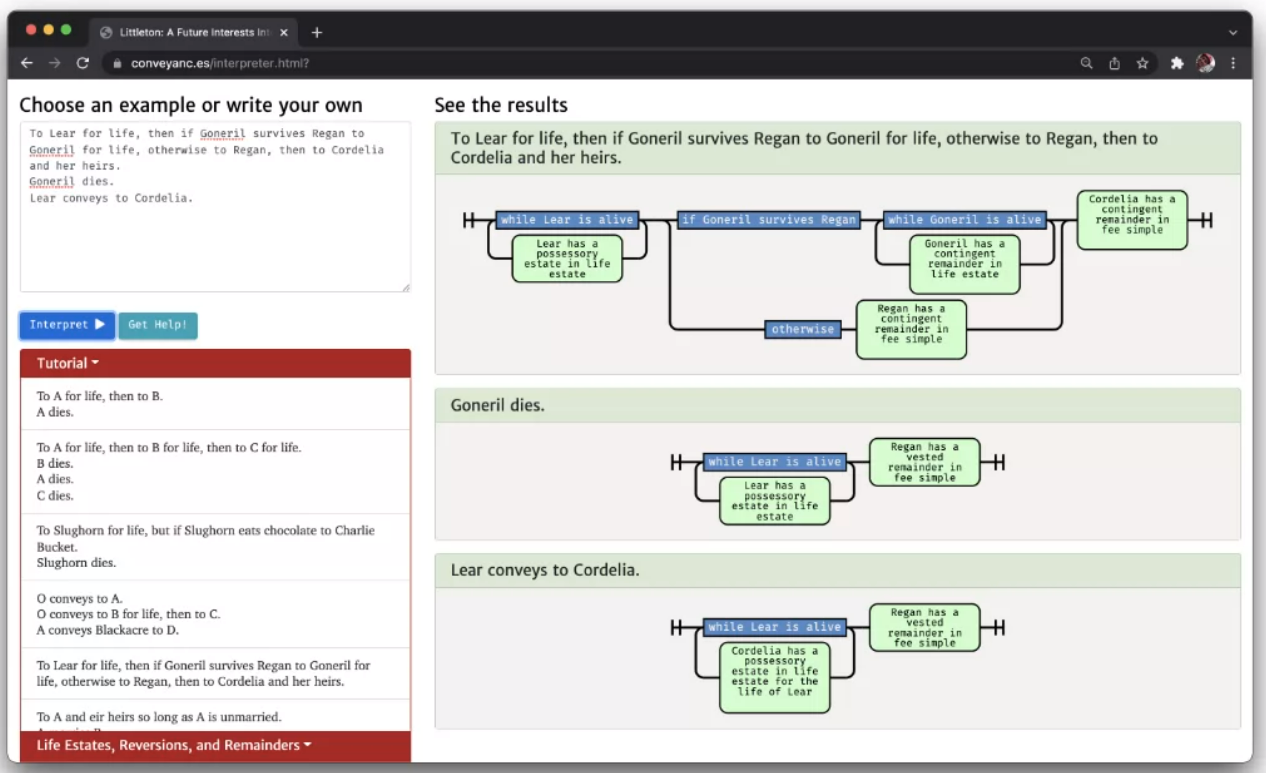

Anshuman Mohan - Littleton

Mr. Mohan introduced Littleton, which essntially takes the Orlando programming language for gifts in wills, and converts statements in that language into whare are called “railroad” diagrams.

Railroad diagrams are more typically used to represent syntactic structures, where the loops are used to indicate that an element can be repeated. It seems to me like in Littleton the loops are being used to represent the idea that a thing may continue to be true over time, and I think that makes the railroad diagrams a little less intuitive in this context than they might otherwise be.

The diagrams also don’t simplify the process of generating code, they only visualize the code that has already been written. It seems like a valuable tool for teaching some of the intricacies of property law, but like Orlando, it doesn’t seem to have wider applicability.

You can try Littleton yoruself at https://conveyanc.es/.

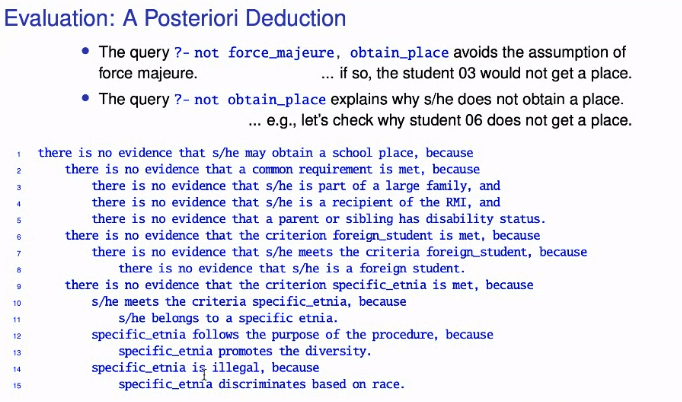

Joaquín Arias - Representing Administrative Discretion in Goal Directed Answer Set Programming

Professor Arias did a demonstration of the use of s(CASP) to represent administrative decision-making.

As readers of my blog will know, I’ve spent a lot of time over the last year working with s(CASP), and it is currently my favourite general-purpose tool for Rules as Code because of its support for explanations, models, constraints, and abductive reasoning, all in open source.

s(CASP) deserves a lot more than 10 minutes of your time, if you are interested in tools that are useful in this space. Introductory materials are pretty seriously lacking, at the moment, though.

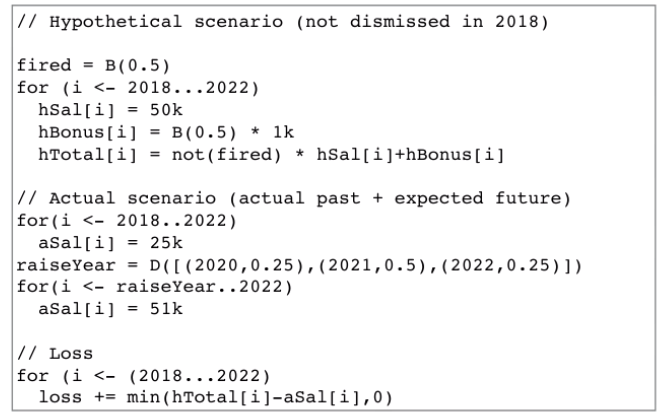

James Cheney - Probabilistic Programming for Employment Claims

James talked about probabilistic programming languages, which allow you to express things that may or may not be true, and the certainty you have about them, and combine them in ways that preserve the probabilities in a statistically accurate way. It was a helpful demonstration for people not familiar with the concept of probabilistic programming, in which it was used to calculate the salary that a person might have lost due to being unlawfully dismissed, based on some uncertainties about how long they might have been unemployed, and the type of employment they might have found.

Probabilistic programming may also have applications in evidence (prior likelihoods), and in loss of chance litigation.

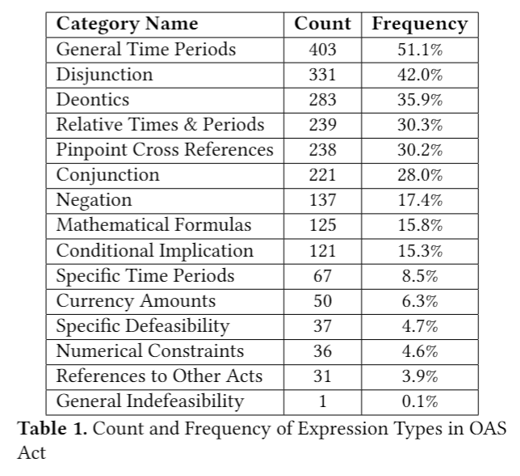

Jason Morris - Prevalence of Expression Types in Legislative Text

Who let this guy in here?

I spoke very briefly about some work that I did at Service Canada attempting to discover how frequently certain expression types appear in the Old Age Security Act. The short version is that dates and cross-references show up a lot more frequently than I would have thought, which suggests that languages that have features for implementing dates and cross-references might make my life easier when encoding that Act.

Cross-references, in particular, would in turn require the language to have a structural isomorphism between sections of law and sections of code, so that you can refer to “this Part” or “section 4”, and your code will know what code that relates to. That, in turn, requires that the language have features that allows you to maintain that structural isomorphism, without reformulating. That suggests that defaults and exceptions is an important feature, even if they don’t show up as often in legal texts, because combining a default and an exception into a single rule makes it difficult to know which section of code represents what rule.

Law Smells - Corinna Coupette

Corinna Coupette’s talked about some work her team had done in making a list of “law smells”.

“Code Smells” are a surface indication in software that usually corresponds to a deeper problem in the design of a code system. For example, a programmer might see that you have an unsually large number of comments explaining the meaning of your code, which might be a surface indication of a deeper problem that you have not chosen a good abstraction or used a good naming system for the components of your code.

A “law smell,” then, is a surface problem with how a law is written that suggests a deeper problem in the way that law has been structured or designed.

To be honest, some of the things that she went on to describe as law smells were not so much surface indications of something wrong underneath, but problems visible in the text of the law. Ambiguous logic, for example, is a problem in and of itself. So I don’t know how well the analogy works, here.

Other smells seemed to be describing features of laws that were either not strongly indicative of problems (e.g. long sections), or are actually considered good drafting practice.

I did hear Ms. Coupette say that the smells were based on things that the members of the study found frustrating in reading laws. But stop lights can be frustrating. It doesn’t make them a bad idea. I’m not sure if these “law smells” are truly analogous to “code smells”. Or if it really matters. Will need to read the paper more closely to have a better idea.

Jeffrey Bilik, Nel Escher - Cod(e)ifying the Law

This was perhaps the single most enlightening part of the day. That rarest of things, high quality qualitative user research into the design of tools for the automation of law.

Having seen evidence that systems for automating legal advice have mistakes in them, they wanted to know how these errors were generated, and what it might be possible to do with tools and techniques to mitigate them.

The researchers created a legal automation task in JavaScript and HTML, and gave it to three different categories of “teams”:

- One computer science graduate student

- Two computer science graduate students

- One computer science graduate student and one law student

The task was designed so that it could be implemented in more than one way, and intentionally referred to a vague section of law, “undue hardship.”

They then recorded video and text chat content while having these teams complete the legal automation task, and carefully analysed the data to make a number of really noteworthy discoveries. They interviewed the participants to ask how confident they were in the accuracy of their tool, and whether they would be comfortable with sharing it with the public, and further, whether they would be comfortable with using it as a replacement for a judge in deciding real cases.

The results are, if I can be frank, sort of horrifying.

- The vast majority of the resulting tools had legal errors

- Even teams that had specifically discussed a problem and how to avoid it ended up failing to avoid those problems

- Most law students suggested test cases for the tools, but never suggested enough to cover the scope of possible problems.

- Using interdisciplinary teams increased the quality of approaches to vague terminology

- The participants judged their tools as being far better in legal quality than they actually were

- Law students were unanimously opposed to automating decision making using their own tools.

- Computer scientists were 75% in favour of automating decision making on the basis of their own tools.

There is so much to be said, here, we’re going to have to leave it for another blog post, too.

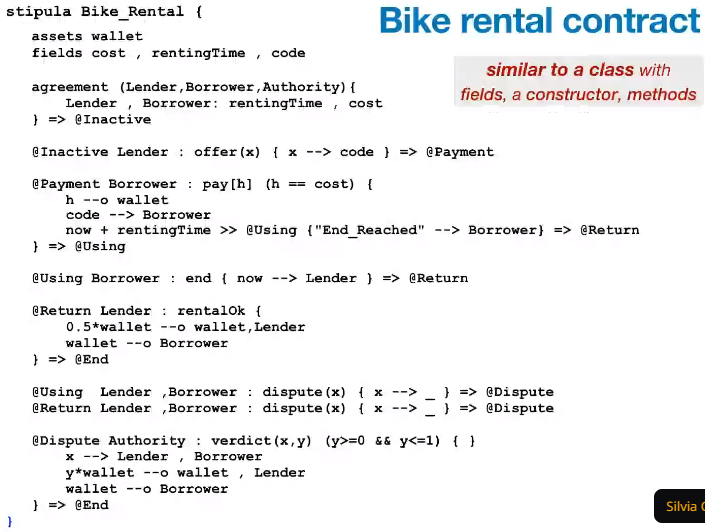

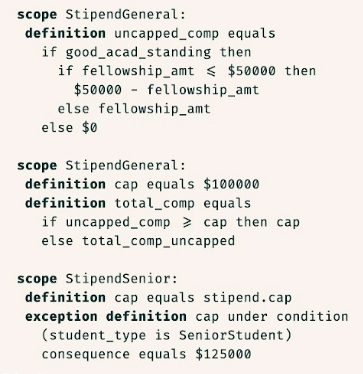

Silvia Crafa - Stipula

Stipula is a language that was created for implementing contracts in code, with an interesting approach to maintaining human influence on the execution of the contract in appropraite ways. Ms. Crafa refered to the idea of complete automation of contracts, the standard mantra for smart contracts, as “defective.”

The tool is also designed to allow reasoning about behavioural equivalence between contracts, to do type inference, to do liquidity analysis to see if adhereing to a contract with drain anyone’s financial resources, etc. It also has an interesting mechanism for dealing with the difference between assets (pools of resources that can be assigned exclusively to different contracts, like cash), and standard values, allowing you to see the effects over time on your asset availability.

It also has an interesting mechanism of implementing a state-machine sort of desctiption by prepending section sof code with the state in which they are available, and appending the states that are generated by the execution of that portion of the code.

I have some ideas about visal methods of diagramming these sorts of things, but this is one of the more intuitive approaches I have seen for doing the same thing in text.

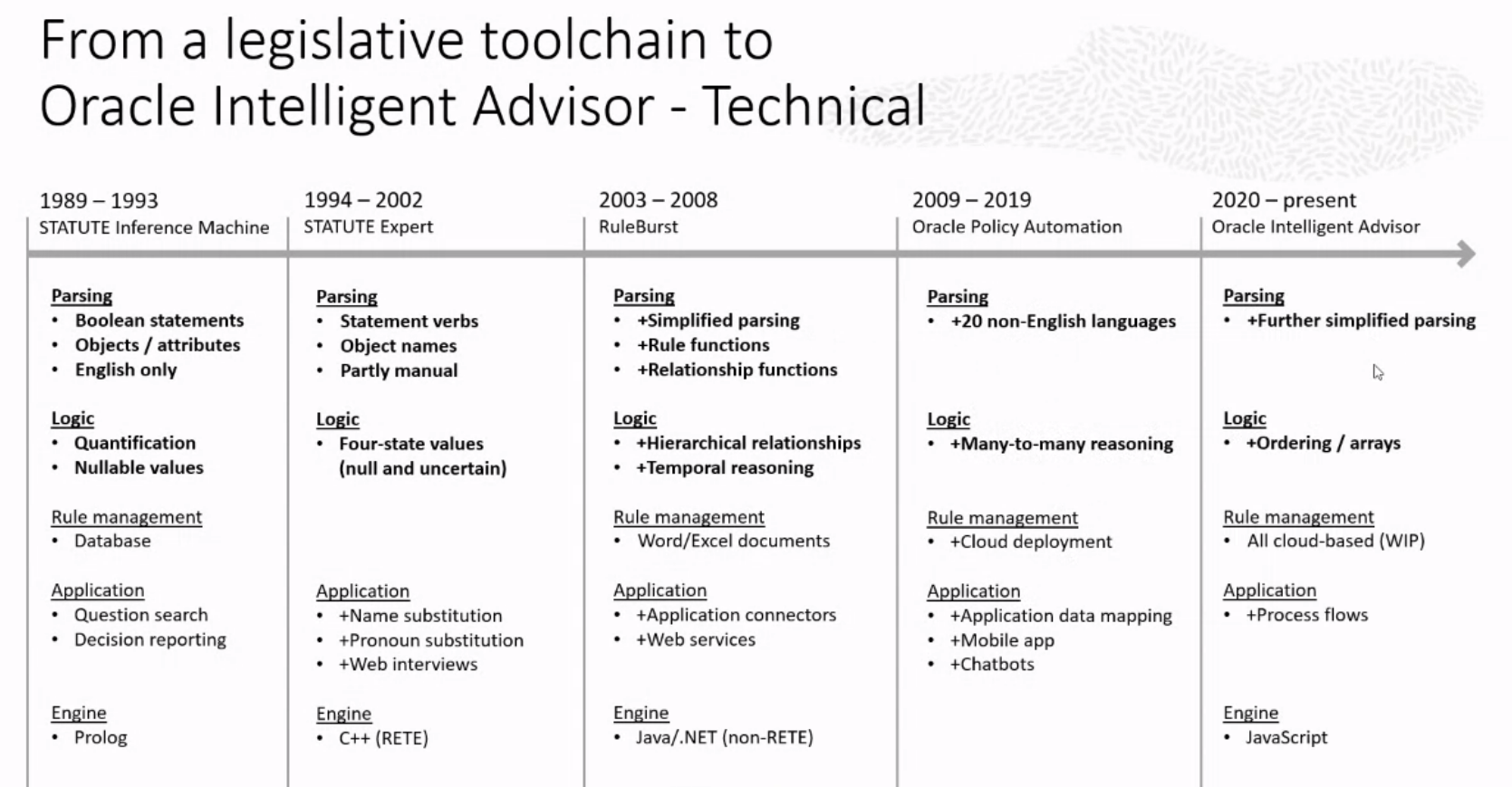

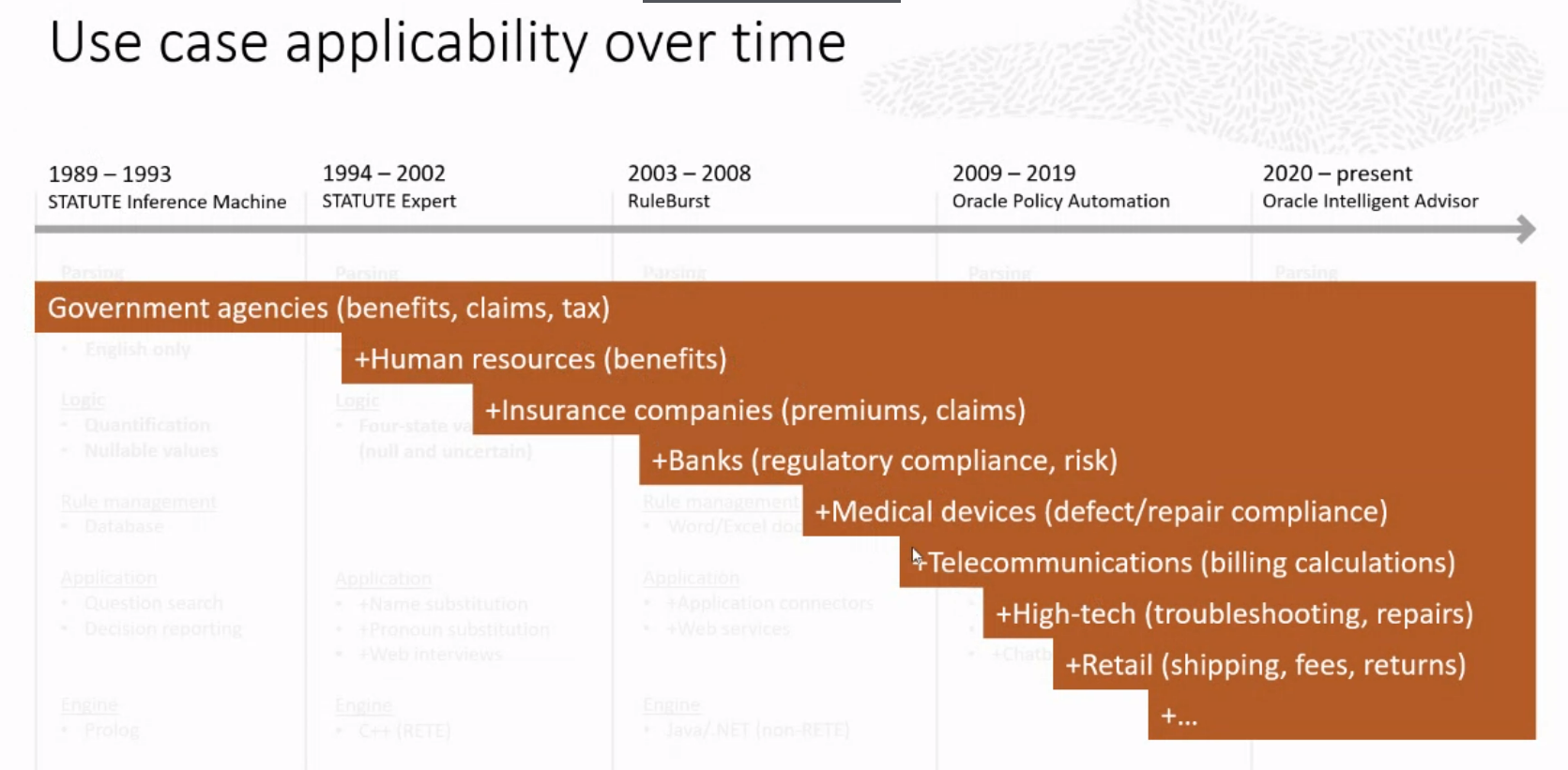

What Does a Toolchain for Automating Legislation Eventually Become (or: The History of Oracle Intelligent Advisor)

Don Syme is a guy who designs F# for Microsoft. But back when he was 19 years old, he was a C and Prolog developer, and the third employee at SoftRule, a company that created a tool called STATUTE in 1989.

Don Syme and Surend Dayal gave a history of the STATUTE tool, and how it evolved into its current form, Oracle Intelligent Advisor. David Fifield of Oracle then gave a demonstration of the current state of the tool. The session was advertised as “what to expect if you succeed” in the world of tools for encoding legislation.

The short answer? Expect that it will be used almost exclusively for corporate policy.

STATUTE was originally created in 1989 by Peter Johnson, a national expert on Australian administrative law, and David Mead, a programmer. It was a tool aimed at taking the programmers out of the task of updaing your encoded representation of relevant rules by providing a controlled natural language interface in which to write the code.

Phases:

- 1989-93 STATUTE Inference Machine; Rulesbase Workshop

- 1994 - 2002 STATUTE Expert

- 2003-2008 RuleBurst; New non-RETE algorithm

- 2009-2019: Oracle Policy Automation

- 2020 - Present: Oracle Intelligent Advisor

David Fifield talked a little about the reasoning features, and did a live encoding of an example statute and built an app in Oracle Policy Modelling.

If you aren’t familiar with Oracle Policy Modelling, and you are interested in how Rules as Code can be made easier for non-programmers, you owe it to yourself to give it a try. In terms of user friendly interface, and the ability to generate enormous value from nothing more than the rules, it is absolutely in a class of its own.

I was surprised to learn that it is actually taught at a law school in University. I thought Neota Logic and Docassemble had that market cornered..

OIA is also a complete non-starter as a solution for Rules as Code in the public or non-profit sphere, because it is closed source and extremely expensive. The question was raised at the conference of whether Oracle has considered realeasing a reference implementation of their reasoner to address black-box concerns arising from legislation like GDPR. The answer was that they had, but that they had not yet figured out how to make it acutally happen.

With any luck OPM will eventually follow in the steps of Microsoft’s Z3, and be made open source as soon as there are steps toward a viable open source competitor.

In addition to being problematic because it is closed source, OPM’s approach to encoding is to force the user to write one rule that answers each question. That means you cannot maintain structural isomorphism with your source legislation if the source legislation uses exceptions to defaults.

This walk down memory lane was fun, enlightening, and fascinating.

Also frustrating, because the best thing that exists for rules as code, technologically, is behind a proprietary fortress wall. If you’re interested in helping me solve that problem let me know.

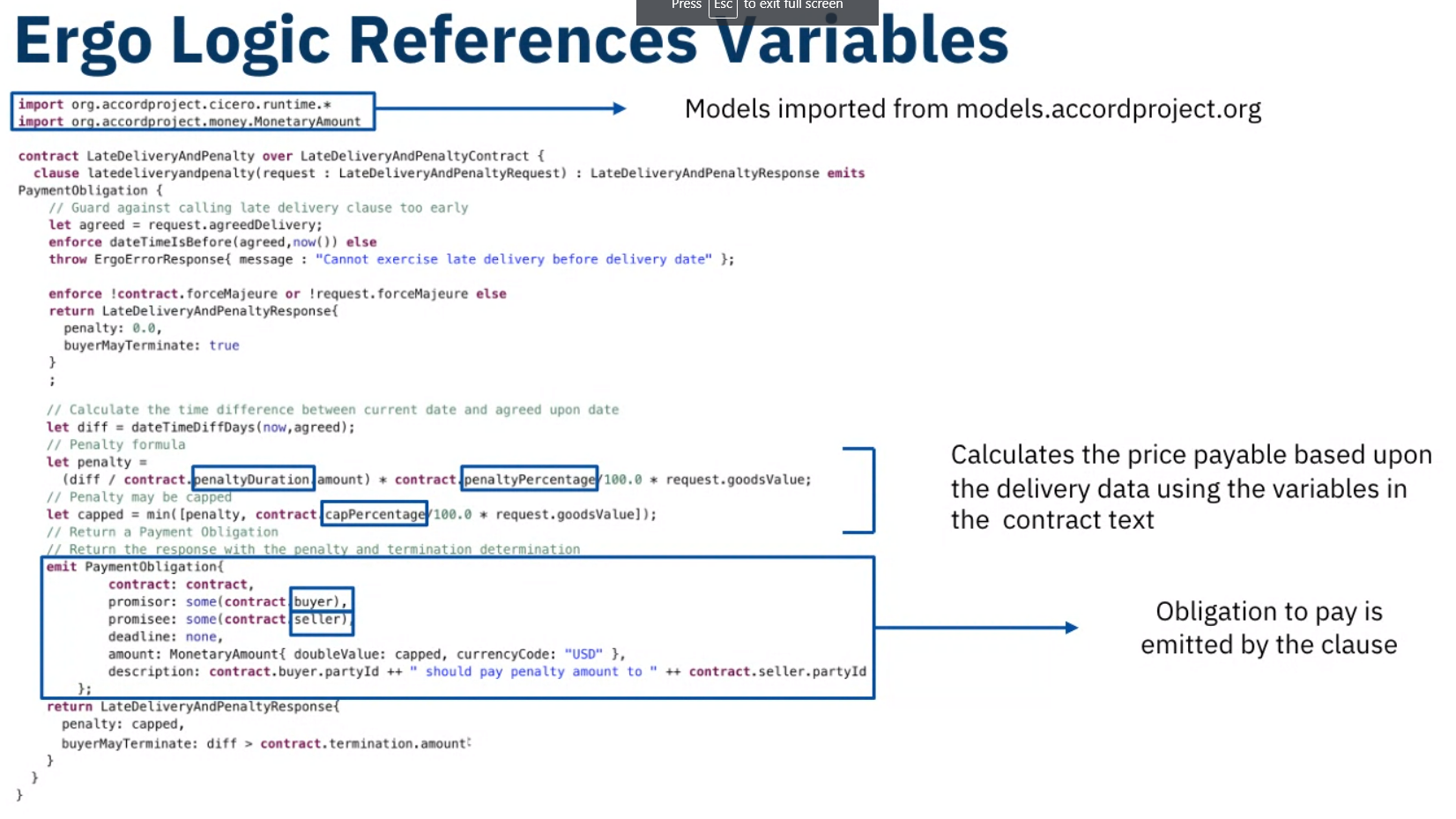

Nial Roche - Ergo

Next up was Nial Roche from the Accord Project who talked about Ergo, the executable component of their tech stack for smart contracts. Ergo is the executable programming language, Concerto is their data structure specification language, and Cicero is their document automation tool.

Ergo is a functional language, and its compiler is implemented partially in Coq in order to provide a stepping stone to being able to verify smart contracts specified in Ergo itself. It is targetted at agreements specifically.

Chris Bailey - General Library of Reusable Legal Components

I did not understand this presentation the first time I watched it, so I watched it again today, and holy crap, what Chris Bailey has accomplished here is impressive.

The short version is that Chris is a law student who wrote an encoding of the rules for calculating certain tax provisions. He then wrote another piece of code that can be used to formally verify that the first piece of code is consistent with the law, on a section-by-section basis.

He then did the same thing with a relevant tax form, to see if the tax form was generating answers that were identical to the law, and he discovered that it was not.

That’s the short version. The long version is going to go into its own blog post, because wow.

Wong Meng Weng - L4

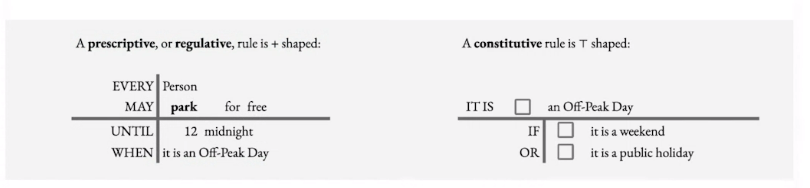

Meng is my former boss at Singapore Management University Centre for Computational Law, where they are working on a new language for contracts and laws called L4. He provided a pre-recorded video of his talk (given the time difference to Singapore), which showed off their latest iterations.

They are currently working with a “spreadsheets for law” approach by using an actual spreadsheet as their IDE. L4 code is currently expressed in a unique 2-dimensional expression language inside Google Sheet spreadsheets. Full marks for interface innovation!

His presentation talked about how that code can then be translated into various other tools such as Uppal, Answer Set Programming, Prolog, CTL, and others in order to accomplish various tasks. The CTL work, in particular, falls into the same formal verification spaces as Lean above, and Catala below.

It wasn’t clear from the presentation how much of that translation can currently be done automatically, as there wasn’t a demo involved. Once it is possible to play with to generate web apps and the like, it will be fascinating to see if the nested “plus-shaped” and “tee-shaped” interface will be intuitive for legal users.

Denis Merigoux - Catala as a Proof Platform for Law

Denis Merigoux presented on his work on extending Catala, a functional programming language that he helped design for encoding tax and benefit statutes, to make it a platform for doing formal proofs of properties of legislation.

This is very similar to the CTL work done with L4, and the work done in LEAN, except that where LEAN starts with formal verification, Catala starts with being able to reliably do real-world calculations, and Denis is now looking to add formal verification to the toolset.

My Closing Thoughts

On Formal Verification

The last three presentations all had to do with approaches to formal verification of legislation, though L4 and Catala are also very much primarily concerned with execution.

I have been a skeptic as to the value of formal verification, for a couple of reasons. First, I have generally seen it implemented as something that needs to be done in addition to your actual automation, sometimes completely disconnected from it, requiring you to model your original code. Formal verification is useful if you need to go from the level of confidence you can have with testing to the level of confidence that you can have with mathematical proofs. I can see a few limited circumstances in which that is justified merely by virtue of it being possible, such as systems that calculate taxes and benefits for entire countries. Outside of that, it seems like a level of confidence that probably wasn’t worth the cost.

The second reason is that most formal verification approaches that I have seen assume that if you say something incoherent in your code, your software should “error out.” That suggests to me that they can only be used in places where the laws are well-written, and I don’t feel like I can guarantee that about any particular law, or that it is a good idea to represent only the well-written parts.

I’m still skeptical, but I have to say that after this conference, my attitude has softened. Particularly Chris Bailey’s presentation was persuasive that this might not be such a costly approach with the right tools, which makes it valuable in a wider array of applications.

On AirMeet

AirMeet was the platform on which the ProLaLa conference was hosted. It’s my first time attending a hybrid in-person and online academic conference, after attending a number of virtual conferences. There were about 40 attendees throughout the day. It’s by far the best virtual conference experience I’ve never had. Highly recommended as a technology platform.

On ProLaLa 2022

The workshop itself was an unmitigated success. The presentations were fascinating, extremely valuable to me (with the one exception that I don’t learn anything while I’m the person talking), and I was delighted by the topics covered and their importance to my work.

Highlights are the retrospective on OIA, the research into the reliability of automated legal solutions, and the presentation on eFLINT, which was entirely new to me, and which has joined Catala and Ergo as tools I would like to learn to use.

Enormous congratulations to the organizing committee, the chairs, the student volunteers, the presenters, and the attendees. Well worth the fee for attending POPL 2022, and I will certainly be back.