GPT4 and Rules as Code

With the release of GPT4, and in particular with the demo video showing ChatGPT4 being used to answer a question about tax laws, people have been asking my thoughts about whether Rules as Code is still necessary. Should we be getting human beings to deal with encodings of legislaton, or should we just let large language models do the legal reasoning? Are there parts of the Rules as Code process that should be dealt with by things like GPT4? How does Blawx fit into this brave new future?

Can GPT4 Do it Alone?

The first question is whether GPT4, or its Chatbot cousin ChatGPT4, are “all you need” for legal reasoning. Here, I have two main concerns. First, I’m not sure that it has all the reasoning capabilities that we can get from symbolic methods. Second, even if it did, I don’t know that we can trust it.

ChatGPT4 is Still Not Great at Reading Laws

I put the text of sections 3 and 4 of the Old Age Security Act into ChatGPT4, and asked it whether a person born in 1950 with a valid immigration visa qualified for a full monthly pension.

Here’s the answer I got, leaving out the (very important) part about not relying on ChatGPT4 for legal advice.

Based on the text of Section 3 and 4 provided, a person born in 1950 with a valid immigration visa might be eligible for a full monthly pension under Section 3(1)(b) if they meet the following criteria:

On July 1, 1977, they were not a pensioner but had attained 25 years of age and resided in Canada or, if they did not reside in Canada, had resided in Canada for any period after attaining 18 years of age.

They have attained 65 years of age.

They have resided in Canada for the 10 years immediately preceding the day on which their application is approved or, if they have not so resided, they have been present in Canada prior to those 10 years for an aggregate period at least equal to three times the aggregate periods of absence from Canada during those 10 years, and have resided in Canada for at least one year immediately preceding the day on which their application is approved.

Additionally, according to Section 4(1), they must be legally resident in Canada on the day preceding the day their application is approved. The person’s valid immigration visa could potentially indicate legal residency, but further information would be needed to confirm this.

This is pretty impressive. But there are a few things about this explanation that give me pause.

Section 3(1)(b)(i) reads as follows:

Payment of full pension

(1) Subject to this Act and the regulations, a full monthly pension may be paid to

…

(b) every person who

(i) on July 1, 1977 was not a pensioner but had attained twenty-five years of age and resided in Canada or, if that person did not reside in Canada, had resided in Canada for any period after attaining eighteen years of age or possessed a valid immigration visa,

So paragraph 1 of the answer is dealing with that requirement. And it makes a couple of mistakes that a human wouldn’t make. First, there is no question about whether or not the person had attained twenty-five years of age as of July 1, 1977. They were born in 1950, so they would need to be at least 26 at that point. GPT has correctly identified it as a requirement, but incorrectly treated it as a requirement that hasn’t yet been met.

Second, GPT has left out the part about possessing a valid immigration visa. Presumably, that is because it has incorrectly identified that requirement as met, when it is not, because the text of 3(1)(b)(i) asks whether they were in possession of the immigration visa as of July 1, 1977, and the facts did not specify a date on which the person held the visa.

The answer also seems to completely ignore 3(1)(c), and the answer isn’t clear whether the requirements are “all of” or “any of”. That latter problem might be a result of the fact that the rules are using the word “and” disjunctively. If you qualify under any of 3(1)(a-c), you qualify.

So ChatGPT4 is impressive, but asking it to read and understand this small section of law with a partially-specified fact scenario, it makes a number of mistakes.

Legal Reasoning Automation Requires Highly Trustworthy Systems

Automating legal advice carries the risk that incorrect advice will be followed to the detriment of the user. LLMs remain unreliable in the way they read and interpret laws, in ways that are worse than the sort of unreliability inherent in having human beings do the same task.

It’s also really difficult for the LLM or anyone who is not a human expert to detect when the LLM is making a mistake, or to predict when and where it is likely to happen. Which means there is no real opportunity to mitigate the potential risks without defeating the purpose of automating in the first place.

If we are going to use automated systems to give people advice about what laws mean, that advice needs to be highly trustworthy, and LLMs just aren’t.

So yes, ChatGPT4 is significantly better than what came before. But no, it is still not appropriate to rely on ChatGPT4 on its own to provide advice about what statutes and regulations require of people.

How can GPT4 be used in Rules as Code?

Let’s assume that you have a symbolic artificial intelligence tool for Rules as Code, like Blawx aspires to be. You can use that tool to generate encodings that represent laws. Then, you can provide fact scenarios to a reasoner, and ask the reasoner to answer specific legal questions in that context, and to explain its answers with reference to the original statutory text.

The main problem with this approach is the knowledge acquisition bottleneck. Blawx is aimed at minimizing the bottleneck by making it possible for non-programmers to generate the knowledge representation. But the job still has to be done by a person who is knowledgeable about the rules, and skilled with the tool. That is a considerable expense, and a major risk factor in terms of the scalability of Rules as Code.

What would be wonderful is if we could use GPT4 to generate Blawx encodings that represent legal texts. If that was possible, we might be able to shortcut the encoding of laws, and spend more of our human labour on editing and validating those encodings.

GPT4 could also be used to create a natural language interface to the reasoner for specifying facts in the validation and use of the encoding. It could also be used to simplify the explanations that are generated from draft or validated encodings.

Let’s look at each in turn, to see how realistic it is with GPT4 compared to previous iterations:

Can ChatGPT4 be the user interface to a symbolic reasoner?

In order to use ChatGPT4 as the user interface to a symbolic reasoner like Blawx, you would need to be able to communicate to ChatGPT4 the data structure in use by the reasoner, and the data format that is used by the reasoner, then ask ChatGPT4 to interview the user and collect the facts from the user, represent them in that data structure, and express that data structure in the format expected by the reasoner.

As a brief experiment, I tried this using the new version of the JSON packages accepted by

the /interview endpoint on Blawx tests. I created a prompt that described the expected

format, and how to represent different kinds of statements in that format. I then asked

ChatGPT to collect information from me, and represent that information back to me as

a list of JSON statements.

I explained the ontology by saying the following:

The ontology for this conversation includes the category “game”, which refers to a game of Rock Paper Scissors, “player”, which refers to a person, and “sign”, which refers to a hand sign used in a game of rock paper scissors. A game has the attribute “participant”, which refers to players who participated in the game. Players have the attribute “throw”, which refers to a sign that they threw. Signs have the attribute “beats”, which refers to the signs that they defeat in pairwise competition.

This is the ontology used by the Rock Paper Scissors example included with Blawx.

I then started the interview, and gave it the following prompts:

OK. There are three signs: rock, paper, and scissors. Rock beats scissors, scissors beats paper, and paper beats rock. Jason and Bob played in a game called “testgame”. Jason threw paper and bob threw scissors.

There is another player called sally. Sally also played in testgame, but I don’t know what sign she threw.

Lizard is a sign that beats rock. Sally never throws lizard.

The final version of the JSON that ChatGPT4 generated is shown here:

{

"facts": [

{"type": "true", "category": "sign", "object": "rock"},

{"type": "true", "category": "sign", "object": "paper"},

{"type": "true", "category": "sign", "object": "scissors"},

{"type": "true", "category": "sign", "object": "lizard"},

{"type": "true", "attribute": "beats", "object": "rock", "value": "scissors"},

{"type": "true", "attribute": "beats", "object": "scissors", "value": "paper"},

{"type": "true", "attribute": "beats", "object": "paper", "value": "rock"},

{"type": "true", "attribute": "beats", "object": "lizard", "value": "rock"},

{"type": "true", "category": "player", "object": "jason"},

{"type": "true", "category": "player", "object": "bob"},

{"type": "true", "category": "player", "object": "sally"},

{"type": "true", "attribute": "throw", "object": "jason", "value": "paper"},

{"type": "true", "attribute": "throw", "object": "bob", "value": "scissors"},

{"type": "unknown", "attribute": "throw", "object": "sally", "value": "A"},

{"type": "false", "attribute": "throw", "object": "sally", "value": "lizard"},

{"type": "true", "category": "game", "object": "testgame"},

{"type": "true", "attribute": "participant", "object": "testgame", "value": "jason"},

{"type": "true", "attribute": "participant", "object": "testgame", "value": "bob"},

{"type": "true", "attribute": "participant", "object": "testgame", "value": "sally"}

]

}

As far as I can tell, that’s perfect. It correctly used variables in the place of values when a specific value wasn’t specified. It knew which statements were false, and which were expressions of uncertainty. It never invented any syntax or category or attribute names.

So can ChatGPT4 be used as a method of collecting and encoding facts provided by a user? Yes! That seems to be well within the range of its capabilities, even with an unusually complicated input data structure like the one Blawx uses.

Can GPT4 be Used to Summarize Symbolic Explanations?

Summarizing natural language is one of the things that GPT4 is very good at. The explanations that are generated by Blawx can be at times daunting to read. The reason for that is that the natural language explanations generated by Blawx are effectively a trace of all of the reasoning steps that the Blawx reasoner followed in trying to find the answer. The Blawx reasoner has no knowledge of which of those steps would be obvious or otherwise not worth sharing with a human user.

So can GPT4 take an explanation from Blawx and make it easier to read?

Well, I did a demo at DocaCon 2023 last week in which I showed an example of just this idea.

Here’s the raw text explanation that was generated by Blawx, displayed inside a Docassemble interview.

a full monthly pension may be paid to jason, because the conclusion in sec_3__subsec_1_section that a full monthly pension may be paid to jason holds, because according to sec_3__subsec_1_section, a full monthly pension may be paid to jason, because the conclusion in sec_3__subsec_1__para_a_section that jason qualifies under s3(1)(a) holds, because according to sec_3__subsec_1__para_a_section, jason qualifies under s3(1)(a), because jason is a person, and jason was a pensioner on July 1 1977 there is no evidence that the conclusion in sec_3__subsec_1_section that a full monthly pension may be paid to jason is defeated, because there is no evidence that the conclusion in sec_4__subsec_1_section that it is not the case that a full monthly pension may be paid to jason holds, because there is no evidence that according to sec_4__subsec_1_section, it is not the case that a full monthly pension may be paid to jason, because jason is a person, justified above, and jason was a pensioner on July 1 1977, justified above

I actually asked ChatGPT3.5 to summarize that text, and here’s what it generates:

Jason qualifies for a full monthly pension according to Section 3, Subsection 1, Paragraph a because he is a person and was a pensioner on July 1, 1977. There is no evidence to contradict this conclusion in Section 3, Subsection 1 or Section 4, Subsection 1. Therefore, Jason is eligible for the full monthly pension.

That is a good summary. And even if it wasn’t, the risk factors involved in using GPT to summarize explanations are much lower, because there’s nothing stopping you from giving the user access to the raw explanation, also, and advising them not to rely on the summary.

So GPT4 can certainly also be used to simplify the explanations that are generated by symbolic tools like Blawx.

Can GPT4 be Used to Generate Encodings?

This is the place where GPT4 has the greatest potential to help make Rules as Code viable going forward - if we can use it to accelerate the task of generating encodings of legal text. In a perfect future world, it would just do that work for us. But a good first step would be if GPT4 was capable of giving human drafters a good first draft to work from.

This is very much how the Codex features of GPT are being used by software developers, now, which has been very helpful to people. But unfortunately, the programming languages or platforms in which laws are most usefully encoded are not commonly used, and laws are seldom the source material for code. So the training data available to GPT4 on how to convert from laws to encodings is relatively weak compared to information on how to draft Python code, for example.

But maybe we could help it get closer.

In order to be able to test this idea with Blawx, I needed a way for GPT4 to generate Blawx code in text, in such a way that I could read and validate it. I came up with a relatively simple syntax that is built around how the blocks appear visually in blocks. Essentially, a statement is preceded with a hyphen, a value input is surrounded by angle brackets, a field input is surrounded by parenthesis, and a statement input is preceded by a colon and a newline, followed by an indented block of statements. Variables are expressed in all-caps, values and plain text elements appear normally.

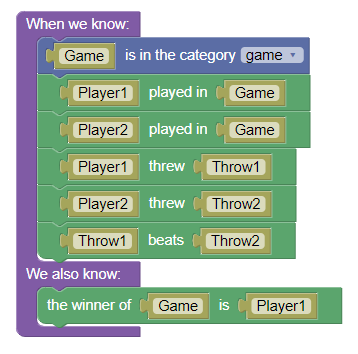

For example, this rule in Blawx:

Would appear like this in the text version:

- When we know:

- <GAME> is in the category (game)

- <PLAYER1> played in <GAME>

- <PLAYER2> played in <GAME>

- <PLAYER1> threw <THROW1>

- <PLAYER2> threw <THROW2>

- <THROW1> beats <THROW2>

We also know:

- the winner of <GAME> is <PLAYER1>

Note that in order to actually deploy this approach, we would need to make dramatic changes to the Blawx code, so that it was generating and generated by this text version, and we had a parser for the text version that would generate s(CASP) code. That would be “a lot of work"™️, and hasn’t happened yet. But we can experiment with just the text syntax and GPT4 to see if it would be worthwhile

Using that format, I was able to create a prompt for GPT4 that would give it an understanding of the format for a subset of the Blawx block language, and then give it some examples of how translations from legal text to encodings might look.

I then asked it to generate a legal encoding for a portion of the Old Age Security Act:

3.(1) Subject to this Act and the regulations, a full monthly pension may be paid to

(b) every person who

(i) on July 1, 1977 was not a pensioner but had attained twenty-five years of age and resided in Canada or, if that person did not reside in Canada, had resided in Canada for any period after attaining eighteen years of age or possessed a valid immigration visa,

Here is the code that ChatGPT4 generated in response:

- We know:

- (age) is an attribute of category (person) of type (number) described as "() object (is) value (years old)"

- (resided_in_canada) is an attribute of category (person) of type (boolean) described as "() object (resided in Canada)"

- (valid_immigration_visa) is an attribute of category (person) of type (boolean) described as "() object (possessed a valid immigration visa)"

- When we know:

- as of <1977-07-01>:

- <PERSON> is not a pensioner

- <PERSON> is <25> years old

- <PERSON> resided in Canada

We also know:

- <PERSON> is entitled to a full monthly pension

- When we know:

- as of <1977-07-01>:

- <PERSON> is not a pensioner

- <PERSON> is <25> years old

- <PERSON> did not reside in Canada

- <PERSON> resided in Canada after attaining <18> years of age

We also know:

- <PERSON> is entitled to a full monthly pension

- When we know:

- as of <1977-07-01>:

- <PERSON> is not a pensioner

- <PERSON> is <25> years old

- <PERSON> did not reside in Canada

- <PERSON> possessed a valid immigration visa

We also know:

- <PERSON> is entitled to a full monthly pension

There is a lot to like about this result. It is a drastic improvement over what you get from ChatGPT3.5 with the same prompting. It perfectly follows the syntax for the text version of Blawx code. It determines that there were ontological concepts that needed to be defined before they could be used, and did so. It succesfully used multiple rules with the same conclusion in the place of disjunction.

The code isn’t right, of course. And it’s wrong in two different ways, which are of different importance. First, it’s logically incorrect. But if ChatGPT4 was suddenly generating logically correct answer set programming code to represent laws in a language it had never seen before on the first try, that would be pretty surprising. And what we are aiming for, here, is a sufficiently good first draft that it might accellerate the drafting process. Logically incorrect is okay, in that context.

The more significant concern is if there are issues that prevent the response from being usable, and unfortunately, we have two examples of that, here, too.

First, it is inventing incorrect patterns for the negation of predicates that it defined.

For example, it uses <PERSON> is not a pensioner when it should be using

- there is no evidence that:

- <PERSON> is a pensioner

Also, it is using attributes that it did not define, like <PERSON> resided in Canada after attaining <18> years of age.

These are larger problems, because semantically incorrect code can be fixed, but syntactically incorrect code won’t even load in the Blawx reasoner. But because they seem relatively limited in scope, it might be that there are prompt engineering tricks that could be used to prevent that sort of problem. If so, we can say that ChatGPT4 is capable of creating low-quality but syntactically correct encodings of legal concepts. Even then, we don’t know if the quality of the encodings would be sufficient to speed up development.

Blawx and GPT4

It’s interesting to note that I think that Blawx is particularly well suited to being used with GPT in the above ways, for a couple of reasons.

First, Blawx already generates natural language explanations for its answers. They are verbose, and tree-structured by default, but they are natural language explanations nonetheless. That might make the output of Blockly particularly well suited to being simplified by tools like GPT4.

Second, I have designed Blawx in such a way as to impose a limited ontological structure, with natural language descriptions for each element. Using ChatGPT4 as a user interface for Blawx might require some fine-tuning of that structure, to include natural language descriptions of what each category and attribute represents. But that basic structure of a strictly pre-defined ontology with natural language components is well suited to giving instructions to GPT4 for how to collect input from the user.

Third, I have designed Blawx to be as structurally-isomorphic as possible with the original legislation. That means there is a one-to-one relationship between the smallest possible pieces of law, and corresponding pieces of code. That means that the task of translating from law to code can be broken down into the smallest reasonable pieces, which in turns makes it easier for GPT4 to do. Longer, more complex inputs and outputs increase the risk of hallucination. Plus, as you go about completing your Blawx encoding, you are essentially generating a few-shot prompt that will make GPT4 even better at following the same style in encoding the rest of the law. Non-declarative systems, and systems that can’t use default reasoning in a structurally isomorphic way, will force tools like GPT4 to consider more of the law and more of the code at the same time, and will not be able to get as much help.

Fourth, Blawx is essentially a controlled natural language. I suspect tools like GPT4 might be better at controlled natural languages than they are at more abstruse representations. But that’s pure speculation. It’s one of the many, many things I’d be interested in experimenting on.

But perhaps most important about the combination of the two is this: To the extent that GPT4 is not good enough to draft symbolic encodings, that problem can be solved by giving it more and better examples. That requires tools for human-drafted symbolic encodings of laws. To the extent that GPT4 is capable of generating those encodings, they need to be validated by human beings before they would be trustworthy. Which means GPT4 needs to generate code that can be used in tools for human-edited and human-validated symbolic encodings. Which are the precise same tools. Either way, to be useful for law, statistical AI like GPT4 needs symbolic AI like Blawx.

Conclusion

GPT4 is not enough, on its own, to build trustworthy legal automation. It is too prone to logical error in understanding the meaning of legal texts. However, while GPT3.5 was capable of summarizing explanations generated by symbolic encodings, GPT4 has enhanced capabilities for acting as an expert system style front end, even with advanced representation styles. Unlike GPT3.5, GPT4 is very close to being able to generate syntactically valid (if semantically weak) Blawx encodings on the basis legal text. If the remaining syntactical hurdles could be leapt, we might find that the ability of GPT4 to do a “first draft” of an encoding is a major reduction in effort required for generating Rules as Code encodings in the future.

On the other hand, we might also find that extending the text version of the Blawx language to cover more of its features, and giving GPT4 sufficient examples to be able to use them all, stretches the limits of the inputs that GPT4 can reasonably handle. Or we might find that the semantic weakness in the generated code is so severe, or otherwise challenging to detect and fix, that the automatically-generated code is not yet a net gain for efficiency.

Both improving the capability of tools like GPT to generate semantically accurate encodings of laws, and validating those encodings once they exist, requires tools like Blawx to be successful.

It’s not GPT or Blawx, it’s GPT and Blawx.

Upcoming

Tomorrow, April 13, 2023, I’m going to attend the FutureLaw conference at CodeX, Stanford Law’s centre for Computational Law. If you’re there, feel free to find me on the zoom chat.